With their variety of business strategies and product innovations, financial services organizations often have very complex corporate structures. The mix of regulated operating, distribution, investment, holding and dormant companies - together with various special-purpose vehicles - means that few employees fully know the complexity of an enterprise's legal entity structure.

Generally, management prefers simplicity and accountability. Accordingly, it typically organizes enterprises into distinct, separately managed, strategic business units (SBUs), which are overlaid on top of the existing legal entity structure, with the SBUs sharing various legal entities. This management approach creates a simplified internal view of financial performance relative to the legal entity structure; however, it often masks the considerable extra work (and therefore potentially avoidable cost) associated with the corporate structure within an organization's corporate accounting, tax and other back-office functions.

Few organizations start off with a complex corporate structure or seek to achieve one, but a combination of factors can lead to complexity:

- Growth by acquisition - Entities inherited as part of an acquisition and entities (such as holding companies) formed to make acquisitions;

- Tax strategies - Entities formed to minimize multi-jurisdictional taxation, preserve the utility of tax attributes (such as basis, losses and credits) or effectively manage product state taxes;

- Historical regulatory requirements - Companies formed to facilitate various regulated pricing tiers (particularly in property and casualty (P&C) insurance); and,

- Business line expansion and reorganization - Organic growth into new product areas, alignment within different market segments (sometimes under reinsurance pooling arrangements), discontinued business, etc.

Complexity adds to administrative costs and can slow production of management information. In the capital structure work that PwC performs, we frequently find that a company's structure is out of date; for example, the original rationale for a tax planning structure is no longer applicable because of a change in law, or a legal entity structure established to facilitate a line of business has survived even though the line of business has not. As another example, an entity that was established before the advent of the entity classification election regime (i.e. "check the box" rule) now may be unnecessary to achieve the intended tax benefits. Accordingly, organizations should examine the costs and benefits of maintaining current structures.

The complexity of corporate structures in financial services is evident in the insurance industry's use of legal entities. As the table below shows, among P&C and life and health (L&H) insurers, the top 25 insurance groups hold a majority of industry capital (69% in P&C, 58% in L&H). Despite this concentration, there is evidence that inefficiencies exist: There is a high number of dormant entities relative to total legal entities and the number of domiciles some groups are managing. The number of domiciles tends to be five or fewer for most insurers, but in some extreme cases there are as many as 12 domiciles for P&C companies and 31 for L&H companies (primarily because of health maintenance organization (HMO) entities). When factoring in the potential costs (real and opportunity costs) of maintaining unused or underutilized legal entities, the impact on the industry as a whole is very real.

| Insurance industry capital is relatively concentrated | ||

| P&C | L&H | |

| Groups | ~330 | ~250 |

| Legal entities | ~2,700 | ~1,800 |

| Capital in top 25 groups | 69% | 58% |

But there are indications of inefficiency

| Dormant entities | 150+ | 300+ |

| Fronting entities | 500+ | 100+ |

| Range of domiciles/groups | 1-12 | 1-31 |

Source: SNL, PwC Analysis

Legal entity cost

Organizations rightly consider the costs of administering legal entities a normal part of doing business. Such frictional costs vary by organization and entity usage and typically include:

- Financial reporting costs - Licensed insurance companies require separate annual and quarterly financial statement preparation in their state of domicile. The time spent on statement preparation correlates to complexity. The greater the number of legal entities, the greater the complexity and the higher the risk of misstatement.

- Auditing costs - These costs will vary with the size and complexity of the balance sheet. Again, costs tend to be correlated with complexity (e.g., degree of intercompany transactions, complex reinsurance structures, investments/financial products, etc.).

- State assessments - Premium or loss-based assessments for a variety of state programs will vary in size relative to the business written in the legal entity. It is important to recognize that minimum assessments also can apply even when business is no longer written on a direct or net basis.

- Regulatory exams - State regulators conduct both market conduct exams and financial exams of insurance companies domiciled in their respective jurisdictions. Market conduct exams occur on an as-needed basis and relate to examination of operational (sales, underwriting, claims) business practices. Certain domiciles are more challenging than others. Financial exams occur every three to five years, at the insurance company's expense.

- Tax - Each legal entity in the structure adds to the company's overall compliance burden, as insurance companies are required to prepare and file forms with state and federal tax authorities on a periodic basis even when dormant. A company also may be required to respond to periodic inquiries about its activities, or lack thereof, and may be subject to minimum taxes and filing fees. Active operating companies must monitor and manage the interplay of premium tax rates and retaliatory taxes, which arise when states in lower tax jurisdictions increase state taxes to match the level of the domicile state, if it is higher.

