The 2023 North Atlantic hurricane season got off to an unusually early start, with an unnamed subtropical storm off the north-eastern coast of the U.S. in January – well before the hurricane season’s official start date of June 1.

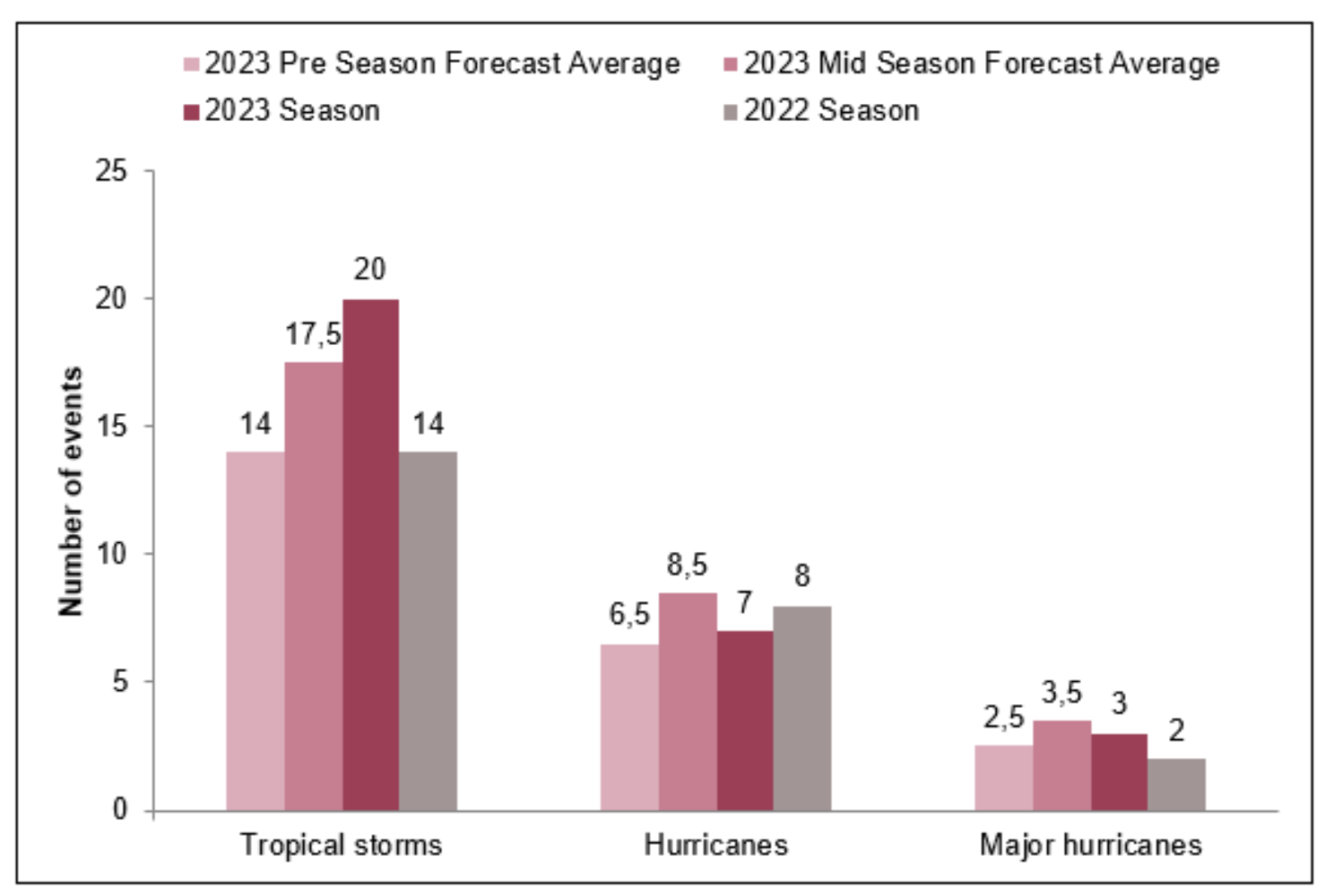

By Nov. 23, the 2023 season had witnessed 20 named storms, six more than the average pre-season forecasts expected. 2023 had the fourth-highest total of named storms in a year since 1950, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Of these, seven intensified into hurricanes, with three escalating to major hurricane status: Lee (Category 5), Franklin (Category 4) and Idalia (a Category 4 hurricane that was Category 3 upon landfall).

A season of “fish storms”?

