This is Paper 4 in a series of five on risk appetite and associated questions. The author believes that enterprise risk management (ERM) will remain locked in organizational silos until boards comprehend the links between risk and strategy. This is achieved either through painful crises or through the less expensive development of a risk appetite framework (RAF). Understanding of risk appetite is in our view very much a work in progress for many organizations, but RAF development and approval can lead boards to demand action from executives.

Paper 1, the shortest paper, makes a number of general observations based on experience in working with a wide variety of companies.

Paper 2 describes the risk landscape, measurable and unmeasurable uncertainties and the evolution of risk management.

Paper 3 answers questions relating to the need for risk appetite frameworks and describes in some detail the relationship between risk appetite frameworks and strategy. This article, Paper 4, answers further questions on risk appetite and goes into some detail on the questions of risk culture and risk maturity. Paper 5 describes the characteristics of a risk appetite statement and provides a detailed summary of how to operate based on the links between risk and strategy.

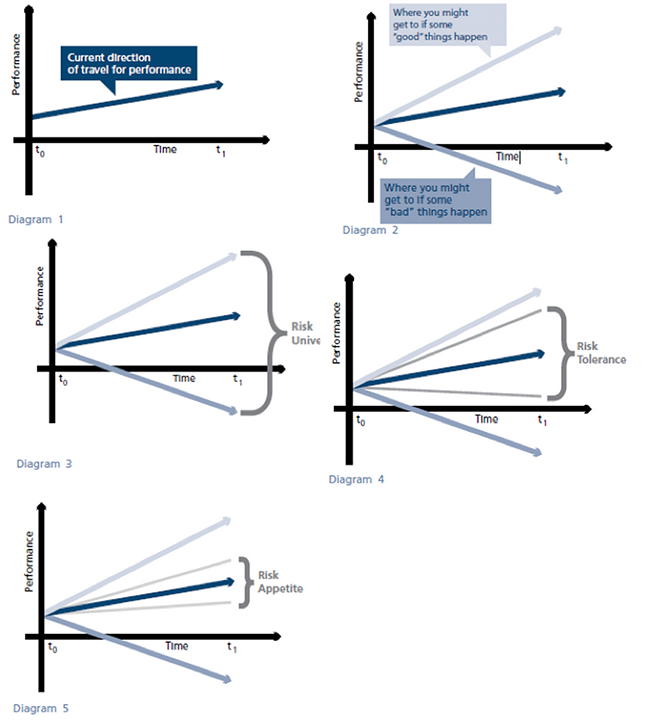

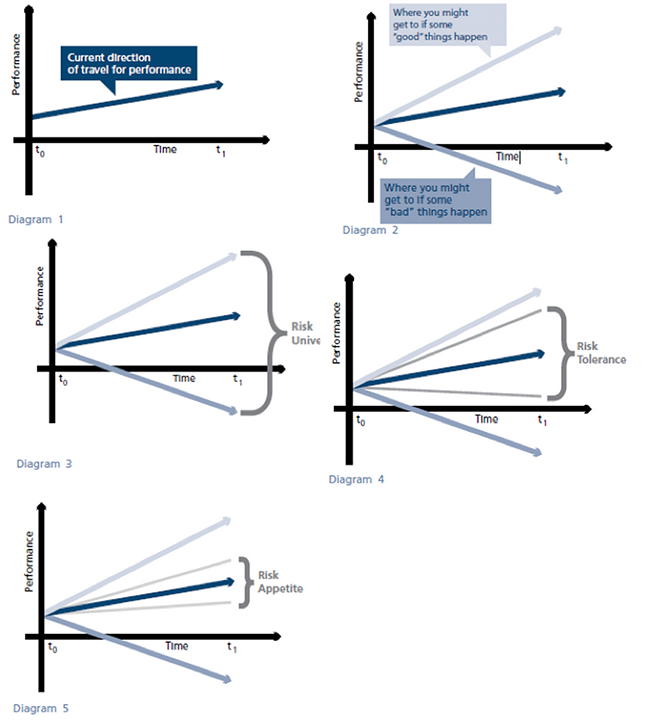

How are risk appetite, risk tolerance and risk limits related to one another? A range of differences in philosophy are influencing the gradual determination of internationally accepted definitions. Notwithstanding, we recommend the definitions and the sequence of diagrams and explanations given in

