You may be old enough to remember that bond investments suffered meaningfully in the late 1970s as inflationary pressures rose unabated. We are not expecting a replay of that environment, but the potential for rising inflationary expectations in a generational low-interest-rate environment is not a positive for what many consider “safe” bond investments. Quite the opposite.

As we have discussed previously, total debt outstanding globally has grown very meaningfully since 2009. In this cycle, it is the governments that have been the credit expansion provocateurs via the issuance of bonds. In the U.S. alone, government debt has more than doubled from $8 trillion to more than $18.5 trillion since 2009. We have seen like circumstances in Japan, China and part of Europe. Globally, government debt has grown close to $40 trillion since 2009. It is investors and in part central banks that have purchased these bonds. What has allowed this to occur without consequence so far has been the fact that central banks have held interest rates at artificially low levels.

Although debt levels have surged, interest cost in 2014 was not much higher than we saw in 2007, 2008 and 2011. Of course, this was accomplished by the U.S. Fed dropping interest rates to zero. The U.S. has been able to issue one-year Treasury bonds at a cost of 0.1% for a number of years. 0% interest rates in many global markets have allowed governments to borrow more both to pay off old loans and finance continued expanding deficits. In late 2007, the yield on 10-year U.S. Treasuries was 4-5%. In mid-2012, it briefly dropped below 1.5%.