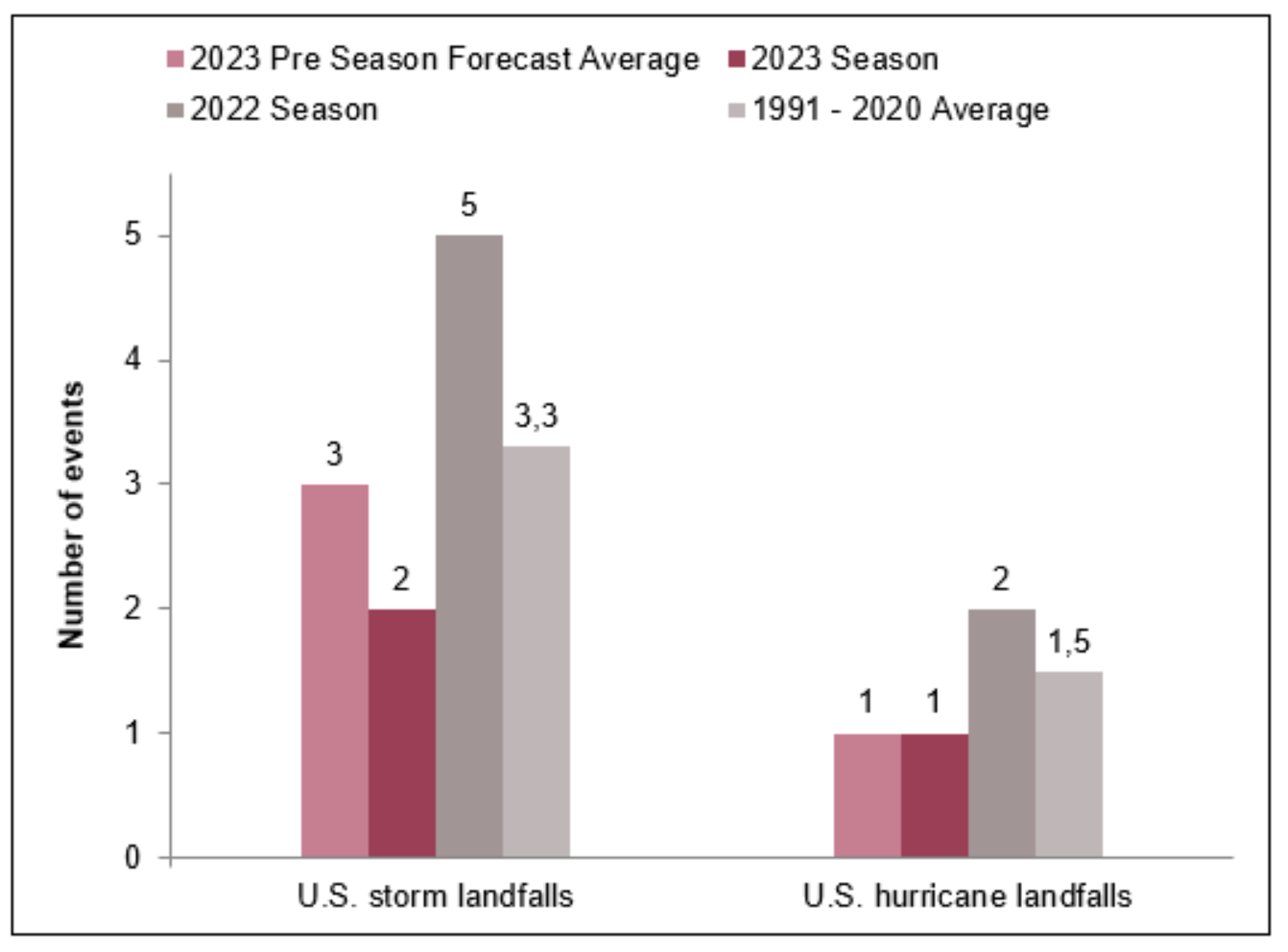

Only eight storms have made landfall so far in 2023, and only tropical storms Harold and Ophelia and Hurricane Idalia made landfall in the U.S. This has led to most storms being referred to as “fish storms” – storms that pose virtually no risk to land but can be a threat to boats and ships and produce dangerous currents along the coast.

Hurricane Franklin was the first major hurricane of the 2023 Atlantic hurricane season. It made landfall as a tropical storm on the southern coast of the Dominican Republic and triggered heavy rainfall and destructive winds. After passing the Dominican Republic, it intensified into a Category 4 hurricane on the high seas.

In late August, Hurricane Idalia made landfall in Florida’s Big Bend region (where the narrow Florida Panhandle merges into the wider Florida peninsula) as a Category 3 storm, becoming the first major hurricane to make landfall in that area since record-keeping began in 1842.

At peak season in early September, the massive and expansive Category 1 Hurricane Lee threatened to hit the eastern coast of the U.S. and Canada. A long-lived storm, Lee underwent a remarkable transformation, intensifying from a Category 1 to a Category 5 storm in just 24 hours. However, it quickly weakened and became an extratropical storm before making landfall in Nova Scotia as a Category 1 storm, then moving out into the far northern Atlantic.

