Recently, Munich Re announced its plan

to step into the U.S. inland flood market to offer a competitive flood coverage endorsement for participating carriers. This is the

second notable entry of international capital into an arena dominated by the federal government.

Munich Re is known as a conservative giant of international reinsurance, so it might seem odd that it is joining the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) in covering U.S. flood. A quick look at the opportunity shows why the plan makes sense.

U.S. inland flood insurance is an untapped source of non-correlated premium unlike any other in the world. The market is dominated by an incumbent market maker that is in trouble because it offers an inferior product that cannot price risk correctly (

this paper nicely summarizes the problems at NFIP). So, here is what the new entrants are seeing:

- Contrary to industry beliefs, flood is insurable. The tools are present to accurately segment risk.

- Carriers offering flood capacity will differentiate themselves from competitors. This will give them a leg up on the competition in a market that is highly homogeneous. Carriers not offering flood will likely disappear.

- The market is massive, with potentially 130 million homes and tens of billions of dollars at stake.

Let’s go into details.

Capital Into a Ripe Market

The U.S. Flood Market

As most readers of Insurance Thought Leadership already know, many carriers have flood on the drawing board right now. The Munich Re announcement was not really a surprise. We all know there will be more announcements coming soon.

Let’s summarize the market reasons for the groundswell of private insurance in U.S. flood.

The most obvious characteristic of the market is the size. For the sake of this post, we’ll just consider homes and homeowner policies. Whether one considers the number of NFIP policies in force as the market size (

about 5.4 million policies in 2014), the number of insurable buildings (133 million homes) or something in between, there is clearly a big market. And the NFIP presents itself as the ideal competitor – big, with a mandate not necessarily compatible with business results.

So, there is no doubt that a market exists. Can it be served? Yes, because the risk can be rated and segmented.

Low-Risk Flood Hazard

To be clear: A low-risk-flood property has a profile with losses estimated to be low-frequency and low-severity. In other words: Expected flood events would rarely happen, and not cause much damage if they do. For many readers, joining the words “low-risk” and “flood” together is an oxymoron. We strongly disagree. Common sense and technology can both illustrate how flood risk can be segmented efficiently and effectively into risk categories that include “low.”

Let’s start with common sense. Flood loss occurs because of three possible types of flood: coastal surge, fluvial/river or rain-induced/pluvial (

here is more information on the three types of flood). The vast majority of U.S. homeowners are not close enough to coastal or river flooding to have a loss exposure (

here is a blog post that explores the distribution of NFIP policies). Thus, the majority of American homeowners are only exposed to excess surface water getting into the home. We’d be willing to wager that most of the ITL readership does not purchase flood insurance, simply because they don’t need it. That is the common-sense way of thinking of low-risk flood exposure.

How does the technology handle this?

There is software available now that can be used to identify low-risk flood locations (as defined by each carrier), supported by the necessary geospatial data and analytics. Historically, this was not the case, but advances in remote sensing and computing capacity (as we explored

here) make it entirely reasonable now, with location-based flood risk assessment the norm in several European countries. Distance to water, elevations, localized topographical analyses and flood models can all be used to assess flood risk with a high degree of confidence. In fact, claims are now best used as a

handy ingredient in a flood score rather than as a prime indicator of flood risk.

How to Deliver Flood Insurance in the U.S.

Deliver Flood Insurance to What Kind of Market?

Readers must be wondering at the size of market, because we offered two distinctly different possibilities above – is it about 5 million to 10 million possible policies, or 130 million policies? The difference is huge – the difference is between a niche market and a mass market.

The approach taken by flood insurers thus far is for a niche market. The current approach probably has long-term viability in high-risk flood, and the early movers that are now underwriting there are establishing solid market shares, cherry-picking from the NFIP portfolio.

On a large scale, though, the insurance industry’s approach needs to be for a mass market.

Here is a case study describing the mass market opportunity:

