Wearables and self-reported data can provide Personalized Activity Intelligence (PAI), which measures cardiorespiratory fitness.

I bought a new mountain bike this summer. I already had two perfectly good bicycles in the garage, but there’s nothing like a new toy to get you motivated. Hitting the trails these days involves monitoring my data. I’m interested to test myself using Personalized Activity Intelligence (PAI), a health score that measures cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF).

PAI draws heart rate activity from wearables, such as Fitbit and Apple Watch. It uses that information, along with self-reported data, to guide me toward the most beneficial amount of exercise for my body. Using all that data, the weekly effort I put into physical activity is translated into a single PAI score. Maintaining 100 PAI reduces my risk of cardiovascular disease and early death. I might like to live longer now that I’ve spent EUR2,500 on this new bike….

PAI takes account of my resting and maximum heart rate over a seven-day rolling period, adjusted for exercise intensity to reflect my VO2 max, a measure of CRF. Cycling should increase my heart rate above a threshold, and into the CRF training zone, generating PAI points. Consistently maintaining 100 PAI will derive the health benefits.

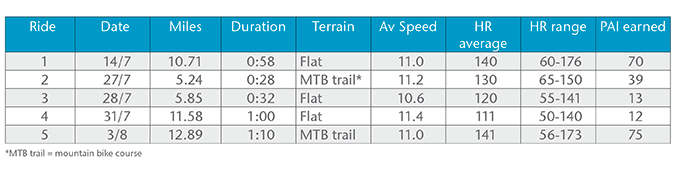

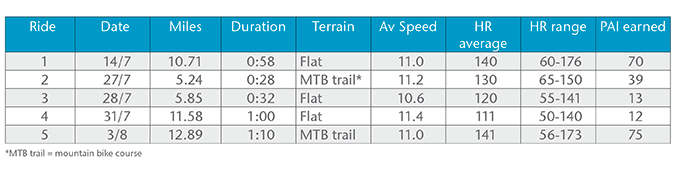

PAI requires several weeks of activity data to properly attune to my VO2 max, but my first five rides provide an indication of what’s to come (see Figure below). PAI uses the first ride data to begin calibrating the algorithm to me -- the score is irrelevant. My second ride ends abruptly with a puncture and a fall, but by ride four I’m back in the zone, and by ride five back in the woods.

My average heart rate dropped over the first four rides, which suggests that my fitness reserve was decent and that I’ve quickly added some heart health to the equation. Although my average speed was consistent, the effort involved measured by heart rate and, ultimately, the points earned, trend downward.

See also: How to Link Heart Health to Insurance

It’s clear that longer duration coupled with higher attained heart rate scores more points. I must up my game because the algorithm calibrates to my personal heart effort. With PAI, very low-intensity exercise doesn’t contribute to increased levels of CRF, while fitter people with higher heart rate reserve face a tougher threshold to accumulate PAI points.

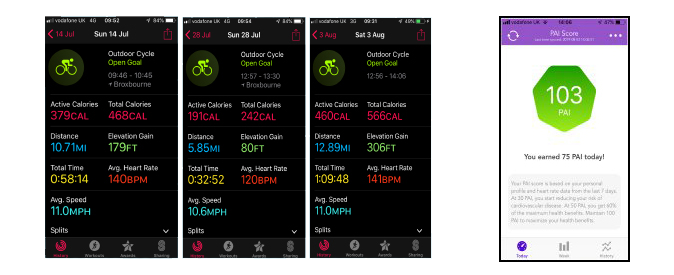

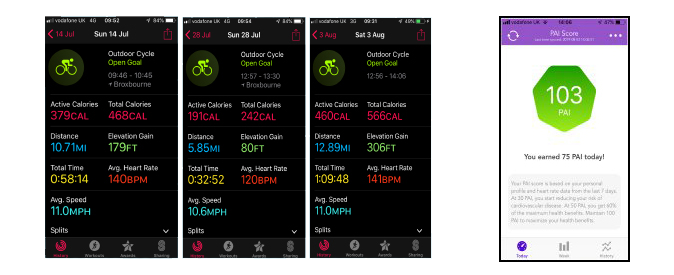

Now the PAI algorithm is adjusting to my profile, and I’m discovering the effort required to earn a protective score. I go back out on the bike for ride five and earn 75 points; the maximum possible in one day. This isn’t a surprise. The route is longer and more challenging, and I ride harder because I’m already feeling fitter (see Figure below).

The algorithm will continue to adjust to my exercise behavior over the next few months. As my CRF increases, I will discover that running on a treadmill for 30 minutes is less fun and nets me fewer points. I will find that my daily brisk walking and average of 6,000 steps contribute but do not raise my heart effort enough to strongly influence my CRF. Running and walking will supplement my PAI score, but to score 100 -- enough to affect my long-term health and get good value out of this bike -- well, that simply requires greater effort.

For further background. read my blog Heart Health - Why Linking It to Insurance Is a Winning Formula.

My average heart rate dropped over the first four rides, which suggests that my fitness reserve was decent and that I’ve quickly added some heart health to the equation. Although my average speed was consistent, the effort involved measured by heart rate and, ultimately, the points earned, trend downward.

See also: How to Link Heart Health to Insurance

It’s clear that longer duration coupled with higher attained heart rate scores more points. I must up my game because the algorithm calibrates to my personal heart effort. With PAI, very low-intensity exercise doesn’t contribute to increased levels of CRF, while fitter people with higher heart rate reserve face a tougher threshold to accumulate PAI points.

Now the PAI algorithm is adjusting to my profile, and I’m discovering the effort required to earn a protective score. I go back out on the bike for ride five and earn 75 points; the maximum possible in one day. This isn’t a surprise. The route is longer and more challenging, and I ride harder because I’m already feeling fitter (see Figure below).

My average heart rate dropped over the first four rides, which suggests that my fitness reserve was decent and that I’ve quickly added some heart health to the equation. Although my average speed was consistent, the effort involved measured by heart rate and, ultimately, the points earned, trend downward.

See also: How to Link Heart Health to Insurance

It’s clear that longer duration coupled with higher attained heart rate scores more points. I must up my game because the algorithm calibrates to my personal heart effort. With PAI, very low-intensity exercise doesn’t contribute to increased levels of CRF, while fitter people with higher heart rate reserve face a tougher threshold to accumulate PAI points.

Now the PAI algorithm is adjusting to my profile, and I’m discovering the effort required to earn a protective score. I go back out on the bike for ride five and earn 75 points; the maximum possible in one day. This isn’t a surprise. The route is longer and more challenging, and I ride harder because I’m already feeling fitter (see Figure below).

The algorithm will continue to adjust to my exercise behavior over the next few months. As my CRF increases, I will discover that running on a treadmill for 30 minutes is less fun and nets me fewer points. I will find that my daily brisk walking and average of 6,000 steps contribute but do not raise my heart effort enough to strongly influence my CRF. Running and walking will supplement my PAI score, but to score 100 -- enough to affect my long-term health and get good value out of this bike -- well, that simply requires greater effort.

For further background. read my blog Heart Health - Why Linking It to Insurance Is a Winning Formula.

The algorithm will continue to adjust to my exercise behavior over the next few months. As my CRF increases, I will discover that running on a treadmill for 30 minutes is less fun and nets me fewer points. I will find that my daily brisk walking and average of 6,000 steps contribute but do not raise my heart effort enough to strongly influence my CRF. Running and walking will supplement my PAI score, but to score 100 -- enough to affect my long-term health and get good value out of this bike -- well, that simply requires greater effort.

For further background. read my blog Heart Health - Why Linking It to Insurance Is a Winning Formula.