Lee’s extratropical phase brought rain and gale-force winds to parts of the U.K. and Ireland. Meanwhile, swells generated by the storm triggered dangerous surf and rip currents along the entire Atlantic coast of the U.S. Aon estimates economic losses due to Hurricane Lee to be around $50 million.

See also: Key Learnings From Winter Storms

How did the 2023 season compare with the forecasts?

Contrary to pre-season predictions of a near-average season, the 2023 Atlantic hurricane season turned out to be above average, with Hurricane Idalia making it to the list of costliest Atlantic hurricanes in recorded history.

El Niño, a natural climate pattern associated with warmer-than-average sea surface temperatures (SSTs) in the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean, typically casts a dampening effect on Atlantic hurricane activity. This is because El Niño can increase wind shear, a disruptive force that can hinder hurricane formation and intensification. However, the 2023 Atlantic hurricane season has defied this El Niño-induced suppression, producing an unusually high number of named storms. This can be attributed to exceptionally warm SST anomalies recorded in the north Atlantic Ocean. These record-breaking SSTs were caused by a combination of short-term anomalous circulation in the atmosphere and longer-term changes in the ocean.

The complex interplay of these contrasting climate signals made it difficult for forecasters to accurately predict the activity of the 2023 hurricane season. Forecasting institutions were faced with the challenge of balancing the typically hurricane-suppressing effects of El Niño with the potent hurricane-fueling conditions created by the warm Atlantic waters.

Midway through the season, forecasting bodies such as the NOAA and National Hurricane Center revised their predictions, indicating that the season would be more active than previously anticipated.

Comparison of the 2023 North Atlantic hurricane season storms to the pre-season forecast averages, mid-season averages of AccuWeather, Colorado State University (CSU), Tropical Storm Risk (TSR), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and North Carolina State University (NCSU) and 2022 season actuals.

Source data: National Hurricane Center. Graphics by Allianz Commercial

Deep dive: Hurricane Idalia

On Aug. 30, Hurricane Idalia made landfall along the Florida coast, unleashing its fury on the Big Bend region. The system briefly attained a Category 4 status on its approach to Florida, but its intensity waned to maximum sustained wind speeds of 201km/h (125 mph) before it made a destructive landfall as a Category 3 hurricane near Keaton Beach, Florida. Despite a gradual weakening after landfall, Idalia’s initial intensity and rapid forward speed propelled it across northern Florida and into southern Georgia within a mere nine hours, maintaining hurricane strength throughout its path.

Idalia unleashed catastrophic storm surges with inundation levels in coastal areas ranging from 2 to 3.7 meters (7 to 12 feet). These surges were among the highest recorded since the 1993 Storm of the Century, leaving a trail of destruction along the coast.

Heavy rainfall also accompanied Idalia, leading to flash flooding in some areas. The storm’s impact extended beyond Florida, with heavy rainfall and strong winds affecting Georgia. As Idalia weakened further, it continued into southern South Carolina, where it still posed a significant threat as a tropical storm.

Moody’s RMS estimates insured losses from Hurricane Idalia to range between $3 billion and $5 billion, with a best estimate of $3.5 billion. Additionally, Moody’s RMS anticipates the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) could incur losses of around $500million. It expects the U.S. private market insured losses to be driven by wind, while storm surge and flood could contribute to around 40% of total private market losses and around 30% of the total event losses (including NFIP). Moody's RMS estimates most private market insured losses (around 70%) and NFIP losses (around 90% to 95%) from Idalia to be in Florida.

Even though losses from Idalia surpassed the billion-dollar mark, two factors may have helped mitigate its impact. First, the landfall area has a significantly lower population and exposure density compared with much of Florida. Second, Idalia had a relatively small wind field, which helped reduce the spatial extent of wind-induced damages. However, some of this mitigation was counteracted by the greater vulnerability of the properties in the region, which were mostly built during the 1980s and 1990s, before modern building codes were implemented.

See also: Glimmers of Good News on Climate (Finally)

Where are we now?

The Atlantic hurricane season has officially ended (on Nov. 30), having had notable impacts on several regions. The impact of Hurricane Idalia, particularly its storm surge and floods (both pluvial and fluvial), underscores the urgent need to accurately model and incorporate secondary perils into probabilistic catastrophe models. The increasing relevance of these perils due to climate change necessitates further research and development in secondary peril modeling to fully assess and mitigate disaster risks. While advancements in these models have been significant, adequately capturing the complexity and potential impact of secondary perils remains a challenge.

The information within this article is based on the preliminary operational data and tropical cyclone reports available on various sources as of Nov. 23, 2023. Tropical cyclone reports for several storms have yet to be released and may adjust storm parameters based on reanalysis.