- Management time - Spans all of the above areas. The more complex a legal entity structure, the more time middle management and, in some cases, senior management have to spend on issues related to excess legal entities.

In light of these frictional costs, the expense of administering an overly complex legal entity structure can be considerable. Eliminating redundant or unused entities through merging companies, outright sale of the insurance company (or companies) or clearing out the liabilities and selling a "shell" company can result in significant savings.

Improving access to capital

Moving capital through legal entities can be complicated by regulatory constraints and often involves frictional costs such as sub-optimal tax consequences (e.g., withholding taxes on dividends from a foreign subsidiary and excise taxes on premiums paid to a foreign affiliate). Capital trapped in dormant or underutilized entities will provide sub-optimal returns and therefore serve as a drag on the overall group return on equity. For example, an organization with a 15% corporate required rate of return and a 5% average investment portfolio rate of return has a 10% opportunity cost of maintaining the capital in a redundant legal entity. Accordingly, one of the few positive outcomes of the financial crisis has been insurers' streamlining their corporate structures to simplify internal access to capital and gain capital efficiency.

One method of improving capital deployment in a dormant or underutilized entity is through merger with a continuing entity. However, before merging a licensed company out of existence, insurers need to consider the marketability of the unwanted entity in terms of the number and location of state licenses, the degree to which the company has gross liabilities, the type of liabilities (e.g., excluding asbestos and environmental), the domicile state, the credit quality of the counterparty backing the reinsurance contract or contracts used to create the shell, etc. In light of the regulatory hurdles and time delays that accompany the obtainment of state licenses, there is a market for selling licensed companies as "shell" companies. The process typically requires transferring insurance liabilities out of the legal entity through indemnity - or preferably assumption - reinsurance. This market has yielded significant value to its customers. That said, it is critical to gain proper restructuring advice before entering into these transactions because undesirable accounting and risk-based capital outcomes can result from poorly structured reinsurance transactions.

Simplifying corporate structure: Opportunities & challenges

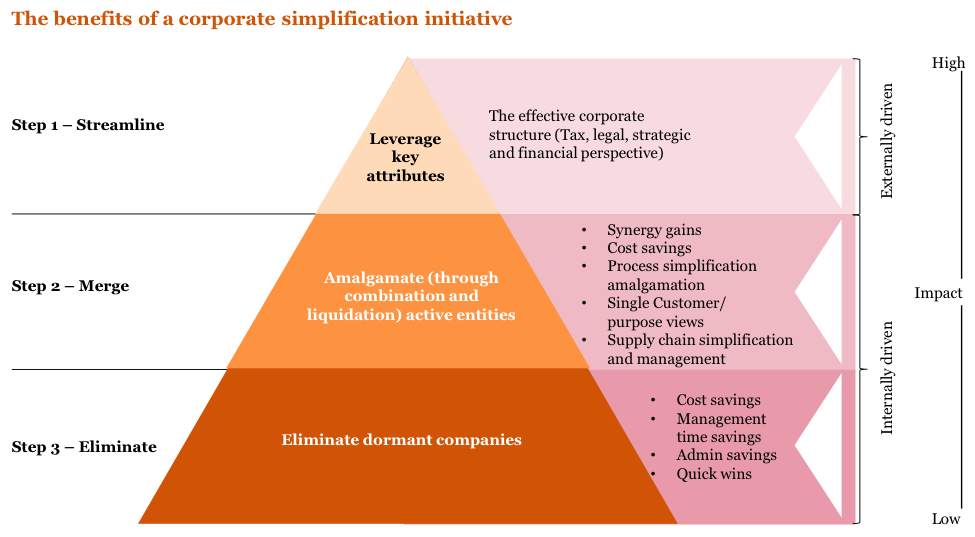

Eliminating unnecessary organizational complexity and reducing associated frictional expenses are the main reasons to undertake a corporate simplification program. The benefits of corporate simplification are:

- Streamlined financial management across a manageable number of entities;

- Removal of unnecessary frictional costs;

- Reduced overall state tax burden, leading to competitive advantages in market pricing;

- Consolidation of entities within favorable state regulatory environments;

- Identification of alternative capital structures or mechanisms to free trapped capital for the top-tier company to use for other purposes;

- Generation of capital through the sale of unnecessary licensed companies as "shell" companies.

