I Block, Therefore I Chain? What is, and what isn’t, a "blockchain"? The Bitcoin cryptocurrency uses a data structure that I have often termed as part of a class of "mutual distributed ledgers." Let me set out the terms as I understand them:

- ledger – a record of transactions;

- distributed – divided among several or many, in multiple locations;

- mutual – shared in common, or owned by a community;

- mutual distributed ledger (MDL) – a record of transactions shared in common and stored in multiple locations;

- mutual distributed ledger technology – a technology that provides an immutable record of transactions shared in common and stored in multiple locations.

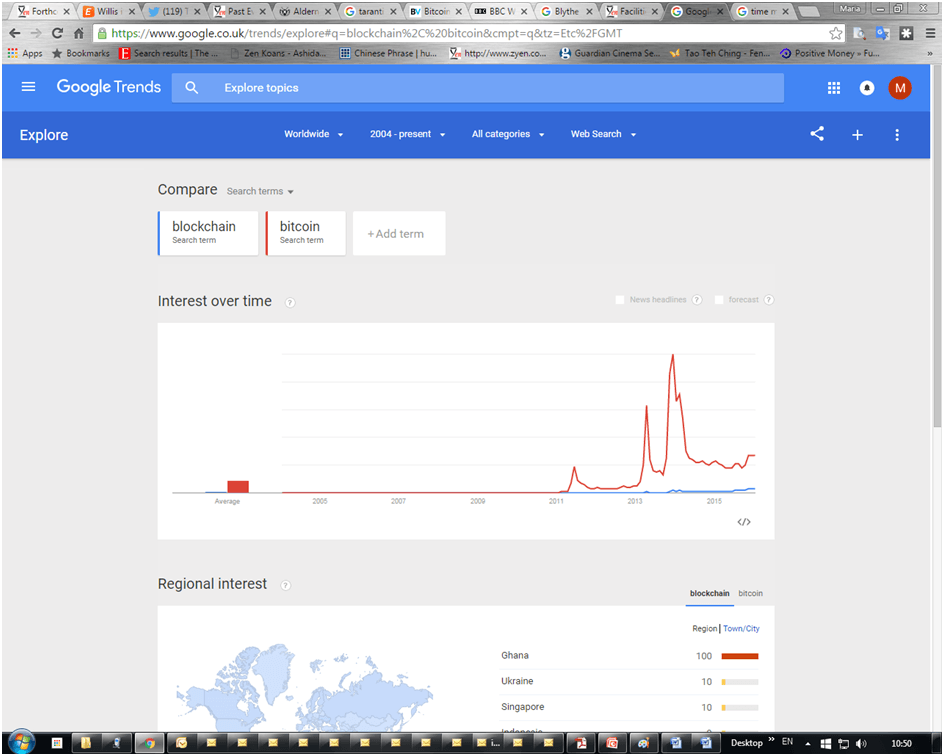

Interestingly, the 2008 Satoshi Nakamoto paper that preceded the Jan. 1, 2009, launch of the Bitcoin protocol does not use the term "blockchain" or "block chain." It does refer to "blocks." It does refer to "chains." It does refer to "blocks" being "chained" and also a "proof-of-work chain." The paper’s conclusion echoes a MDL – “we proposed a peer-to-peer network using proof-of-work to record a public history of transactions that quickly becomes computationally impractical for an attacker to change if honest nodes control a majority of CPU power.” [Satoshi Nakamoto, Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System, bitcoin.org (2008)] I have been unable to find the person who coined the term "block chain" or "blockchain." [Contributions welcome!] The term "blockchain" only makes it into Google Trends in March 2012, more than three years from the launch of the Bitcoin protocol.  And the tide may be turning. In July 2015, the States of Jersey issued a consultation document on regulation of virtual currencies and referred to "distributed ledger technology." In January 2016, the U.K. Government Office of Science fixed on "distributed ledger technology," as does the Financial Conduct Authority and the Bank of England. Etymological evolution is not over. Ledger Challenge Wuz we first? Back in 1995, our firm, Z/Yen, faced a technical problem. We were building a highly secure case management system that would be used in the field by case officers on personal computers. Case officers would enter confidential details on the development and progress of their work. We needed to run a large concurrent database over numerous machines. We could not count on case officers out on the road dialing in or using Internet connections. Given the highly sensitive nature of the cases, security was paramount, and we couldn’t even trust the case officers overly much, so a full audit trail was required. We took advantage of our clients’ "four eyes" policy. Case officers worked on all cases together with someone else, and not on all cases with the same person. Case officers had to jointly agree on a final version of a case file. We could count on them (mostly) running into sufficient other case officers over a reasonable period and using their encounters to transmit data on all cases. So we built a decentralized system where every computer had a copy of everything, but encrypted so case officers could only view their own work, oblivious to the many other records on their machines. When case officers met each other, their machines would "openly" swap their joint files over a cable or floppy disk but "confidentially" swap everyone else’s encrypted files behind the scenes, too. Even back at headquarters, four servers treated each other as peers rather than having a master central database. If a case officer failed to "bump into" enough people, then he or she would be called and asked to dial in or meet someone or drop by headquarters to synchronize. This was, in practice, rarely required. We called these decentralized chains "data stacks." We encrypted all of the files on the machines, permitting case officers to share keys only for their shared cases. We encrypted a hash of every record within each subsequent record, a process we called "sleeving." We wound