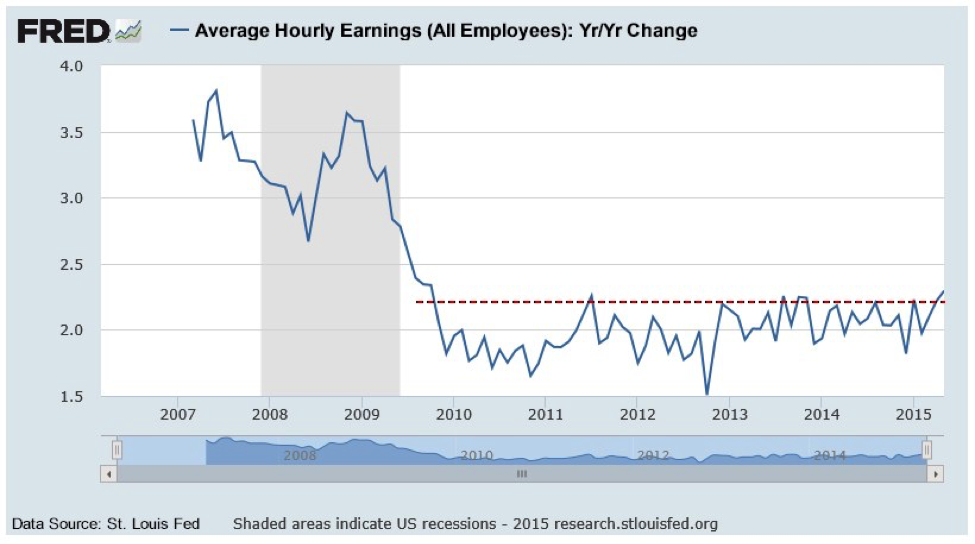

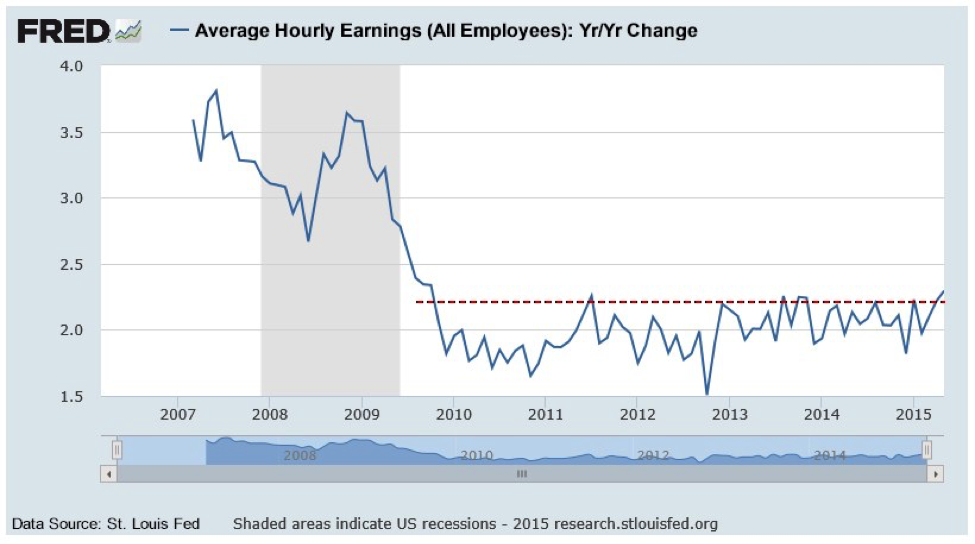

So here is the issue to be faced in the U.S., and we can assure you that conceptually identical circumstances exist in Japan, China and Europe. At the moment, the total cost of U.S. Government debt outstanding is approximately 2.2%. This number comes directly from the U.S. Treasury website and is documented monthly. At that level of debt cost, the U.S. paid approximately $500 billion in interest last year. In a rising-interest-rate environment, this number goes up. At just 4%, our interest costs alone would approach $1 trillion -- at 6%, probably $1.4 trillion in interest-only costs. It’s no wonder the Fed has been so reluctant to raise rates. Conceptually, as interest rates move higher, government balance sheets globally will deteriorate in quality (higher interest costs). Bond investors need to be fully aware of and monitoring this set of circumstances. Remember, we have not even discussed the enormity of off-balance-sheet government liabilities/commitments such as Social Security costs and exponential Medicare funding to come. Again, governments globally face very similar debt and social cost spirals. The “quality” of their balance sheets will be tested somewhere ahead.

Our final issue of current consideration for bond investors is one of global investment concentration risk. Just what has happened to all of the debt issued by governments and corporations (using the proceeds to repurchase stock) in the current cycle? It has ended up in bond investment pools. It has been purchased by investment funds, pension funds, the retail public, etc. Don Coxe of Coxe Advisors (long-tenured on Wall Street and an analyst we respect) recently reported that 70% of total bonds outstanding on planet Earth are held by 20 investment companies. Think the very large bond houses like PIMCO, Blackrock, etc. These pools are incredibly large in terms of dollar magnitude. You can see the punchline coming, can’t you?

If these large pools ever needed to (or were instructed to by their investors) sell to preserve capital, sell to whom becomes the question? These are behemoth holders that need a behemoth buyer. And as is typical of human behavior, it’s a very high probability a number of these funds would be looking to sell or lighten up at exactly the same time. Wall Street runs in herds. The massive concentration risk in global bond holdings is a key watch point for bond investors that we believe is underappreciated.

Is the world coming to an end for bond investors? Not at all. What is most important is to understand that, in the current market cycle, bonds are not the safe haven investments they have traditionally been in cycles of the last three-plus decades. Quite the opposite. Investment risk in current bond investments is real and must be managed. Most investors in today’s market have no experience in managing through a bond bear market. That will change before the current cycle has ended. As always, having a plan of action for anticipated market outcomes (whether they ever materialize) is the key to overall investment risk management.

You may be old enough to remember that bond investments suffered meaningfully in the late 1970s as inflationary pressures rose unabated. We are not expecting a replay of that environment, but the potential for rising inflationary expectations in a generational low-interest-rate environment is not a positive for what many consider “safe” bond investments. Quite the opposite.

As we have discussed previously, total debt outstanding globally has grown very meaningfully since 2009. In this cycle, it is the governments that have been the credit expansion provocateurs via the issuance of bonds. In the U.S. alone, government debt has more than doubled from $8 trillion to more than $18.5 trillion since 2009. We have seen like circumstances in Japan, China and part of Europe. Globally, government debt has grown close to $40 trillion since 2009. It is investors and in part central banks that have purchased these bonds. What has allowed this to occur without consequence so far has been the fact that central banks have held interest rates at artificially low levels.

Although debt levels have surged, interest cost in 2014 was not much higher than we saw in 2007, 2008 and 2011. Of course, this was accomplished by the U.S. Fed dropping interest rates to zero. The U.S. has been able to issue one-year Treasury bonds at a cost of 0.1% for a number of years. 0% interest rates in many global markets have allowed governments to borrow more both to pay off old loans and finance continued expanding deficits. In late 2007, the yield on 10-year U.S. Treasuries was 4-5%. In mid-2012, it briefly dropped below 1.5%.

So here is the issue to be faced in the U.S., and we can assure you that conceptually identical circumstances exist in Japan, China and Europe. At the moment, the total cost of U.S. Government debt outstanding is approximately 2.2%. This number comes directly from the U.S. Treasury website and is documented monthly. At that level of debt cost, the U.S. paid approximately $500 billion in interest last year. In a rising-interest-rate environment, this number goes up. At just 4%, our interest costs alone would approach $1 trillion -- at 6%, probably $1.4 trillion in interest-only costs. It’s no wonder the Fed has been so reluctant to raise rates. Conceptually, as interest rates move higher, government balance sheets globally will deteriorate in quality (higher interest costs). Bond investors need to be fully aware of and monitoring this set of circumstances. Remember, we have not even discussed the enormity of off-balance-sheet government liabilities/commitments such as Social Security costs and exponential Medicare funding to come. Again, governments globally face very similar debt and social cost spirals. The “quality” of their balance sheets will be tested somewhere ahead.

Our final issue of current consideration for bond investors is one of global investment concentration risk. Just what has happened to all of the debt issued by governments and corporations (using the proceeds to repurchase stock) in the current cycle? It has ended up in bond investment pools. It has been purchased by investment funds, pension funds, the retail public, etc. Don Coxe of Coxe Advisors (long-tenured on Wall Street and an analyst we respect) recently reported that 70% of total bonds outstanding on planet Earth are held by 20 investment companies. Think the very large bond houses like PIMCO, Blackrock, etc. These pools are incredibly large in terms of dollar magnitude. You can see the punchline coming, can’t you?

If these large pools ever needed to (or were instructed to by their investors) sell to preserve capital, sell to whom becomes the question? These are behemoth holders that need a behemoth buyer. And as is typical of human behavior, it’s a very high probability a number of these funds would be looking to sell or lighten up at exactly the same time. Wall Street runs in herds. The massive concentration risk in global bond holdings is a key watch point for bond investors that we believe is underappreciated.

Is the world coming to an end for bond investors? Not at all. What is most important is to understand that, in the current market cycle, bonds are not the safe haven investments they have traditionally been in cycles of the last three-plus decades. Quite the opposite. Investment risk in current bond investments is real and must be managed. Most investors in today’s market have no experience in managing through a bond bear market. That will change before the current cycle has ended. As always, having a plan of action for anticipated market outcomes (whether they ever materialize) is the key to overall investment risk management.Bonds Away: Market Faces Major Shift

Bonds, long a safe haven for investors, will not be for long, as interest rates rise and government issuers and mega-buyers face new risks.

You may be old enough to remember that bond investments suffered meaningfully in the late 1970s as inflationary pressures rose unabated. We are not expecting a replay of that environment, but the potential for rising inflationary expectations in a generational low-interest-rate environment is not a positive for what many consider “safe” bond investments. Quite the opposite.

As we have discussed previously, total debt outstanding globally has grown very meaningfully since 2009. In this cycle, it is the governments that have been the credit expansion provocateurs via the issuance of bonds. In the U.S. alone, government debt has more than doubled from $8 trillion to more than $18.5 trillion since 2009. We have seen like circumstances in Japan, China and part of Europe. Globally, government debt has grown close to $40 trillion since 2009. It is investors and in part central banks that have purchased these bonds. What has allowed this to occur without consequence so far has been the fact that central banks have held interest rates at artificially low levels.

Although debt levels have surged, interest cost in 2014 was not much higher than we saw in 2007, 2008 and 2011. Of course, this was accomplished by the U.S. Fed dropping interest rates to zero. The U.S. has been able to issue one-year Treasury bonds at a cost of 0.1% for a number of years. 0% interest rates in many global markets have allowed governments to borrow more both to pay off old loans and finance continued expanding deficits. In late 2007, the yield on 10-year U.S. Treasuries was 4-5%. In mid-2012, it briefly dropped below 1.5%.

So here is the issue to be faced in the U.S., and we can assure you that conceptually identical circumstances exist in Japan, China and Europe. At the moment, the total cost of U.S. Government debt outstanding is approximately 2.2%. This number comes directly from the U.S. Treasury website and is documented monthly. At that level of debt cost, the U.S. paid approximately $500 billion in interest last year. In a rising-interest-rate environment, this number goes up. At just 4%, our interest costs alone would approach $1 trillion -- at 6%, probably $1.4 trillion in interest-only costs. It’s no wonder the Fed has been so reluctant to raise rates. Conceptually, as interest rates move higher, government balance sheets globally will deteriorate in quality (higher interest costs). Bond investors need to be fully aware of and monitoring this set of circumstances. Remember, we have not even discussed the enormity of off-balance-sheet government liabilities/commitments such as Social Security costs and exponential Medicare funding to come. Again, governments globally face very similar debt and social cost spirals. The “quality” of their balance sheets will be tested somewhere ahead.

Our final issue of current consideration for bond investors is one of global investment concentration risk. Just what has happened to all of the debt issued by governments and corporations (using the proceeds to repurchase stock) in the current cycle? It has ended up in bond investment pools. It has been purchased by investment funds, pension funds, the retail public, etc. Don Coxe of Coxe Advisors (long-tenured on Wall Street and an analyst we respect) recently reported that 70% of total bonds outstanding on planet Earth are held by 20 investment companies. Think the very large bond houses like PIMCO, Blackrock, etc. These pools are incredibly large in terms of dollar magnitude. You can see the punchline coming, can’t you?

