Heading into 2021, projections for U.S. inflation were mixed. At least two economists were on record saying “2021 will be a year plagued by numerous unwarranted inflation scares.” For the first three months of 2021, this outlook seemed reasonable, with consumer price index inflation averaging approximately 1.9%. Then, in April 2021, CPI inflation jumped to 4.2% and climbed steadily for the rest of the year. In December, inflation eventually reached a high for the year of 7%.

The last time CPI inflation exceeded 6% was back in the late 1970s/early 1980s. Inflation during that period was partly due to surges in the price of oil, while measures taken to curtail inflation included wage and price freezes, surcharges on imports and a break with the gold standard. At the time, the Federal Reserve implemented tight monetary policies that raised the federal funds rate from 10% to 20%. While these actions resulted in a recession, the policy proved effective, and in 1982 the trend of high inflation subsided.

Various reasons are given for the current spike in inflation, including supply bottlenecks, government policy, pent-up consumer demand for goods, imbalances in supply and demand and a lack of competition among corporations. Government stimulus spending since the pandemic has exceeded $5 trillion. Congress and the White House are still discussing additional stimulus spending. Continued availability of disposable income and hampered supply chains are expected to contribute to inflationary pressures well into 2022.

Not All Inflation Is Created Equal

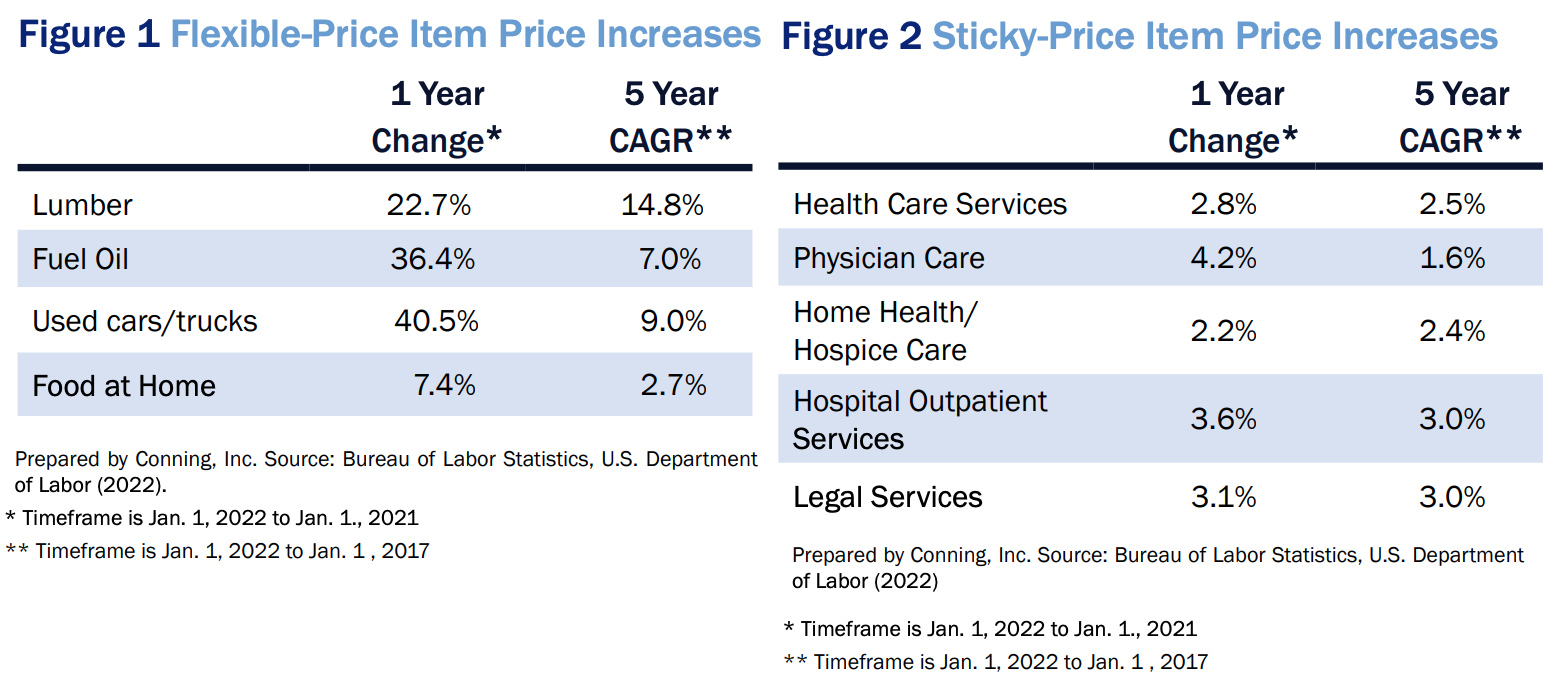

If the price changes for a particular CPI component occur less often, on average, than every 4.3 months, that component is called a “sticky-price” good. Goods that change prices more frequently are labeled “flexible-price” goods. Examples of sticky-price goods are medical care services, education, public transportation and motor vehicle maintenance. Examples of flexible-price goods are lumber, fuel oil, used cars/trucks and food at home.

