Although organizations are exempt from the California law when “assembling or collecting information about natural persons for the primary purpose of providing the information to an insurance institution or agent for insurance transactions”—thanks to Assembly Bill 981, which was passed in May—organizations are still subject to its requirements when the scope and use of personal data exceeds those specific operations. In many cases, the compliance concerns of insurance companies will be solely with that of their policyholders, so it is in the best interest of both parties to ensure steadfast organizational compliance with an emphasis on reducing risk and anticipating future regulations.

See also: Blockchain, Privacy and Regulation

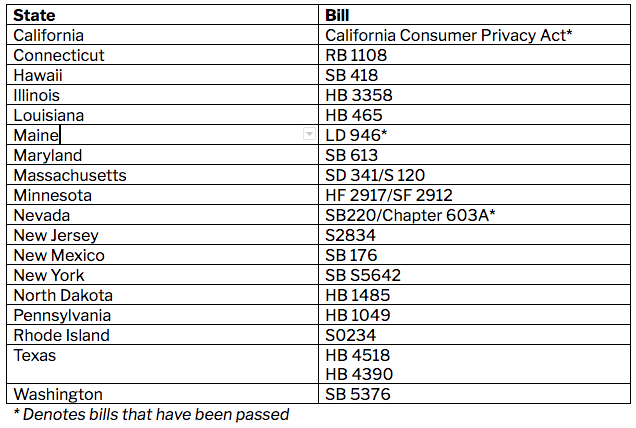

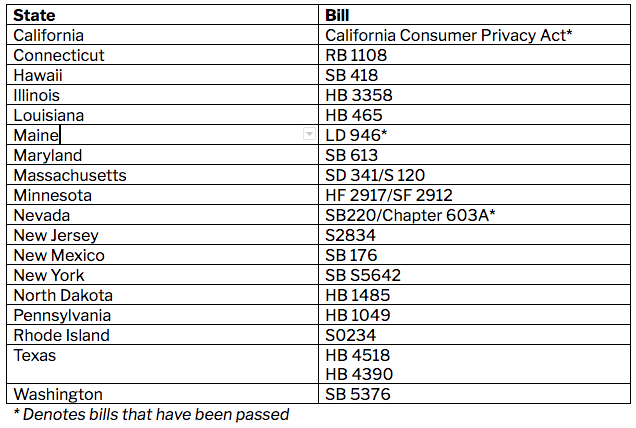

Of particular importance to these insurers and their insureds is the controversial concept of private right of action, which allows individuals whose privacy has been violated to bring civil suits against noncompliant parties. Originally, this portion of the California law could have exponentially increased the financial consequences of a breach by subjecting violators to class-action claims of damages from victims, on top of the compliance-related fines levied by the state. It has since been limited to injunctive or declaratory relief, but other developing statutes include language similar to the original bill’s treatment of private right of action. Louisiana, Massachusetts, New York, North Dakota and Rhode Island all are working on bills that include a private right of action, with New York’s being especially expansive and potentially heavy-handed toward violators. In addition to including a private right of action, New York’s proposal has no minimum gross revenue requirement, meaning all companies—regardless of size—will be subject to the law’s rules and penalties. This has led critics to question the feasibility of fairly enforcing what they deem to be overly broad regulations aimed at punishing well-meaning organizations that cannot keep up with the evolving privacy space.

In terms of its impact on the insurance industry, the resulting legislative inconsistency will hit the big names the hardest, but it still does no favors for mid-size carriers struggling to keep up with their state or regional laws. In addition to meeting their own compliance obligations, they will have to accurately gauge the risk and potential penalties presented by the difficulty policyholders will have satisfying theirs. Insurers might not have to walk through the minefield, but they will have to clean up the mess inside it once something goes wrong.

