At American Family Ventures, we believe “Insurance 2.0.” will be, in part, shaped by structural innovation. The traditional insurance structure of centralized risk-pooling has been around for a long time. Unsurprisingly, it is also subject to heavy regulation. As a result, many entrepreneurs are using new approaches to lower regulatory burdens or unlock value through decentralization.

Two of the approaches we’re excited to watch develop are peer-to-peer (P2P) and private-investor-backed insurance.

Peer-to-Peer Insurance

P2P insurance isn’t a new concept. Mutual insurance companies effectively use a peer-to-peer model today. However, there appear to be a number of emerging approaches altering the dynamics of the risk/insured pool and creating new benefits for policyholders, carriers and investors.

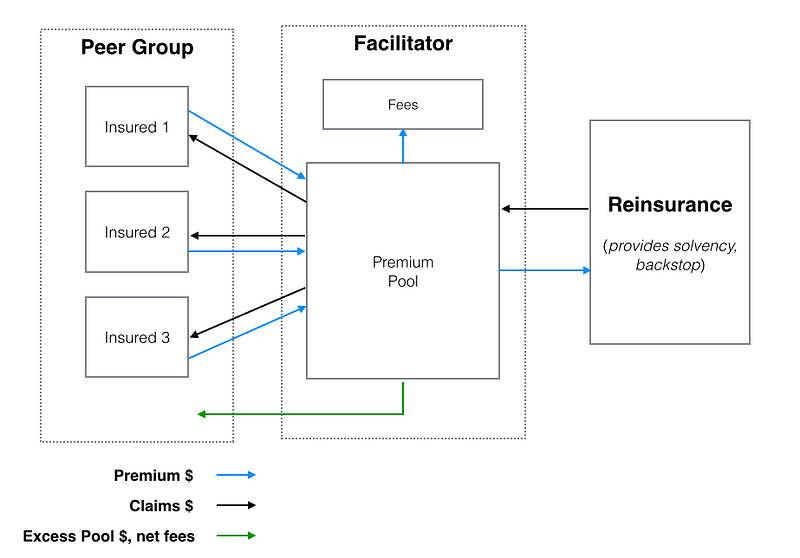

For context, we see P2P as a set of techniques allowing insureds to self-organize, self-administer and pool their capital in a way that protects all the pool members from loss, all while ensuring any capital in the pool not reserved to pay claims (less any fees owed to a facilitator or administrator) is returned directly to the pool members. Of course, there is a great deal of nuance to making that work.

See Also: P2P Start-Ups From Around the World

Here’s a simplified diagram of a P2P insurance model:

We’ve identified a few reasons to think that, by redefining the traditional insurance structure, P2P models can offer unique benefits.

For one, the P2P system could mitigate elements of conflict in traditional, centralized insurance models. Because insurers (for the most part) get to keep the premiums they don’t pay out in claims, occasionally the incentives of policyholders and carriers fall out of alignment. Conversely, in a pure P2P model, because the premiums not needed for claims are refunded to the policyholders, in theory, any conflict with a carrier is diminished.

While that logic is clear, it likely oversimplifies the issue. The insurance system, while not without its flaws, has functioned for some time and has regulations and processes in place to mitigate adversarial circumstances. In addition, if conflict exists in the insurer/insured relationship, it likely remains present in the P2P model but shifts from customer/carrier to peer/peer. In essence, because any pool member’s payout is a function of the claims paid out to others in the pool, members now have personal disincentives to pay claims, similar to carriers in the traditional model. That said, the carrier/customer relationship isn’t perfect, and new variations of P2P could help advance it.

Secondly, P2P organizing models might leverage large networks like Facebook and LinkedIn more effectively than traditional insurance. The nature of self-selection logically fits the use of a social or professional network — it’s easier to imagine a group of Facebook friends deciding to form an “insurance group” than it is to imagine that same group recommending all of their friends purchase individual policies from a large provider. In effect, large networks power the formation of smaller networks.

In addition to organizing benefits, integration with large, network-based platforms can create efficiencies in administration and retention. Increased frequency of engagement as well as preexisting communication and payment infrastructure could power usability advantages, stronger net promoter scores and better retention rates.