As shown in Figures 1 and 2, most of the headline inflation during 2021 has come from price increases for flexible goods. Sticky-price goods—many of which underlie liability claim costs—have seen lower than headline inflation.

What Does This Mean for the MPL Industry?

As with most financial institutions, higher-than-expected inflation has adverse effects on the operations and results of property-casualty insurers.

Reserves — Insurers carry liabilities in the form of loss reserves that are intended to pay claims in the future. If inflation is higher than the rate built into the loss reserves, then future payments will be greater than expected. The impact of inflation varies by line of business, but an increase of one percentage point in inflation can raise the P/C industry combined ratio by two to three points. For personal lines of business, where liabilities are short in duration, a one-point increase in inflation may boost the combined ratio by less than one point. For a long-tailed line of business such as medical professional liability, the same one-point rise in inflation may increase the combined ratio by more than five points.

Rates — Insurers charge prices today that will pay for future claims. For some lines of business such as MPL, claims might not be paid for 10 years or more. If inflation proves to be greater than the inflation rate anticipated in the prices charged, then insurers may not have sufficient funds to pay claims. The dynamics of underestimating the inflation rate built into prices is like that of liabilities—i.e., a one-point increase in inflation will result in overall price inadequacies of 2% to 3%. These increases tend to vary by line of business.

Small differences between assumptions and actual inflation can have meaningful effects on the adequacy of prices. In a recent filing, a company assumed annual trend in pure premium--the combination of frequency and severity--of 0% and used a discount rate that assumed an annual return of 4% on its funds. If the assumptions were changed so the pure premium trend and the annual return on funds were both set at 2%, the company’s indicated rate change goes from an initial estimate of +34% to a revised +43%.

See also: https://www.insurancethoughtleadership.com/six-things-commentary/how-bad-will-inflation-get