If these large pools ever needed to (or were instructed to by their investors) sell to preserve capital, sell to whom becomes the question? These are behemoth holders that need a behemoth buyer. And as is typical of human behavior, it’s a very high probability a number of these funds would be looking to sell or lighten up at exactly the same time. Wall Street runs in herds. The massive concentration risk in global bond holdings is a key watch point for bond investors that we believe is underappreciated.

Is the world coming to an end for bond investors? Not at all. What is most important is to understand that, in the current market cycle, bonds are not the safe haven investments they have traditionally been in cycles of the last three-plus decades. Quite the opposite. Investment risk in current bond investments is real and must be managed. Most investors in today’s market have no experience in managing through a bond bear market. That will change before the current cycle has ended. As always, having a plan of action for anticipated market outcomes (whether they ever materialize) is the key to overall investment risk management.

You may be old enough to remember that bond investments suffered meaningfully in the late 1970s as inflationary pressures rose unabated. We are not expecting a replay of that environment, but the potential for rising inflationary expectations in a generational low-interest-rate environment is not a positive for what many consider “safe” bond investments. Quite the opposite.

As we have discussed previously, total debt outstanding globally has grown very meaningfully since 2009. In this cycle, it is the governments that have been the credit expansion provocateurs via the issuance of bonds. In the U.S. alone, government debt has more than doubled from $8 trillion to more than $18.5 trillion since 2009. We have seen like circumstances in Japan, China and part of Europe. Globally, government debt has grown close to $40 trillion since 2009. It is investors and in part central banks that have purchased these bonds. What has allowed this to occur without consequence so far has been the fact that central banks have held interest rates at artificially low levels.

Although debt levels have surged, interest cost in 2014 was not much higher than we saw in 2007, 2008 and 2011. Of course, this was accomplished by the U.S. Fed dropping interest rates to zero. The U.S. has been able to issue one-year Treasury bonds at a cost of 0.1% for a number of years. 0% interest rates in many global markets have allowed governments to borrow more both to pay off old loans and finance continued expanding deficits. In late 2007, the yield on 10-year U.S. Treasuries was 4-5%. In mid-2012, it briefly dropped below 1.5%.

So here is the issue to be faced in the U.S., and we can assure you that conceptually identical circumstances exist in Japan, China and Europe. At the moment, the total cost of U.S. Government debt outstanding is approximately 2.2%. This number comes directly from the U.S. Treasury website and is documented monthly. At that level of debt cost, the U.S. paid approximately $500 billion in interest last year. In a rising-interest-rate environment, this number goes up. At just 4%, our interest costs alone would approach $1 trillion -- at 6%, probably $1.4 trillion in interest-only costs. It’s no wonder the Fed has been so reluctant to raise rates. Conceptually, as interest rates move higher, government balance sheets globally will deteriorate in quality (higher interest costs). Bond investors need to be fully aware of and monitoring this set of circumstances. Remember, we have not even discussed the enormity of off-balance-sheet government liabilities/commitments such as Social Security costs and exponential Medicare funding to come. Again, governments globally face very similar debt and social cost spirals. The “quality” of their balance sheets will be tested somewhere ahead.

Our final issue of current consideration for bond investors is one of global investment concentration risk. Just what has happened to all of the debt issued by governments and corporations (using the proceeds to repurchase stock) in the current cycle? It has ended up in bond investment pools. It has been purchased by investment funds, pension funds, the retail public, etc. Don Coxe of Coxe Advisors (long-tenured on Wall Street and an analyst we respect) recently reported that 70% of total bonds outstanding on planet Earth are held by 20 investment companies. Think the very large bond houses like PIMCO, Blackrock, etc. These pools are incredibly large in terms of dollar magnitude. You can see the punchline coming, can’t you?

If these large pools ever needed to (or were instructed to by their investors) sell to preserve capital, sell to whom becomes the question? These are behemoth holders that need a behemoth buyer. And as is typical of human behavior, it’s a very high probability a number of these funds would be looking to sell or lighten up at exactly the same time. Wall Street runs in herds. The massive concentration risk in global bond holdings is a key watch point for bond investors that we believe is underappreciated.

Is the world coming to an end for bond investors? Not at all. What is most important is to understand that, in the current market cycle, bonds are not the safe haven investments they have traditionally been in cycles of the last three-plus decades. Quite the opposite. Investment risk in current bond investments is real and must be managed. Most investors in today’s market have no experience in managing through a bond bear market. That will change before the current cycle has ended. As always, having a plan of action for anticipated market outcomes (whether they ever materialize) is the key to overall investment risk management.