the Institute of Risk Management’s (IRM) guidance, which are

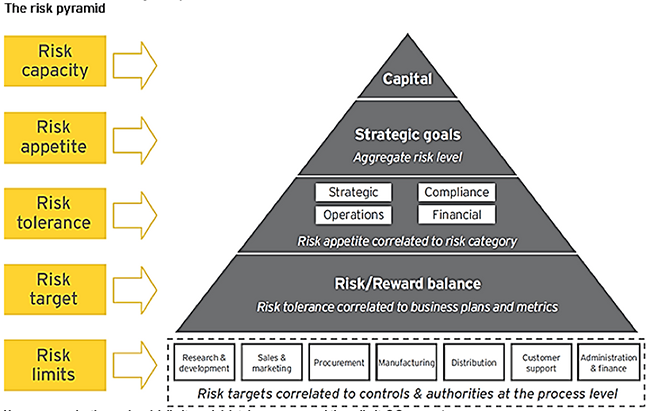

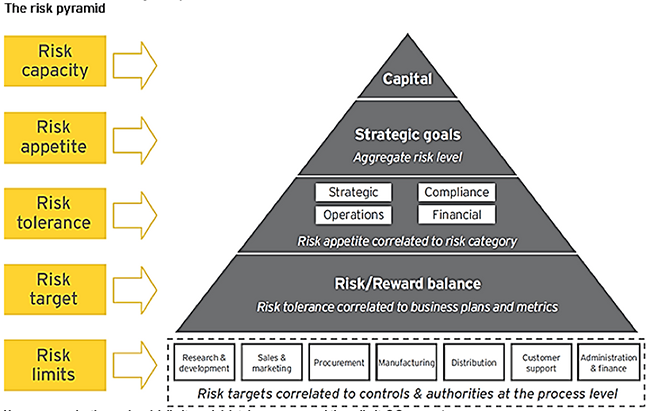

A number of models exist that seek to describe the relationship between risk appetite, tolerance and risk; for instance, the Ernest and Young Risk Pyramid below:

How are organizations using risk limits and risk tolerances around those limits?

How are organizations using risk limits and risk tolerances around those limits? Our experience in working with clients shows that organizations are continuing to struggle with basic risk concepts, definitions, language, responsibilities, reporting and delivery. Accordingly, while risk limits are set to contain risk-taking practices, lack of common language and loose interpretation of concepts is causing confusion within organizations and leading to limits being seen as negotiable within the context of risk tolerances. As a corporate discipline, risk management is in its infancy, and the quality of risk practitioners is generally poor. Risk limits are perceived negatively by business practitioners, who use their limited knowledge of risk tolerances to argue for greater flexibility in applying limits.

How do organizations facilitate early warning of potential breaches of risk appetite? In practice, we find that there is limited facilitation. Rather, business people see the concept of risk as limiting practices that drive value and, thus, adopt the business school mantra of "seeking forgiveness rather than permission." This is made easier in organizations where risk is seen as a nuisance and impediment to business and where appreciation of quality risk management is not apparent at senior levels. Business generators tend to view risk as friendly and flexible, designed to support business generation. Thus, risk limits are treated like speed limits on the public highway, more for observation than observance. Accordingly, we find few cases where early warnings are seen as anything other than flashing lights on the dashboard. In many cases, early warnings result in a case's being presented to the risk committee for raising limits, rather than resulting in severe braking to ensure conformity in risk management.

Much of the foregoing represents the cultural challenge of embedding risk as a serious discipline rather than a

faux science treated as an add-on. This reflects the nascent nature of risk management and its failure to be seen at board level as front and central to strategy and its effective and safe execution. Culture and "tone from the top" are critical here. So is strong support for risk executives at senior management level and an appreciation that risk management is akin to the medical profession, where hygiene is embedded in all procedures and provides a safe and secure means of conducting business, rather than being an impediment. The absence of good-quality risk officers and of universally accepted definitions of risk also undermine the discipline in organizations where there are few effective sanctions against limits being broken.