However, the simplification program does present some challenges:

- Internal resource constraints may limit design and implementation of the simplification;

- Regulatory approvals for material changes may prolong implementation;

- Product filings may need to be updated;

- Re-domestication of entities may present political or regulatory issues (including perceived or real job losses or transfers, closed block regulatory requirements, etc.) that can delay the process;

- Changes in legal entity structure can affect near-term business operations and supporting technology platforms. For example, changes in legal entities used by the insurance underwriting organization may require process changes in the distribution channel as new and renewal business is mapped to different entities;

- Selling or merging active operating companies can also present challenges for management, including: identifying intercompany accounts between merged entities; updating intercompany agreements, such as intercompany reinsurance pooling agreements, to reflect the changes; cleaning up outstanding legal entity accounting reconciliations, if any; re-mapping ledgers for historical data; re-mapping upstream company eliminations; creating and maintaining merged company historical financials for statutory and GAAP/IFRS financial statements; locating and analyzing details of historic tax attributes (such as basis and earnings and profits) and studying qualification for tax-free reorganization; potential reversal of subsidiary surplus impacts from asset purchase/sale transactions within the holding company structure; and potential scrutiny over differing methodologies, if any, used for accounting (e.g., deferred acquisition cost) or actuarial reserve methodologies used by the entities to be merged.

The corporate simplification process

Many large insurance organizations have some level of corporate simplification on their annual to-do list, but the initiative often gets pushed aside because of gaps between corporate and business priorities and available resources. The corporate simplification process requires a champion who can take into account and balance varying points of view, call upon required resources, facilitate project management and authorize access to subject-matter expertise. Moreover, a corporate simplification program must balance corporate (tax, regulatory, governance and financial reporting costs) and business (customer, distribution, products, process and technology) needs and considerations. Depending on the complexity of the organization and underlying challenges, a simplification initiative can take several months to well over a year.

The three stages of such an initiative include:

- Assess - The ultimate goal of a corporate simplification process is a streamlined corporate structure that corresponds to business core competencies and strategy. This structure will have an efficient balance of cost, risk, regulatory, tax, capital, governance and operational parameters that aligns business operations with the legal entity structure. In the initial phase of the initiative, representatives from corporate and business areas must come together to review the current use of legal entities and create the desired future organizational structure, as well as take into account the existing corporate environment (rather than what existed in the past). If the simplification effort is part of a broader business unit re-alignment, the assessment and design phase will require a significant commitment of time and effort to redefine the desired business strategy. If the simplification is taking place within a well-defined business unit structure, then the focus can be limited to streamlining and reducing overall cost within the existing business unit strategies.

A complete inventory of legal entities should be created outlining information such as the business use, applicable business unit, domicile, direct and net business written (for insurance companies only), required/minimum capital, actual capital, potential for elimination, and other information as defined by the group. Furthermore, to complete the assessment of the simplification effort, a business impact analysis that includes a premium tax analysis by state domicile and a regulatory domicile analysis should occur at this stage. Companies also need to carefully look at their portfolio of companies to ensure they have the entities they need today and for the near future.

- Design - As the plan starts to take shape, the project team must conduct a deeper analysis of accounting, business and technology transition issues. The deliverable will be a proposed road map that:

- Outlines a streamlined legal entity organization structure with greater capital efficiency and alignment with business strategy;

- Identifies the proposed combinations/eliminations of insurance and non-insurance entities;

- Describes the proposed movement of capital (including extraordinary dividends required) and reinsurance transactions to effectuate the change (if applicable); and

- Establishes a communication plan within a high-level timeline.

This outline of proposed changes must be well vetted internally before the organization approaches regulators, rating agencies and other constituents.

- Implement - Once the design is ready, project management and subject-matter expert resource requirements must be confirmed. Program and change management and associated governance structures are critical throughout the planning and implementation phases as the number of work streams, constituents, interdependencies and issues can be substantial for larger-scale simplification programs. Once the team is in place, it must create detailed implementation project plans, identify quick wins, establish an effective communication plan and establish an issue/dependency management process. Communication to all constituents - employees, sales force/agents, regulators, rating agencies and policyholders - is vital in any simplification initiative.

Following the design phase, those entities that have common activities, objectives, operational process or customer segmentation can be merged, which should effectively align business and legal entity structure. The remaining, redundant legal entities should be eliminated, sold as-is or sold as a shell. This final step will result in cost savings and the raising of new capital through the sale of licensed shell companies.

Conclusion: Corporate simplification is a priority

In light of the need to be nimble while reducing costs, corporate simplification should be at the top of the corporate to-do list. A well-managed corporate simplification program provides strategic alignment of entities, reduces costs and facilitates more efficient use of capital. The companies that execute an effective corporate simplification process and maintain a commitment to simplification over time will succeed in reducing costs and be able to devote their time and attention to valuable activities.