up with a highly successful system that had a continuous chain of sequentially encrypted records across multiple machines treating each other as peers. We had some problems with synchronizing a concurrent database, but they were surmounted. Around the time of our work, there were other attempts to do similar highly secure distributed transaction databases, e.g. Ian Griggs and Ricardo on payments, Stanford University and LOCKSS and CLOCKSS for academic archiving. Some people might point out that we weren’t probably truly peer-to-peer, reserving that accolade for Gnutella in 2000. Whatever. We may have been bright, perhaps even first, but were not alone. Good or Bad Databases? In a strict sense, MDLs are bad databases. They wastefully store information about every single alteration or addition and never delete. In another sense, MDLs are great databases. In a world of connectivity and cheap storage, it can be a good engineering choice to record everything "forever." MDLs make great central databases, logically central but physically distributed. This means that they eliminate a lot of messaging. Rather than sending you a file to edit, which you edit, sending back a copy to me, then sending a further copy on to someone else for more processing, all of us can access a central copy with a full audit trail of all changes. The more people involved in the messaging, the more mutual the participation, the more efficient this approach becomes. Trillions of Choices Perhaps the most significant announcement of 2015 was in January from IBM and Samsung. They announced their intention to work together on mutual distributed ledgers (aka blockchain technology) for the Internet-of Things. ADEPT (Autonomous Decentralized Peer-to-Peer Telemetry) is a jointly developed system for distributed networks of devices. In summer 2015, a North American energy insurer raised an interesting problem with us. It was looking at insuring U.S. energy companies about to offer reduced electricity rates to clients that allowed them to turn appliances on and off -- for example, a freezer. Now, freezers in America can hold substantial and valuable quantities of foodstuffs, often several thousand dollars. Obviously, the insurer was worried about correctly pricing a policy for the electricity firm in case there was some enormous cyber-attack or network disturbance. Imagine coming home to find your freezer off and several thousands of dollars of thawed mush inside. You ring your home and contents insurer, which notes that you have one of those new-fangled electricity contracts: The fault probably lies with the electricity company; go claim from them. You ring the electricity company. In a fit of customer service, the company denies having anything to do with turning off your freezer; if anything, it was probably the freezer manufacturer that is at fault. The freezer manufacturer knows for a fact that there is nothing wrong except that you and the electricity company must have installed things improperly. Of course, the other parties think, you may not be all you seem to be. Perhaps you unplugged the freezer to vacuum your house and forgot to reconnect things. Perhaps you were a bit tight on funds and thought you could turn your frozen food into "liquid assets." I believe IBM and Samsung foresee, correctly, 10 billion people with hundreds of ledgers each, a trillion distributed ledgers. My freezer-electricity-control-ledger, my entertainment system, home security system, heating-and-cooling systems, telephone, autonomous automobile, local area network, etc. In the future, machines will make decisions and send buy-and-sell signals to each other that have large financial consequences. Somewhat coyly, we pointed out to our North American insurer that it should perhaps be telling the electricity company which freezers to shut off first, starting with the ones with low-value contents. A trillion or so ledgers will not run through a single one. The idea behind cryptocurrencies is "permissionless" participation -- any of the billions of people on the planet can participate. Another way of looking at this is that all of the billions of people on the planet are "permissioned" to participate in the Bitcoin protocol for payments. The problem is that they will not be continuous participants. They will dip in and out. Some obvious implementation choices are: public vs. private? Is reading the ledger open to all or just to defined members of a limited community? Permissioned vs. permissionless? Are only people with permission allowed to add transactions, or can anyone attempt to add a transaction? True peer-to-peer or merely decentralized? Are all nodes equal and performing the same tasks, or do some nodes have more power and additional tasks? People also need to decide if they want to use an existing ledger service (e.g. Bitcoin, Ethereum, Ripple), copy a ledger off-the-shelf, or build their own. Building your own is not easy, but it’s not impossible. People have enough trouble implementing a single database, so a welter of distributed databases is more complex, sure. However, if my firm can implement a couple of hundred with numerous variations, then it is not impossible for others. The Coin Is Not the Chain Another sticking point of terminology is adding transactions. There are numerous validation mechanisms for authorizing new transactions, e.g. proof-of-work, proof-of-stake, consensus or identity mechanisms. I divide these into "proof-of-work," i.e. "mining," and consider all others various forms of "voting" to agree. Sometimes, one person has all the votes. Sometimes, a group does. Sometimes, more complicated voting structures are built to reflect the power and economic environment in which the MDL operates. As Stalin said, “I consider it completely unimportant who in the party will vote, or how; but what is extraordinarily important is this — who will count the votes, and how.” As the various definitions above show, the blockchain is the data structure, the mechanism for recording transactions, not the mechanism for authorizing new transactions. So the taxonomy starts with an MDL or shared ledger; one kind of MDL is a permissionless shared ledger, and one form of permissionless shared ledger is a blockchain. Last year, Z/Yen created a timestamping service, MetroGnomo, with the States of Alderney. We used a mutual distributed ledger technology, i.e. a technology that provides an immutable record of transactions shared in common and stored in multiple locations. However, we did not use "mining" to authorize new transactions. Because the incentive to cheat appears irrelevant here, we used an approach called "agnostic woven" broadcasting from "transmitters" to "receivers" -- to paraphrase Douglas Hofstadter, we created an Eternal Golden Braid. So is MetroGnomo based on a blockchain? I say that MetroGnomo uses a MDL, part of a wider family that includes the Bitcoin blockchain along with others that claim use technologies similar to the Bitcoin blockchain. I believe that the mechanism for adding new transactions is novel (probably). For me, it is a moot point if we "block" a group of transactions or write them out singly (blocksize = 1). Yes, I struggle with "blockchain." When people talk to me about blockchain, it’s as if they’re trying to talk about databases yet keep referring to “The Ingres” or “The Oracle.” They presume the technological solution, “I think I need an Oracle” (sic), before specifying the generic technology, “I think I need a database.” Yet I also struggle with MDL. It may be strictly correct, but it is long and boring. Blockchain, or even "chains" or "ChainZ" is cuter. We have tested alternative terms such as “replicated authoritative immutable ledger,” “persistent, pervasive,and permanent ledger” and even the louche “consensual ledger.” My favorite might be ChainLedgers. Or Distributed ChainLedgers. Or LedgerChains. Who cares about strict correctness? Let’s try to work harder on a common term. All suggestions welcome!