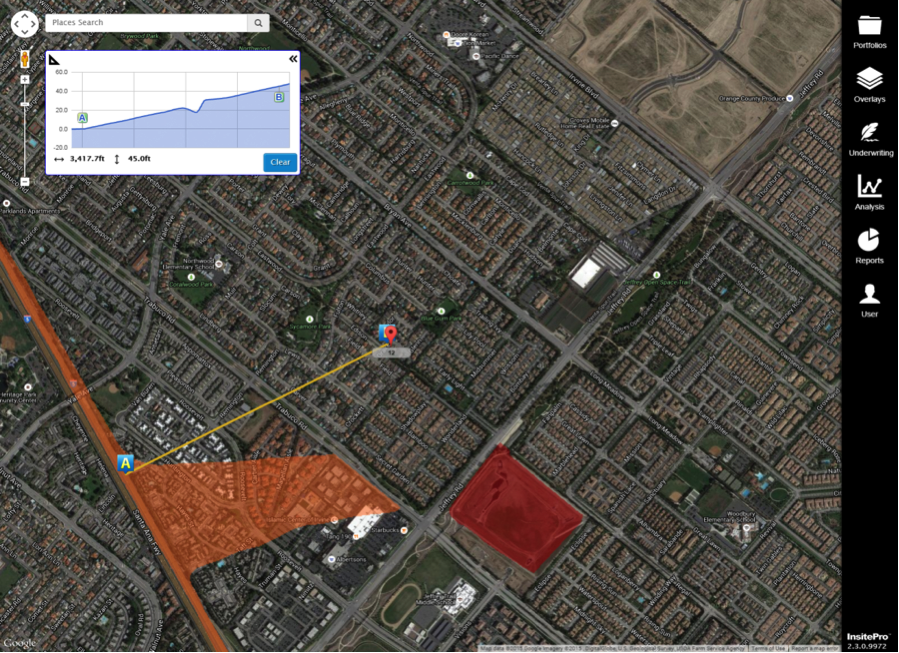

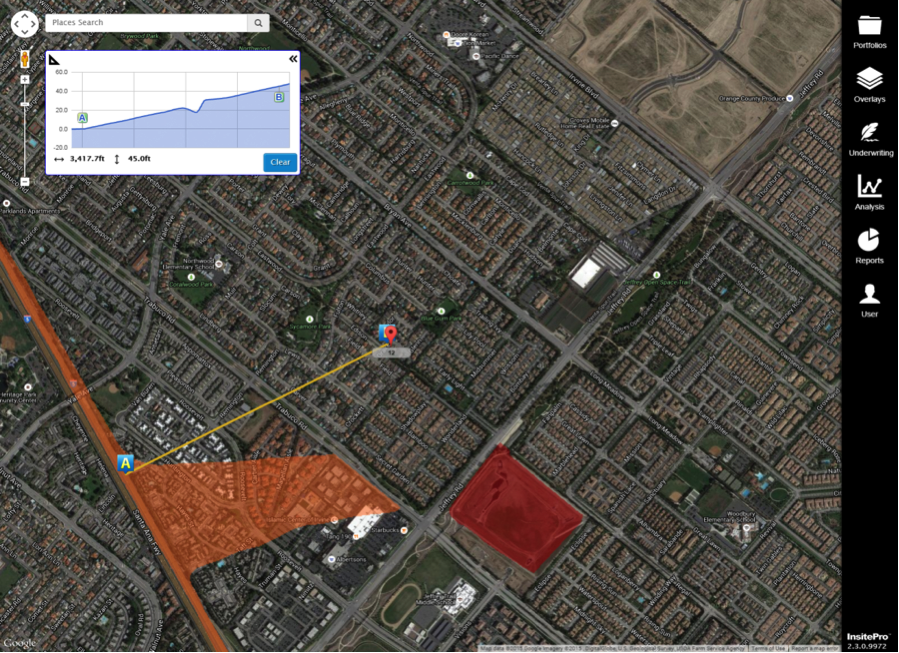

- The property is in Orange County, CA, where the climate is temperate and dry, almost borderline desert. El Niño might be coming, but that risk can be built in.

- Using InsitePro (see image below), you can see that the property is miles and miles away from any coastal areas, rivers or streams. More importantly, the home is elevated against its surroundings, so water flows away from the property, which is deemed low-risk.

- The area has no history of flooding, and this particular community has one of the most modern drainage systems in the state.

Screenshot of InsitePro, courtesy of Intermap Technologies. FEMA zones in red and orange

Screenshot of InsitePro, courtesy of Intermap Technologies. FEMA zones in red and orange

- Using Google Maps street view, we can estimate that the property is two to three feet above street level, which adds another layer of safety. Also, this view confirms that the area is essentially flat, so the property is not at the bottom of a bathtub.

- And, as with most homes in California, this property has no basement, so if water were to get into the house it would need to keep rising to cause further damage.

To an underwriter, it should be clear that this home has minimal risk from flooding. As a sanity check, she could compare losses from flood for this property (and properties like it in the community) to other hazards such as fire, earthquake, wind, lightning, theft, vandalism or internal water damage. How do they compare? What are the patterns?

For this specific home, the NFIP premium for flood coverage is $430, which provides $250,000 in building limit and $100,000 in contents protection. The price includes the $25 NFIP surcharge.

This is a mind-boggling amount of premium for the risk imposed. Consider that for roughly the same price you can get a full homeowners policy that covers all of these perils: fire, earthquake, wind, lightning, theft AND MORE! It is crazy to equate the risk of flood to the risk of all those standard homeowner perils,

combined! We provided this example to show that even without all the mapping and software tools available for pricing, what we can quickly conclude is that the NFIP pricing for these low-risk policies is absurdly high. Whatever the price “should” be for these types of risks, can you see that it MUST be a fraction of the price of a traditional homeowner’s policy? Don’t believe that either? Consider that the

Lloyd’s is marketing its low-risk flood policies as “inexpensive,” and brokers tell us privately that many base-level policies will be 50% to 75% less expensive than NFIP equivalents.

The news gets even better. There are tens of millions of houses like this case example, with technology now available to quickly find them. These risks aren’t the exception; these risks can be a market in their own right. Let the mental arithmetic commence!

Summary: Differentiate or Die!

The Unwanted Commodity

Most consumers of personal lines products don’t have the time or the ability to evaluate an insurance policy to determine whether it provides good value. Regrettably, most agents and brokers don’t have the time to help them either. So, when shopping for a product that they hope they will never use and that they are incapable of truly understanding, consumers will focus on the one thing they do understand: price.

Competing on price becomes a race to the bottom (yay! –

another soft market) and to death. But there is an opportunity here - carriers that compete on personal lines/homeowner insurance with benefits that are immediately apparent (like value, flexibility, service, conditions and, inevitably, price) have a rare chance to stake out significant new business, or to solidify their own share.

The flood insurance market is real, and it’s big enough for carriers to establish a healthy and competitive environment where service and quality will stand out, along with price. Carriers that would like to avoid dinosaur status can remain relevant and competitive, with no departure from insurance fundamentals – rate a risk, price it and sell it. It’s obvious, right?

Which carriers will be decisive and bold and begin to differentiate by offering flood capacity? Which carriers will evolve to keep pace or even lead the pack into the next generation of homeowner products? More importantly, which of you will lose market share and cease to exist in 10 years because you didn’t know what innovation looks like?

Screenshot of InsitePro, courtesy of Intermap Technologies. FEMA zones in red and orange

Screenshot of InsitePro, courtesy of Intermap Technologies. FEMA zones in red and orange