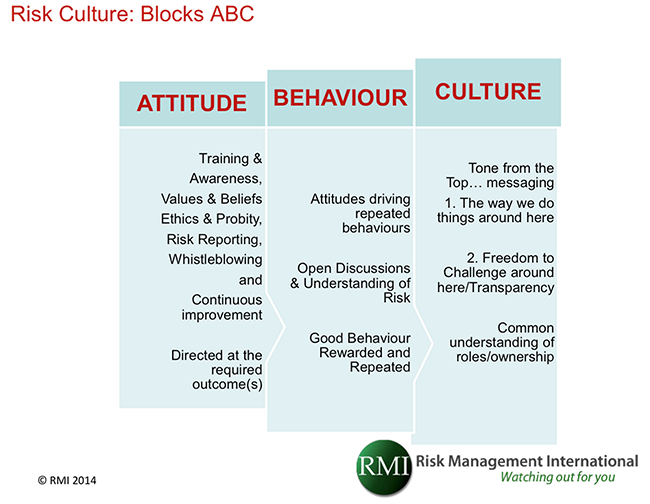

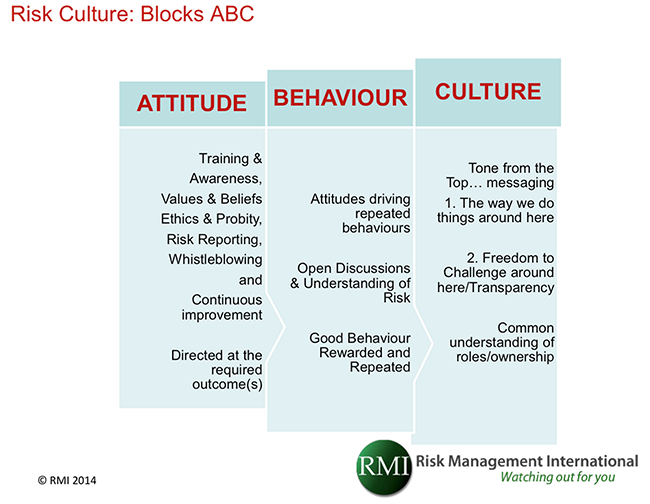

How do organizations assess risk culture? Optimal risk culture is designed and nurtured on building blocks practically described as blocks ABC:

The building blocks are briefly summarized as follows:

- Training, values and beliefs, reporting and continuous improvement directed at outcomes driving attitudes displayed by people, which

- Influence their behaviors and thus the quality of their discussions and decision making, thereby

- Manifesting as demonstrably credible risk culture.

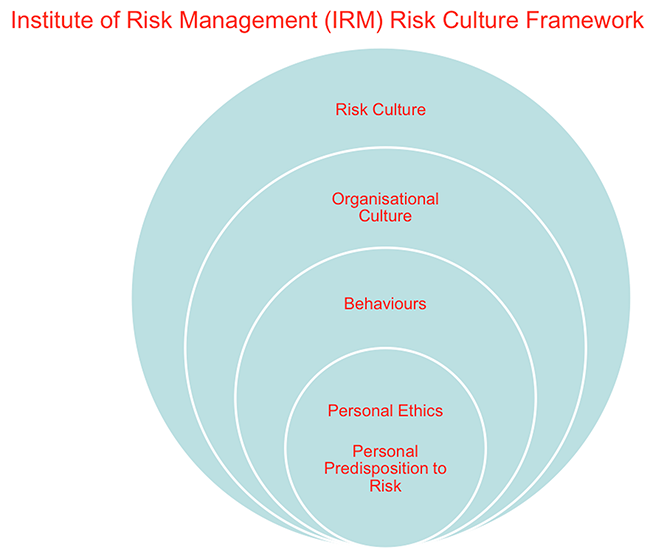

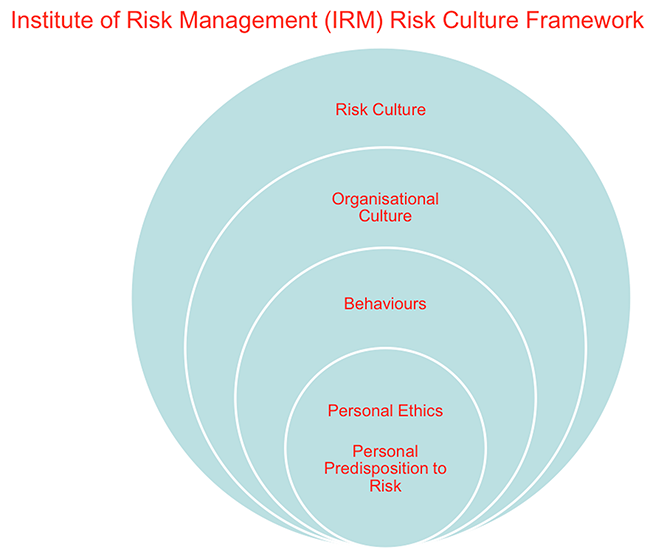

Other than retrospective analysis of poor risk culture following various corporate crises, there is a limited body of reliable knowledge, and experience, on assessing "existing risk culture" and successfully navigating to a "target risk culture." The IRM's "Risk Culture, Under the Microscope: Guidance for Boards" describes multiple interactions:

Diagnostic tools are available to track the components described within the framework above. In our experience, however, such is the poor state of risk maturity in very many organizations that they are not sufficiently advanced to practically determine how they might chart a course from the existing to the target state of risk culture.

Diagnostic tools are available to track the components described within the framework above. In our experience, however, such is the poor state of risk maturity in very many organizations that they are not sufficiently advanced to practically determine how they might chart a course from the existing to the target state of risk culture.

In 2011, the Financial Reporting Council produced the report: "Boards and Risk: A Summary of Discussions with Companies, Investors and Advisors." In the section on risk and control culture, the report said:

- It was recognized that risk and control culture was one of the issues on which it was most difficult for boards to get assurance, although boards appeared to be making more efforts to do so.

- The risk management and internal audit functions could play an important role, as could reports from and discussions with senior management, but some directors felt that there was no substitute for going on to the shop floor and seeing for themselves. It was otherwise very difficult to judge whether risk awareness was truly embedded or whether it was seen as a compliance exercise. This, in turn, assumed that non-executive directors had a sufficient understanding of the business, which some participants noted may not always be the case.

- One common approach was to ensure that responsibility for managing specific risks was clearly allocated to individuals at all levels of the organization, with their performance measured and reflected in how they were rewarded.

- In some companies, the remuneration committee had been given responsibility for considering how to align the company’s approach to risk and control with its remuneration and incentives. Examples were also given of the head of the risk management or internal audit function submitting reports to that committee, for example on how the company was performing against certain key risks, or being invited to comment on the details of proposed incentive schemes. More recently, the Financial Stability Board (FSB) in its "Peer Review Report on Risk Governance," published in February 2013, identified ‘’business conduct’’ as a new risk category and said, "One of the key lessons from the crisis (GFC) was that reputational risk was severely underestimated; hence, there is more focus on business conduct and the suitability of products, e.g., the type of products sold and to whom they are sold. As the crisis showed, consumer products such as residential mortgage loans could become a source of financial instability.” In consulting and developing guidance for regulators, the FSB emphasizes the importance of risk culture as a principal influencer reducing the risk of misselling financial services products that can end up in the wrong hands with detrimental prospects for consumers in particular and society in general. Clearly, conduct risk is systemic, and inherently so when considered in the context of big data; that is to say, conduct risk is very unlikely to exist in isolation within an organization.

Separately, the FSB has articulated what it considers to be the foundation elements of a strong risk culture in its publications on risk governance, risk appetite and compensation. It has broken down the indicators into four parts, which need to be considered collectively and as mutually reinforcing. The four parts are:

- Tone from the top: The board of directors and senior managers are the starting point for setting the financial institution’s core values and risk culture, and their behavior must reflect the values being espoused. The leadership of the institution should systematically develop, monitor and assess the culture of the financial institution.

- Accountability: Successful risk management requires employees at all levels to understand the core values of the institution’s risk culture and its approach to risk, be capable of performing their prescribed roles and be aware that they are held accountable for their actions in relation to the institution’s risk-taking behavior. Staff acceptance of risk-related goals and related values is seen as essential.

- Effective challenge: A sound risk culture promotes an environment of effective challenge in which decision-making processes promote a range of views, allow for testing of current practices and stimulate a positive, critical attitude among employees and an environment of open and constructive engagement.

- Incentives: Performance and talent management should encourage and reinforce maintenance of the financial institution’s desired risk management behavior. Financial and non-financial incentives should support the core values and risk culture at all levels of the financial institution.