As we discussed in a previous post, the difficulty insurance companies already experience when attempting to create reliable cyberinsurance policies is inhibiting the industry’s ability to provide much-needed coverage. The private right of action and other uncertain aspects of these laws further complicate the task of accurately estimating and pricing the cost of cyberinsurance coverage by expanding the potential recompense for breach victims. When coupled with the fact that no federal privacy law exists—allowing each state to establish its own set of rules for what constitutes personal data and how it should be protected—offering cyberinsurance can seem like an almost untenable prospect. However, a risk-reducing, compliance-enabling solution exists in the marketplace: tokenization.

See also: Mobile Apps and the State of Privacy

Tokenization, such as that offered by the TokenEx Cloud Security Platform, especially excels at reducing risk through its use of pseudonymization and secure data vaults. Pseudonymization, also known as deidentification, is the process of desensitizing data to render it untraceable to its original data subject. It does so by replacing identifying elements of the data with a nonsensitive equivalent, or token, and storing the original data in a cloud-based data vault. This virtually eliminates the risk of theft in the event of a data breach, and, as a result, tokenization is recognized as an appropriate technical mechanism for protecting sensitive data in compliance with the CCPA and other regulatory compliance obligations. Because tokenization satisfies controls concerning the processing of sensitive data, it can prevent losses stemming from fines and other penalties as a result of noncompliance.

As new laws emerge and the privacy landscape in the U.S. continues to shift, it is crucial for both insurance companies and their policyholders to prioritize risk minimization. And tokenization is an essential tool for significantly reducing the likelihood of a cyber event, and as a result, a claim.

Although organizations are exempt from the California law when “assembling or collecting information about natural persons for the primary purpose of providing the information to an insurance institution or agent for insurance transactions”—thanks to Assembly Bill 981, which was passed in May—organizations are still subject to its requirements when the scope and use of personal data exceeds those specific operations. In many cases, the compliance concerns of insurance companies will be solely with that of their policyholders, so it is in the best interest of both parties to ensure steadfast organizational compliance with an emphasis on reducing risk and anticipating future regulations.

See also: Blockchain, Privacy and Regulation

Of particular importance to these insurers and their insureds is the controversial concept of private right of action, which allows individuals whose privacy has been violated to bring civil suits against noncompliant parties. Originally, this portion of the California law could have exponentially increased the financial consequences of a breach by subjecting violators to class-action claims of damages from victims, on top of the compliance-related fines levied by the state. It has since been limited to injunctive or declaratory relief, but other developing statutes include language similar to the original bill’s treatment of private right of action. Louisiana, Massachusetts, New York, North Dakota and Rhode Island all are working on bills that include a private right of action, with New York’s being especially expansive and potentially heavy-handed toward violators. In addition to including a private right of action, New York’s proposal has no minimum gross revenue requirement, meaning all companies—regardless of size—will be subject to the law’s rules and penalties. This has led critics to question the feasibility of fairly enforcing what they deem to be overly broad regulations aimed at punishing well-meaning organizations that cannot keep up with the evolving privacy space.

In terms of its impact on the insurance industry, the resulting legislative inconsistency will hit the big names the hardest, but it still does no favors for mid-size carriers struggling to keep up with their state or regional laws. In addition to meeting their own compliance obligations, they will have to accurately gauge the risk and potential penalties presented by the difficulty policyholders will have satisfying theirs. Insurers might not have to walk through the minefield, but they will have to clean up the mess inside it once something goes wrong.

As we discussed in a previous post, the difficulty insurance companies already experience when attempting to create reliable cyberinsurance policies is inhibiting the industry’s ability to provide much-needed coverage. The private right of action and other uncertain aspects of these laws further complicate the task of accurately estimating and pricing the cost of cyberinsurance coverage by expanding the potential recompense for breach victims. When coupled with the fact that no federal privacy law exists—allowing each state to establish its own set of rules for what constitutes personal data and how it should be protected—offering cyberinsurance can seem like an almost untenable prospect. However, a risk-reducing, compliance-enabling solution exists in the marketplace: tokenization.