And the tide may be turning. In July 2015, the States of Jersey issued a consultation document on regulation of virtual currencies and referred to "distributed ledger technology." In January 2016, the U.K. Government Office of Science fixed on "distributed ledger technology," as does the Financial Conduct Authority and the Bank of England. Etymological evolution is not over. Ledger Challenge Wuz we first? Back in 1995, our firm, Z/Yen, faced a technical problem. We were building a highly secure case management system that would be used in the field by case officers on personal computers. Case officers would enter confidential details on the development and progress of their work. We needed to run a large concurrent database over numerous machines. We could not count on case officers out on the road dialing in or using Internet connections. Given the highly sensitive nature of the cases, security was paramount, and we couldn’t even trust the case officers overly much, so a full audit trail was required. We took advantage of our clients’ "four eyes" policy. Case officers worked on all cases together with someone else, and not on all cases with the same person. Case officers had to jointly agree on a final version of a case file. We could count on them (mostly) running into sufficient other case officers over a reasonable period and using their encounters to transmit data on all cases. So we built a decentralized system where every computer had a copy of everything, but encrypted so case officers could only view their own work, oblivious to the many other records on their machines. When case officers met each other, their machines would "openly" swap their joint files over a cable or floppy disk but "confidentially" swap everyone else’s encrypted files behind the scenes, too. Even back at headquarters, four servers treated each other as peers rather than having a master central database. If a case officer failed to "bump into" enough people, then he or she would be called and asked to dial in or meet someone or drop by headquarters to synchronize. This was, in practice, rarely required. We called these decentralized chains "data stacks." We encrypted all of the files on the machines, permitting case officers to share keys only for their shared cases. We encrypted a hash of every record within each subsequent record, a process we called "sleeving." We wound up with a highly successful system that had a continuous chain of sequentially encrypted records across multiple machines treating each other as peers. We had some problems with synchronizing a concurrent database, but they were surmounted. Around the time of our work, there were other attempts to do similar highly secure distributed transaction databases, e.g. Ian Griggs and Ricardo on payments, Stanford University and LOCKSS and CLOCKSS for academic archiving. Some people might point out that we weren’t probably truly peer-to-peer, reserving that accolade for Gnutella in 2000. Whatever. We may have been bright, perhaps even first, but were not alone. Good or Bad Databases? In a strict sense, MDLs are bad databases. They wastefully store information about every single alteration or addition and never delete. In another sense, MDLs are great databases. In a world of connectivity and cheap storage, it can be a good engineering choice to record everything "forever." MDLs make great central databases, logically central but physically distributed. This means that they eliminate a lot of messaging. Rather than sending you a file to edit, which you edit, sending back a copy to me, then sending a further copy on to someone else for more processing, all of us can access a central copy with a full audit trail of all changes. The more people involved in the messaging, the more mutual the participation, the more efficient this approach becomes. Trillions of Choices Perhaps the most significant announcement of 2015 was in January from IBM and Samsung. They announced their intention to work together on mutual distributed ledgers (aka blockchain technology) for the Internet-of Things. ADEPT (Autonomous Decentralized Peer-to-Peer Telemetry) is a jointly developed system for distributed networks of devices. In summer 2015, a North American energy insurer raised an interesting problem with us. It was looking at insuring U.S. energy companies about to offer reduced electricity rates to clients that allowed them to turn appliances on and off -- for example, a freezer. Now, freezers in America can hold substantial and valuable quantities of foodstuffs, often several thousand dollars. Obviously, the insurer was worried about correctly pricing a policy for the electricity firm in case there was some enormous cyber-attack or network disturbance. Imagine coming home to find your freezer off and several thousands of dollars of thawed mush inside. You ring your home and contents insurer, which notes that you have one of those new-fangled electricity contracts: The fault probably lies with the electricity company; go claim from them. You ring the electricity company. In a fit of customer service, the company denies having anything to do with turning off your freezer; if anything, it was probably