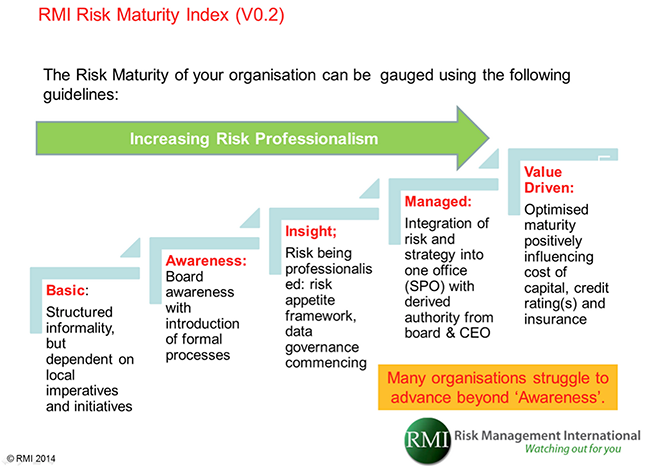

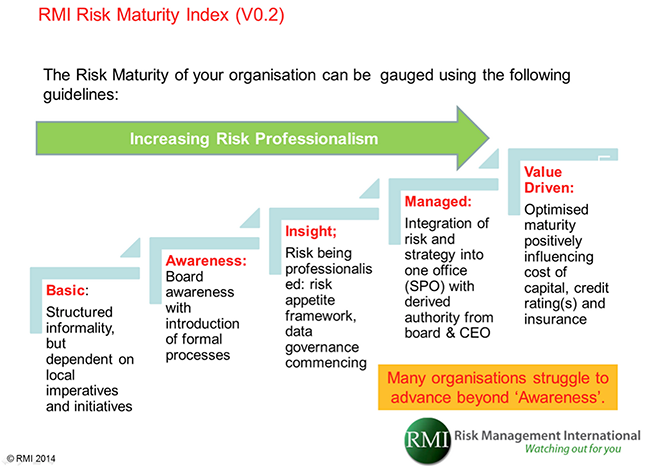

Clearly, there is consistency in thinking as to the importance of risk culture and its core attributes. Monitoring risk culture is, however, very challenging, indeed. To the particular question of communicating risk culture to stakeholders, we question whether this can be done credibly in the absence of finding proxies for attitudes and behaviors described in the ABC risk culture building blocks described above. Our experience tells us that risk maturity capability requirements are today well-understood, reliable and credible proxies for risk culture. On this basis, we recommend that organizations travel the better known road of "risk maturity," for which there are a number of capable maturity models in existence.

We believe there to be a demonstrably credible correlation between full maturity (optimizing value through aligning risk and strategy with corporate objectives) and board ownership of the risk appetite framework, building resilience (defending operations, business model and reputation) and risk culture. The RMI Risk Maturity Index correlates:

- Level of alignment of risks to strategy, objectives and execution,

- Risk role affirmations at each maturity level,

- Risk culture affirmations (practices confirmed by internal and external attestors),

- Risk defense affirmations (practices confirmed by internal and external attestors),

- Board and organizational processes, and

- Value realized at three levels: a) the investor, b) the organization and c) stakeholders.

Progression from one level to the next requires a blend of internal and external independent attestations, which are facilitated with the aid of a database containing structured question sets. Risk maturity scores are weighted according to the:

- Quality of answers provided to questions,

- Availability of demonstrably credible evidence supporting answers,

- Rigor and consistency of risk data,

We believe that risk maturity attestation by seasoned practitioners will provide evidence-based assurance as to organizational risk culture.

A number of models exist that seek to describe the relationship between risk appetite, tolerance and risk; for instance, the Ernest and Young Risk Pyramid below:

A number of models exist that seek to describe the relationship between risk appetite, tolerance and risk; for instance, the Ernest and Young Risk Pyramid below:

How are organizations using risk limits and risk tolerances around those limits? Our experience in working with clients shows that organizations are continuing to struggle with basic risk concepts, definitions, language, responsibilities, reporting and delivery. Accordingly, while risk limits are set to contain risk-taking practices, lack of common language and loose interpretation of concepts is causing confusion within organizations and leading to limits being seen as negotiable within the context of risk tolerances. As a corporate discipline, risk management is in its infancy, and the quality of risk practitioners is generally poor. Risk limits are perceived negatively by business practitioners, who use their limited knowledge of risk tolerances to argue for greater flexibility in applying limits.