See also: Mobile Apps and the State of Privacy

Tokenization, such as that offered by the TokenEx Cloud Security Platform, especially excels at reducing risk through its use of pseudonymization and secure data vaults. Pseudonymization, also known as deidentification, is the process of desensitizing data to render it untraceable to its original data subject. It does so by replacing identifying elements of the data with a nonsensitive equivalent, or token, and storing the original data in a cloud-based data vault. This virtually eliminates the risk of theft in the event of a data breach, and, as a result, tokenization is recognized as an appropriate technical mechanism for protecting sensitive data in compliance with the CCPA and other regulatory compliance obligations. Because tokenization satisfies controls concerning the processing of sensitive data, it can prevent losses stemming from fines and other penalties as a result of noncompliance.

As new laws emerge and the privacy landscape in the U.S. continues to shift, it is crucial for both insurance companies and their policyholders to prioritize risk minimization. And tokenization is an essential tool for significantly reducing the likelihood of a cyber event, and as a result, a claim.CCPA: First of Many Painful Privacy Laws

The California Consumer Privacy Act amps up the need for cyberinsurance -- and for "tokenization."

Although organizations are exempt from the California law when “assembling or collecting information about natural persons for the primary purpose of providing the information to an insurance institution or agent for insurance transactions”—thanks to Assembly Bill 981, which was passed in May—organizations are still subject to its requirements when the scope and use of personal data exceeds those specific operations. In many cases, the compliance concerns of insurance companies will be solely with that of their policyholders, so it is in the best interest of both parties to ensure steadfast organizational compliance with an emphasis on reducing risk and anticipating future regulations.

See also: Blockchain, Privacy and Regulation

Of particular importance to these insurers and their insureds is the controversial concept of private right of action, which allows individuals whose privacy has been violated to bring civil suits against noncompliant parties. Originally, this portion of the California law could have exponentially increased the financial consequences of a breach by subjecting violators to class-action claims of damages from victims, on top of the compliance-related fines levied by the state. It has since been limited to injunctive or declaratory relief, but other developing statutes include language similar to the original bill’s treatment of private right of action. Louisiana, Massachusetts, New York, North Dakota and Rhode Island all are working on bills that include a private right of action, with New York’s being especially expansive and potentially heavy-handed toward violators. In addition to including a private right of action, New York’s proposal has no minimum gross revenue requirement, meaning all companies—regardless of size—will be subject to the law’s rules and penalties. This has led critics to question the feasibility of fairly enforcing what they deem to be overly broad regulations aimed at punishing well-meaning organizations that cannot keep up with the evolving privacy space.

In terms of its impact on the insurance industry, the resulting legislative inconsistency will hit the big names the hardest, but it still does no favors for mid-size carriers struggling to keep up with their state or regional laws. In addition to meeting their own compliance obligations, they will have to accurately gauge the risk and potential penalties presented by the difficulty policyholders will have satisfying theirs. Insurers might not have to walk through the minefield, but they will have to clean up the mess inside it once something goes wrong.

As we discussed in a previous post, the difficulty insurance companies already experience when attempting to create reliable cyberinsurance policies is inhibiting the industry’s ability to provide much-needed coverage. The private right of action and other uncertain aspects of these laws further complicate the task of accurately estimating and pricing the cost of cyberinsurance coverage by expanding the potential recompense for breach victims. When coupled with the fact that no federal privacy law exists—allowing each state to establish its own set of rules for what constitutes personal data and how it should be protected—offering cyberinsurance can seem like an almost untenable prospect. However, a risk-reducing, compliance-enabling solution exists in the marketplace: tokenization.

See also: Mobile Apps and the State of Privacy

Tokenization, such as that offered by the TokenEx Cloud Security Platform, especially excels at reducing risk through its use of pseudonymization and secure data vaults. Pseudonymization, also known as deidentification, is the process of desensitizing data to render it untraceable to its original data subject. It does so by replacing identifying elements of the data with a nonsensitive equivalent, or token, and storing the original data in a cloud-based data vault. This virtually eliminates the risk of theft in the event of a data breach, and, as a result, tokenization is recognized as an appropriate technical mechanism for protecting sensitive data in compliance with the CCPA and other regulatory compliance obligations. Because tokenization satisfies controls concerning the processing of sensitive data, it can prevent losses stemming from fines and other penalties as a result of noncompliance.

As new laws emerge and the privacy landscape in the U.S. continues to shift, it is crucial for both insurance companies and their policyholders to prioritize risk minimization. And tokenization is an essential tool for significantly reducing the likelihood of a cyber event, and as a result, a claim.

Although organizations are exempt from the California law when “assembling or collecting information about natural persons for the primary purpose of providing the information to an insurance institution or agent for insurance transactions”—thanks to Assembly Bill 981, which was passed in May—organizations are still subject to its requirements when the scope and use of personal data exceeds those specific operations. In many cases, the compliance concerns of insurance companies will be solely with that of their policyholders, so it is in the best interest of both parties to ensure steadfast organizational compliance with an emphasis on reducing risk and anticipating future regulations.

See also: Blockchain, Privacy and Regulation

Of particular importance to these insurers and their insureds is the controversial concept of private right of action, which allows individuals whose privacy has been violated to bring civil suits against noncompliant parties. Originally, this portion of the California law could have exponentially increased the financial consequences of a breach by subjecting violators to class-action claims of damages from victims, on top of the compliance-related fines levied by the state. It has since been limited to injunctive or declaratory relief, but other developing statutes include language similar to the original bill’s treatment of private right of action. Louisiana, Massachusetts, New York, North Dakota and Rhode Island all are working on bills that include a private right of action, with New York’s being especially expansive and potentially heavy-handed toward violators. In addition to including a private right of action, New York’s proposal has no minimum gross revenue requirement, meaning all companies—regardless of size—will be subject to the law’s rules and penalties. This has led critics to question the feasibility of fairly enforcing what they deem to be overly broad regulations aimed at punishing well-meaning organizations that cannot keep up with the evolving privacy space.

In terms of its impact on the insurance industry, the resulting legislative inconsistency will hit the big names the hardest, but it still does no favors for mid-size carriers struggling to keep up with their state or regional laws. In addition to meeting their own compliance obligations, they will have to accurately gauge the risk and potential penalties presented by the difficulty policyholders will have satisfying theirs. Insurers might not have to walk through the minefield, but they will have to clean up the mess inside it once something goes wrong.

As we discussed in a previous post, the difficulty insurance companies already experience when attempting to create reliable cyberinsurance policies is inhibiting the industry’s ability to provide much-needed coverage. The private right of action and other uncertain aspects of these laws further complicate the task of accurately estimating and pricing the cost of cyberinsurance coverage by expanding the potential recompense for breach victims. When coupled with the fact that no federal privacy law exists—allowing each state to establish its own set of rules for what constitutes personal data and how it should be protected—offering cyberinsurance can seem like an almost untenable prospect. However, a risk-reducing, compliance-enabling solution exists in the marketplace: tokenization.

See also: Mobile Apps and the State of Privacy

Tokenization, such as that offered by the TokenEx Cloud Security Platform, especially excels at reducing risk through its use of pseudonymization and secure data vaults. Pseudonymization, also known as deidentification, is the process of desensitizing data to render it untraceable to its original data subject. It does so by replacing identifying elements of the data with a nonsensitive equivalent, or token, and storing the original data in a cloud-based data vault. This virtually eliminates the risk of theft in the event of a data breach, and, as a result, tokenization is recognized as an appropriate technical mechanism for protecting sensitive data in compliance with the CCPA and other regulatory compliance obligations. Because tokenization satisfies controls concerning the processing of sensitive data, it can prevent losses stemming from fines and other penalties as a result of noncompliance.

As new laws emerge and the privacy landscape in the U.S. continues to shift, it is crucial for both insurance companies and their policyholders to prioritize risk minimization. And tokenization is an essential tool for significantly reducing the likelihood of a cyber event, and as a result, a claim.