the freezer manufacturer that is at fault. The freezer manufacturer knows for a fact that there is nothing wrong except that you and the electricity company must have installed things improperly. Of course, the other parties think, you may not be all you seem to be. Perhaps you unplugged the freezer to vacuum your house and forgot to reconnect things. Perhaps you were a bit tight on funds and thought you could turn your frozen food into "liquid assets." I believe IBM and Samsung foresee, correctly, 10 billion people with hundreds of ledgers each, a trillion distributed ledgers. My freezer-electricity-control-ledger, my entertainment system, home security system, heating-and-cooling systems, telephone, autonomous automobile, local area network, etc. In the future, machines will make decisions and send buy-and-sell signals to each other that have large financial consequences. Somewhat coyly, we pointed out to our North American insurer that it should perhaps be telling the electricity company which freezers to shut off first, starting with the ones with low-value contents. A trillion or so ledgers will not run through a single one. The idea behind cryptocurrencies is "permissionless" participation -- any of the billions of people on the planet can participate. Another way of looking at this is that all of the billions of people on the planet are "permissioned" to participate in the Bitcoin protocol for payments. The problem is that they will not be continuous participants. They will dip in and out. Some obvious implementation choices are: public vs. private? Is reading the ledger open to all or just to defined members of a limited community? Permissioned vs. permissionless? Are only people with permission allowed to add transactions, or can anyone attempt to add a transaction? True peer-to-peer or merely decentralized? Are all nodes equal and performing the same tasks, or do some nodes have more power and additional tasks? People also need to decide if they want to use an existing ledger service (e.g. Bitcoin, Ethereum, Ripple), copy a ledger off-the-shelf, or build their own. Building your own is not easy, but it’s not impossible. People have enough trouble implementing a single database, so a welter of distributed databases is more complex, sure. However, if my firm can implement a couple of hundred with numerous variations, then it is not impossible for others. The Coin Is Not the Chain Another sticking point of terminology is adding transactions. There are numerous validation mechanisms for authorizing new transactions, e.g. proof-of-work, proof-of-stake, consensus or identity mechanisms. I divide these into "proof-of-work," i.e. "mining," and consider all others various forms of "voting" to agree. Sometimes, one person has all the votes. Sometimes, a group does. Sometimes, more complicated voting structures are built to reflect the power and economic environment in which the MDL operates. As Stalin said, “I consider it completely unimportant who in the party will vote, or how; but what is extraordinarily important is this — who will count the votes, and how.” As the various definitions above show, the blockchain is the data structure, the mechanism for recording transactions, not the mechanism for authorizing new transactions. So the taxonomy starts with an MDL or shared ledger; one kind of MDL is a permissionless shared ledger, and one form of permissionless shared ledger is a blockchain. Last year, Z/Yen created a timestamping service, MetroGnomo, with the States of Alderney. We used a mutual distributed ledger technology, i.e. a technology that provides an immutable record of transactions shared in common and stored in multiple locations. However, we did not use "mining" to authorize new transactions. Because the incentive to cheat appears irrelevant here, we used an approach called "agnostic woven" broadcasting from "transmitters" to "receivers" -- to paraphrase Douglas Hofstadter, we created an Eternal Golden Braid. So is MetroGnomo based on a blockchain? I say that MetroGnomo uses a MDL, part of a wider family that includes the Bitcoin blockchain along with others that claim use technologies similar to the Bitcoin blockchain. I believe that the mechanism for adding new transactions is novel (probably). For me, it is a moot point if we "block" a group of transactions or write them out singly (blocksize = 1). Yes, I struggle with "blockchain." When people talk to me about blockchain, it’s as if they’re trying to talk about databases yet keep referring to “The Ingres” or “The Oracle.” They presume the technological solution, “I think I need an Oracle” (sic), before specifying the generic technology, “I think I need a database.” Yet I also struggle with MDL. It may be strictly correct, but it is long and boring. Blockchain, or even "chains" or "ChainZ" is cuter. We have tested alternative terms such as “replicated authoritative immutable ledger,” “persistent, pervasive,and permanent ledger” and even the louche “consensual ledger.” My favorite might be ChainLedgers. Or Distributed ChainLedgers. Or LedgerChains. Who cares about strict correctness? Let’s try to work harder on a common term. All suggestions welcome!