How do organizations facilitate early warning of potential breaches of risk appetite? In practice, we find that there is limited facilitation. Rather, business people see the concept of risk as limiting practices that drive value and, thus, adopt the business school mantra of "seeking forgiveness rather than permission." This is made easier in organizations where risk is seen as a nuisance and impediment to business and where appreciation of quality risk management is not apparent at senior levels. Business generators tend to view risk as friendly and flexible, designed to support business generation. Thus, risk limits are treated like speed limits on the public highway, more for observation than observance. Accordingly, we find few cases where early warnings are seen as anything other than flashing lights on the dashboard. In many cases, early warnings result in a case's being presented to the risk committee for raising limits, rather than resulting in severe braking to ensure conformity in risk management.

Much of the foregoing represents the cultural challenge of embedding risk as a serious discipline rather than a faux science treated as an add-on. This reflects the nascent nature of risk management and its failure to be seen at board level as front and central to strategy and its effective and safe execution. Culture and "tone from the top" are critical here. So is strong support for risk executives at senior management level and an appreciation that risk management is akin to the medical profession, where hygiene is embedded in all procedures and provides a safe and secure means of conducting business, rather than being an impediment. The absence of good-quality risk officers and of universally accepted definitions of risk also undermine the discipline in organizations where there are few effective sanctions against limits being broken.

How do organizations assess risk culture? Optimal risk culture is designed and nurtured on building blocks practically described as blocks ABC:

How are organizations using risk limits and risk tolerances around those limits? Our experience in working with clients shows that organizations are continuing to struggle with basic risk concepts, definitions, language, responsibilities, reporting and delivery. Accordingly, while risk limits are set to contain risk-taking practices, lack of common language and loose interpretation of concepts is causing confusion within organizations and leading to limits being seen as negotiable within the context of risk tolerances. As a corporate discipline, risk management is in its infancy, and the quality of risk practitioners is generally poor. Risk limits are perceived negatively by business practitioners, who use their limited knowledge of risk tolerances to argue for greater flexibility in applying limits.

How do organizations facilitate early warning of potential breaches of risk appetite? In practice, we find that there is limited facilitation. Rather, business people see the concept of risk as limiting practices that drive value and, thus, adopt the business school mantra of "seeking forgiveness rather than permission." This is made easier in organizations where risk is seen as a nuisance and impediment to business and where appreciation of quality risk management is not apparent at senior levels. Business generators tend to view risk as friendly and flexible, designed to support business generation. Thus, risk limits are treated like speed limits on the public highway, more for observation than observance. Accordingly, we find few cases where early warnings are seen as anything other than flashing lights on the dashboard. In many cases, early warnings result in a case's being presented to the risk committee for raising limits, rather than resulting in severe braking to ensure conformity in risk management.

Much of the foregoing represents the cultural challenge of embedding risk as a serious discipline rather than a faux science treated as an add-on. This reflects the nascent nature of risk management and its failure to be seen at board level as front and central to strategy and its effective and safe execution. Culture and "tone from the top" are critical here. So is strong support for risk executives at senior management level and an appreciation that risk management is akin to the medical profession, where hygiene is embedded in all procedures and provides a safe and secure means of conducting business, rather than being an impediment. The absence of good-quality risk officers and of universally accepted definitions of risk also undermine the discipline in organizations where there are few effective sanctions against limits being broken.

How do organizations assess risk culture? Optimal risk culture is designed and nurtured on building blocks practically described as blocks ABC:

The building blocks are briefly summarized as follows:

The building blocks are briefly summarized as follows:

Diagnostic tools are available to track the components described within the framework above. In our experience, however, such is the poor state of risk maturity in very many organizations that they are not sufficiently advanced to practically determine how they might chart a course from the existing to the target state of risk culture.

Diagnostic tools are available to track the components described within the framework above. In our experience, however, such is the poor state of risk maturity in very many organizations that they are not sufficiently advanced to practically determine how they might chart a course from the existing to the target state of risk culture.

We believe there to be a demonstrably credible correlation between full maturity (optimizing value through aligning risk and strategy with corporate objectives) and board ownership of the risk appetite framework, building resilience (defending operations, business model and reputation) and risk culture. The RMI Risk Maturity Index correlates:

We believe there to be a demonstrably credible correlation between full maturity (optimizing value through aligning risk and strategy with corporate objectives) and board ownership of the risk appetite framework, building resilience (defending operations, business model and reputation) and risk culture. The RMI Risk Maturity Index correlates: