The property/casualty insurance litigation industry maintains the largest negotiation network in the world. Tens of thousands of insurance claim professionals partner with more than 30,000 defense attorneys to reach the most appropriate resolutions on more than 750,000 litigated claims annually.

Because our company’s mission is to help insurance litigation defense teams be more successful, we are obsessed with data that paints a clear picture of the litigation environment in which a litigated file is being defended.

Why? Because the litigation environment defines the true BATNA, or Best Alternative to a Negotiated Agreement. And in our world of litigation, the only BATNA available to us is taking a case to trial.

The litigation environment is composed of many factors. The venue, the plaintiff attorney, the judge – all these entities have track records, and that information is critical to quantifying the BATNA, establishing settlement values, deciding which cases to try, and not overpaying on files.

Doing this well yields significant short- and long-term benefit. The amounts paid on litigated files drive the case values on pre-litigated files. Given this broad impact on all negotiated settlements (the #1 expense for liability insurers), the tort litigation environment is arguably a core driver of the pricing and cost structure of the carrier itself.

The challenge for insurers is that they only see their slice of the litigation data, commensurate with their market share, which for the average insurer is 1% or less. In contrast, our industry-wide database gives us an unprecedented understanding of the litigation environment to understand the BATNA, including how it is affected by specific venues and attorneys.

To better understand whether and how trial verdicts have changed in the post-COVID period, we analyzed 11,000 validated plaintiff tort verdicts in our database. This article summarizes our findings and discusses implications for both understanding the BATNA and trial selection at a tactical, actionable level.

Pre- and Post-COVID Verdict Analysis - Methodology

To better understand the litigation environments in the pre- and post-COVID timeframes, we analyzed 11,000 validated plaintiff verdicts in our database, broken into three distinct periods:

- Pre-COVID (2015-2019)

- COVID (2020-2021)

- Post-COVID (2022-2023)

We examined verdict size (both including and excluding punitive damages), as well as non-economic damages award levels across these time frames.

Our methodology included:

- The use of detailed actual jury verdict numbers

- A non-economic performance assessment using a machine learning model

- Rigorous bottoms-up analysis, controlled for inflation and other factors

The Relevance of Non-Economic Award Levels

We focus significantly on non-economic damages performance because it is one of the purest indicators, in our view, of the social inflation pressures that juries bring to bear. We all know what the economic damages are in a file; the unknown is what a jury might do with the non-economic award.

To maximize insight into non-economic performance, we use a machine learning model, as this enables us to account for changes in injury severity, plaintiff age, and a host of other factors. Using this model also enables us to isolate venue influences from individual attorney influences, and we think defense teams are stronger when they can distinguish between those two.

Data that shows which plaintiff attorneys are better at extracting higher non-economic awards, and which venues are more likely to give them, is critically important to understanding the BATNA on a specific case.

Our Most Important Finding: Granularity Matters

Our most important observation from this detailed analysis is that granularity matters. A lot.

Although we arrive at some sweeping conclusions about jury verdicts and non-economic performance in the post-COVID timeframe (see below), what stood out more for us was how granular the data needs to be to be helpful in understanding the litigation environment.

More specifically, two things are very clear:

- Geography matters

- The attorney matters

Just focusing on geography for a minute, our data shows that the most plaintiff-favorable large venue in Maryland (Prince George’s) is more favorable to the defense than the most defense-favorable large venue in the state of Connecticut (Hartford). This may be irrelevant to a litigation executive with all their files in Maryland, but it is highly relevant to an organization with litigated files in both places.

In the same vein, but within a single state, non-economic damages performance in Los Angeles County is significantly higher than San Diego and Orange Counties. These differences suggest that thinking about the case as being “in California” may be less helpful than understanding the litigation environment in each county.

On the plaintiff attorney front, we all know that specific attorneys are simply better at extracting high non-economic awards from juries than other attorneys. Understanding the specific verdict track records of these attorneys enables defense teams to quantify more accurately file-specific BATNAs. (As an aside, those track records can also be compared with the accomplishments that plaintiff attorneys list on their websites, which can be quite amusing).

See also: Insurance Industry Faces Major Changes in 2025

Example – 10 Large Counties

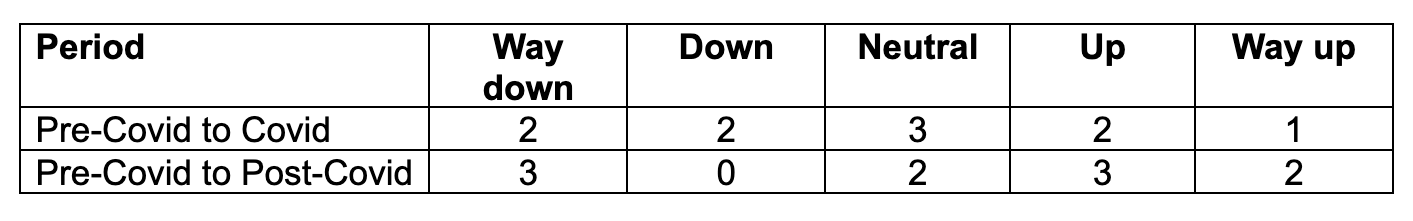

In our analysis we examined 10 large litigious counties nationally in our database and compared their non-economic model results.

The results emphasized for us how difficult (or at least unhelpful) it is to make sweeping generalizations about the COVID and post-COVID timeframes.

During the actual COVID period (2020-2021) itself, more of these 10 counties went down than up. In fact, two went “way down” while one went “way up.”

Key:

- Way down = more than 40%

- Down = between 15% and 40%

- Neutral = within 15%

- Up = between 15% and 40%

- Way up = more than 40%

Our point about the granularity is that, while overall non-economic performance has increased post-COVID, that may not be relevant to you if your case is in a jurisdiction where that performance has actually decreased.

Example – Texas and New York

Results were also mixed across counties within the same state. Texas demonstrated the most extremes. For two of the largest counties, one went way down while the other went way up.

Other states were not so extreme. Across the three largest counties in New York, one remained neutral, one went up, and one went way down. To say that “New York as a whole has gotten worse” would be inaccurate.

Example – Philadelphia County

Other venues have experienced dramatic changes in non-economic model performance. As an example, prior to COVID, Philadelphia County was somewhat favorable to the defense. During the pre-COVID period, this venue produced a -27% non-economic model result, meaning that it under-performed the machine learning model by 27%.

However, in the post-COVID period, Philadelphia County is at +75% and a scary place for the defense.

Findings: The Post-COVID Litigation Environment

With the important caveats listed above about the need to understand the litigation environment at a very granular level, the key findings produced during our analysis included:

Verdict Size

- With punitive damages excluded, average verdict sizes rose 28% during COVID and rose 179% from the pre-COVID period (2015-2019) to the post-COVID period (2022-2023), nearly tripling over that timeframe.

- Applying statistical methods to account for outliers, the values were 18% and 107%, respectively

- When punitive damages are included in the results, average verdict sizes have risen by 12% over the COVID timeframe and have increased by 274% when compared with the pre-COVID period.

The cause of this is mixed. From the pre-COVID to post-COVID period, there was both a rise in case severity (based on medical specials and injury severities) and a rise in non-economic damages performance

Non-Economic Performance

- Average non-economic performance has increased by 37% over the COVID timeframe and has increased by 40% when compared with the pre-Covid period.

- The state of Texas is responsible for about half of this increase. Average non-economic performance increased by a whopping 211% during COVID, only retracting slightly in the post-COVID period (2022-2023) for an overall rise of 165%. This was despite near-zero changes in medical specials or injury severity during the COVID and post-COVID periods. Again, this was not consistent across the state.

- Excluding Texas, average non-economic performance was flat during COVID and then increased by 21% post-COVID (2022-2023).

See also: Does the P&C Insurance Cycle No Longer Exist?

Moving from broad generalizations to actionable intelligence

Historically, we have tended to speak about the litigation environment at a macro level. We are inundated with bad news stories about runaway juries and detailed reports reminding us that nuclear verdicts are a growing problem. While this information is very important for highlighting generalized social trends and setting the stage for broader societal policy reform, it is less helpful to a defense team facing a trucking lawsuit in San Diego County.

From our vantage point, focusing only on the macro (nuclear verdicts) is having a chilling effect on our industry. We are taking fewer cases to trial, are paying more in settlements, and have been unable to diminish litigation costs. Attorney representation on pre-litigated files has skyrocketed.

On the other side of the battlefield, the plaintiff bar is investing heavily in technology to make itself even more effective. We have written before about EvenUp Law, a company that secured more than $220 million in investment in 18 months, has achieved unicorn status, and claims thousands of plaintiff firms as their clients. The use of data that maximizes trial and settlement amounts is attractive to the plaintiff bar, to say the least.

We believe it is time for the defense to do the same, and, in light of our findings, there is no question that the BATNAs we face across our litigation portfolios are changing.

For us, the more relevant question is a fundamental one about how we respond as an industry.

One option is to feel powerfulness and blame the problem on others, by saying that juries have gone crazy and the plaintiff bar is beating us. This option doesn’t accomplish much and simply becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. We cannot think of any litigation executive with whom we interact who finds this option attractive.

Option two is to respond to the plaintiff bar by taking a more data-driven plan of action that improves litigation outcomes. This option stems from the knowledge that a deep understanding of the litigation environment in which a case resides yields a better quantification of the true BATNA on the file. Further, it recognizes that our perception of the BATNA translates to values on pre-litigated files as well, and therefore has wide-ranging implications.

Litigation settlements involve “bargaining under the shadow of trial,” which requires an in-depth understanding of the BATNA (verdict risk), which requires an in-depth understanding of the litigation environment. As in other areas of insurance, values need to reflect risk, and to understand risk we need data.

Option two requires three things:

- Being highly granular in our litigation environment analysis

- Using detailed data about venue and geographic differences

- Leveraging a deep understanding of actual track record (instead of reputation), for both plaintiff attorneys and venues

These actions will help us to make more informed, data-driven, settlement decisions. They will help us to better understand which cases to try, and to make higher-quality decisions overall.

Said another way, they will help us to reclaim our BATNAs.