Finally, P2P models, by enabling modifications to the size and composition of risk pools, could create differentiated pricing strategies. P2P models are often associated with self-organization, but they don’t necessarily require it. So, if P2P facilitators become involved in pool selection and can use existing or new underwriting criteria to influence or control pool composition, they could construct pools that offer each member the highest possible returns after claims (or, effectively, the lowest possible cost of insurance). In other words, P2P facilitators might algorithmically generate smaller baskets of varying risk profiles, shifting members, when necessary, to intentionally spread expected claims across numerous pools, thereby creating consistently lower average claims volumes per pool (and, consequently, better payouts for members).

Private-Investor-Backed Insurance

Private-investor-backed insurance allows third-party investment capital to pay or backstop claims expenses in exchange for investment return. For example, a private investor, in theory, could agree to receive premium payments from a basket of insureds in exchange for the obligation to pay claims when they arise. In this model, the private investor (or group of private investors) essentially steps into the financial shoes of the insurer, accepting a stream of certain cash flows in exchange for an uncertain future liability (which could exceed those cash flows). The facilitator of such a marketplace would likely take some fees in exchange for customer acquisition, administration, securing reinsurance and performing the functions of an insurer other than providing risk capital.

See Also: Insurance 2.0: How Distribution Evolves

There are a handful of benefits we think the private-investor-backed model offers participants in the insurance relationship.

First, if certain types of insurance risk can be effectively securitized, those securities would (theoretically) offer professional or retail investors diversification through an instrument that is not highly correlated with the general market (low beta). Some investors already have exposure to insurance through reinsurance contracts and catastrophe bonds, but securitized insurance could offer broader access to more familiar risks with different payoff profiles.

Secondly, similar to what Lending Club and Prosper were able to accomplish in personal and small business lending, a private-investor-backed insurance model might offer price-competitive options to customers who have difficulty securing traditional insurance. For example, today, customers who are unable to secure insurance from conventional insurers (standard market) use excess and surplus (E&S) markets to address their insurance needs. If private investors are willing to take on these E&S risks—whether due to the presence of unique underwriting criteria or higher risk appetites—they could create new competitive dynamics in the E&S market and ultimately improve options for buyers.

As a side note, we often hear people combining the notions of P2P and private-investor-backed insurance. In our minds, they are related and can work together but are separate concepts. Private investor backing is not a prerequisite to building a P2P model — a pure P2P model could employ a variety of strategies to guarantee liquidity and solvency. For example, P2P insurers could leverage reinsurance to cover large or aggregate claims beyond the pool balance, eliminating the need for private investment capital. The P2P insurers might also use traditional fronting arrangements to ensure solvency. By comparison, a pure private-investor-backed model doesn’t need P2P features to function. Instead, it might offer investors financial products that look similar to reinsurance contracts without making any changes to risk pooling or centralization of control.

Additional Considerations and Questions

There are various other structural approaches that might be used to create acquisition cost and pricing advantages or lower barriers to entry for start-ups. Often, these are not necessarily new structural ideas but are rather applications of existing legal strategies employed in surplus or specialty lines insurance to broader, bigger lines.

The successful execution of the P2P model relies on a number of assumptions we’re sure someone will figure out, but we don’t fully understand them just yet. For example, will pools self-select, or will they need to be automatically or algorithmically selected? If self-selected, will most pools (financially) perform as expected, or will there be a small subset of high-performance pools (created by information asymmetry) that generate an inverse adverse selection issue for the P2P business, thereby creating disincentives for participation by the majority of potential buyers? Will pools self-administer and self-police to influence lower losses and guarantee payment of claims, or will some centralized entity still need to exist to ensure member compliance? Will there be regulatory hurdles to overcome if small pools are constructed to reduce claims costs? Finally, how will pool facilitators/administrators/members handle float management — will the capital in the pools sit in cash, or will those assets be actively managed until need for claims? If actively managed, by whom?

The issues we’re interested to see addressed in private-investor-backed insurance are also numerous. Can insurance be a desirable or profitable asset class for private investors? Apart from catastrophe bonds, we haven’t seen much securitization of insurance. Which insurance products or coverages might one securitize best? In other words, which magnitudes and patterns of risk exposures will private investors accept, which existing or new data will they demand as third-party underwriters and what terms will be up for negotiation? Can facilitators find a way to make long-tail risk compatible with liquidity expectations for the asset class?

At the end of the day, we’re looking forward to finding out how companies are able to use structural innovation to create unique and differentiated value for customers.