Work gives us an identity. So disability programs that force people to say home until they are fully recovered can create unintended problems.

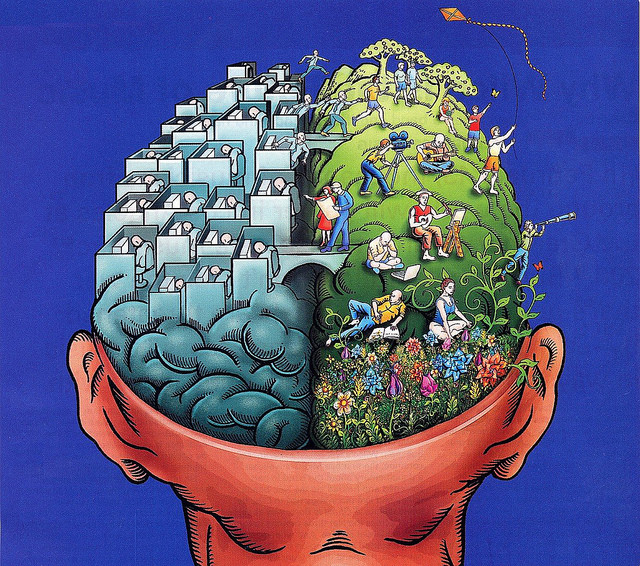

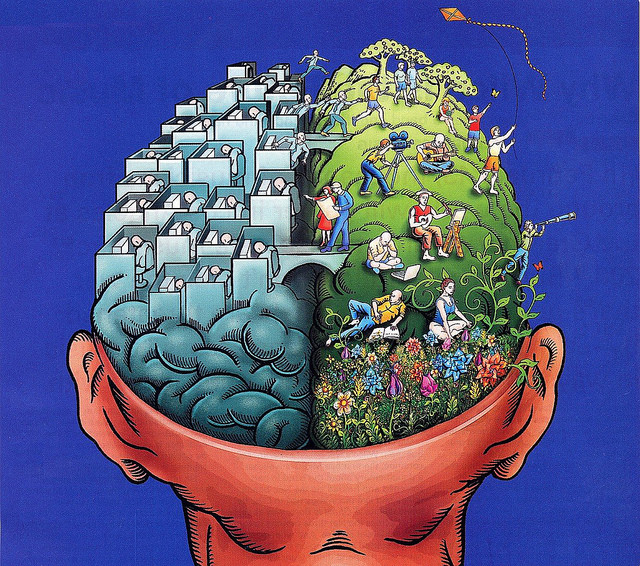

The human brain thrives on what work gives us: activity, routine, social contact and identity.

The act of working gives employees far more than just the benefit of earned income. The World Health Organization names it as a health factor that, when present, contributes to health and, when absent, can increase the chances of ill health. This is particularly relevant in the discussion about mental health. What is it about work that contributes to mental health, and why should employers and insurers consider the health benefits of work?

Activity

When human beings are engaged in doing things, areas of the brain related to attentiveness are stimulated. When someone is off work, it is harder to find regular daily activity—it is not as easy to find the many everyday behaviors we do when we are working. Work provides a structure that tells us what to do. We then engage in hundreds of behaviors every day. Being in the act of doing these behaviors keeps us healthy. When we are not working, it can be hard to answer the question: “So what did you do today?” This absence of activity can have a profound impact on a person’s sense of accomplishment and purpose, which has an impact on mental health.

Routine

Work forces us into a rhythm and regular behavioral patterns that are actually good for us, even if sometimes we may resent the structure. Our bodies and brains enjoy the routine and benefit from the repeated predictable patterns of behavior. If we don’t have something to get out of bed for, it can be difficult to get out of bed. When someone is off work for any reason, the lack of daily direction can have a significant impact on well-being.

Social contact

We spend more waking hours with the people we work with (when we are working full-time hours) than with the people we love and live with. Human beings as mammals are social creatures and seek and thrive on social contact. Neural activity related to social contact is crucial to mental health, and social isolation is a risk factor for mental illness. We are connected to our co-workers because we are social beings who are genetically programmed to monitor and build social connections. We rely on the hundreds of exchanges inside the social context at work to meet our needs for belonging and connection. When people are off work, they lose this continuing social contact, and the isolation has a significant impact on well-being.

Identity

Work gives us identity. When we work we have a title, a position, a clearly defined set of tasks and a label that provides information to the world about who we are, this informs us about who we are in relation to others, and in how we view ourselves. Loss of this identifier has a significant negative impact on self-esteem and self-worth, with a predictable risk to mental health. When employees are off work, it is hard for them to answer the common question: “So, what do you do?”

Any person facing unemployment experiences changes in all of these factors and is at risk for developing mental health issues. A person who already is experiencing mental health challenges, and then goes off work, may find it difficult to build steady recovery, because the essential health need of work is not present.

Many disability plans have an all-or-nothing approach to an employee’s ability to work. If employees are off work, they are deemed not able to work. If employees wish to find regular daily activity to help build their recovery, they may put their claim at risk. This approach to disability management may actually be making employees stay off work longer. The longer an employee is off work, the harder it is to return to work. Systems that do not allow employees who are on a disability claim to work, even to perform volunteer work, are preventing employees from tapping into the health benefits of working and may be contributing to needless work disability.

Employers may also have the mindset that an employee who is sick should be off work. When it comes to mental health issues, it is not best practice to use this all-or-nothing approach. The key here is for employers to have the capacity to address individual employee needs as they return to work or, better yet, have flexible processes and structures that allow employees to stay at work. Staying at work during early days of recovery could be part-time, with the disability benefit covering the balance of an employee’s income from salary.

Continuing activity, routine, social contact and identity build employee recovery and can reduce the cost of the disability claim. There is less work disruption, and continuity can be maintained for the employee and the family, the work team and the organization. This contributes to increased employee health. And healthy employees are productive and engaged employees.