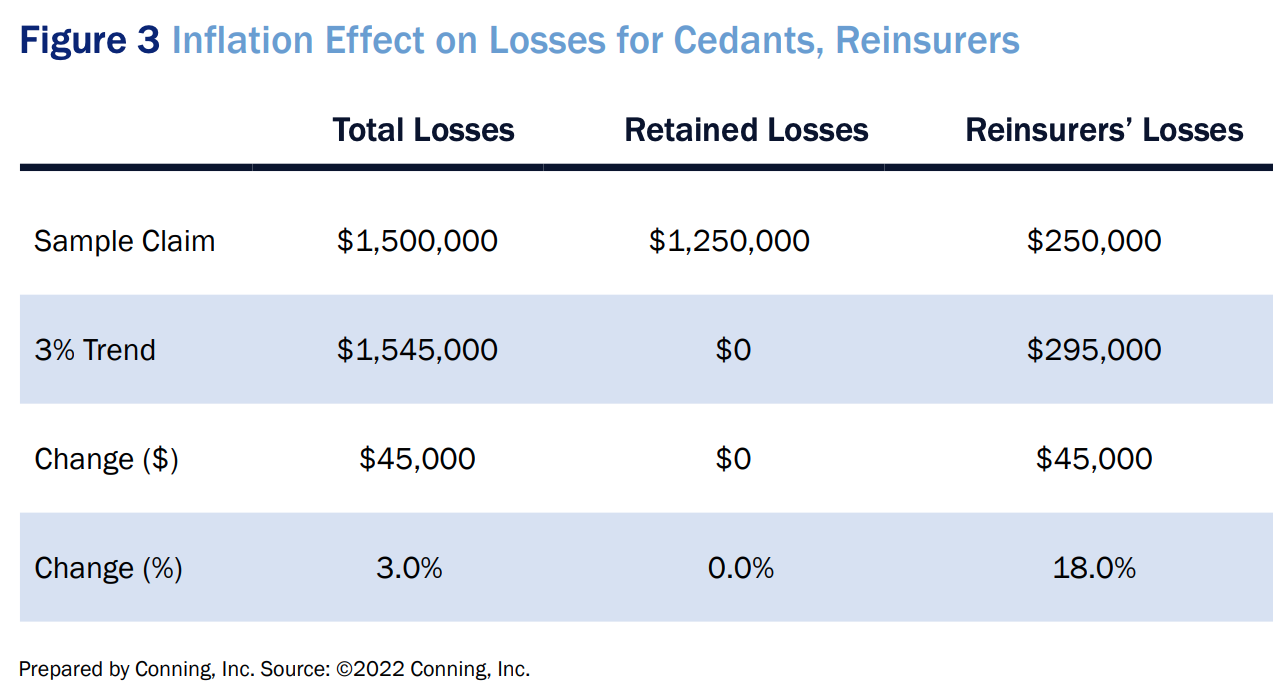

Reinsurance — Inflation affects losses in excess layers differently than losses in primary layers. Figure 3 shows a scenario where 3% inflation has 0% impact on a ceding company’s net losses but has an 18% impact on its reinsurer’s losses. Under the same conditions, an inflation rate of 5% would raise the reinsurer’s losses by 30%. The example helps demonstrate that, even in an environment where inflation is rising by low- to mid-single digits, the effect on losses ceded to reinsurers increases by multiples of the ground-up inflation rate.

Investments — Approximately 80% of the assets held by the P/C industry are in fixed income instruments such as Treasury, municipal and other bonds. These assets are structured to match the payments--cash flows--of the loss reserve liabilities they support. If companies sell current bonds so they can invest in newer, higher-yielding bonds, they will have to book losses upon the sale because higher interest rates drive down bond prices. However, if they hold onto current assets while the ultimate values of the underlying loss liabilities are increasing, there will be a mismatch between their assets and liabilities. This mismatch would have to be accounted for by a reduction in the company’s surplus. There is no efficient way for companies to hedge inflation risk, but they can try to dampen the risk through holding assets such as stocks and real estate, which bring their own inherent risks to a balance sheet.

And We Haven’t Even Mentioned Social Inflation

Another item affecting the insurance industry that is not included in any of the indices is potentially the largest inflation factor of all: social inflation. Broadly defined, social inflation refers to all ways in which insurers’ claims costs increase over and above economic inflation. While there is a clear trend in rising claim costs for liability lines of business, the overall increase in costs has been higher than the inflation in underlying costs such as medical care and wages.

Because the factors that drive social inflation are not quantitative, measurement of social inflation is difficult, if not impossible. These factors include anti-corporate sentiment, behaviors of the plaintiff bar, changing societal views and desensitization to large verdicts. However, to the extent social inflation is contributing to claim costs, insurers and reinsurers must attempt to quantify its impact so liabilities and prices are adequate. In an attempt to quantify the impact of social inflation on commercial auto losses, the Insurance Information Institute recently performed a joint study with the Casualty Actuarial Society. The study concluded that, from 2010 to 2019, approximately $21 billion, or 14%, of commercial auto losses could not be explained by regular increases in the CPI. The authors of the study stated that they found evidence of social inflation in other liability (occurrence) and medical professional liability (claims-made), but they did not provide measurements for these lines of business.

See also: Insurers' Social Inflation Problem

Inflation’s Bottom Line

The CPI and other economic indices such as the Producer Price Index are valuable resources, but arguments have been made that these indices have inherent flaws that can distort their measures of inflation. For example, the CPI is heavily weighted toward urban consumption and may not be an accurate measure of the price of goods for suburban and rural areas, where prices may be higher due to distance from production centers. The CPI is also criticized for not representing the innovation of products that could be years away from inclusion in the calculation of the CPI.

The 7% increase in inflation in 2021 has captured many headlines, and market expectations suggest inflation rates are likely to remain higher over the near term. January 2022 CPI increase was 7.5% and February 2022 increase was 7.9%. According to the February edition of the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia Survey of Professional Forecasters, headline CPI in 2022 and 2023 will be 3.8% and 2.4%, respectively. While insurers have been raising prices in response to rising costs, it remains to be seen if increases in loss reserves will follow. For the past 15 years, the industry’s carried liabilities for MPL have been above average in terms of redundancies. However, if inflation is greater than anticipated in the reserves, these redundancies can turn into deficiencies. As such, property-casualty insurers should be stress testing their operations and considering strategies to counter concern about inflation and potential impacts on both sides of their balance sheets.

This article previously appeared in Inside Medical Liability magazine.