The recent cancellation of a major wind energy project off New Jersey's shore has cast a pall over efforts to limit climate change. But there are important signs of hope, too -- in particular, stunning declines in the cost of solar and wind power.

With the U.N.'s annual summit on climate set to start later this week, let's focus for a few minutes on the hope.

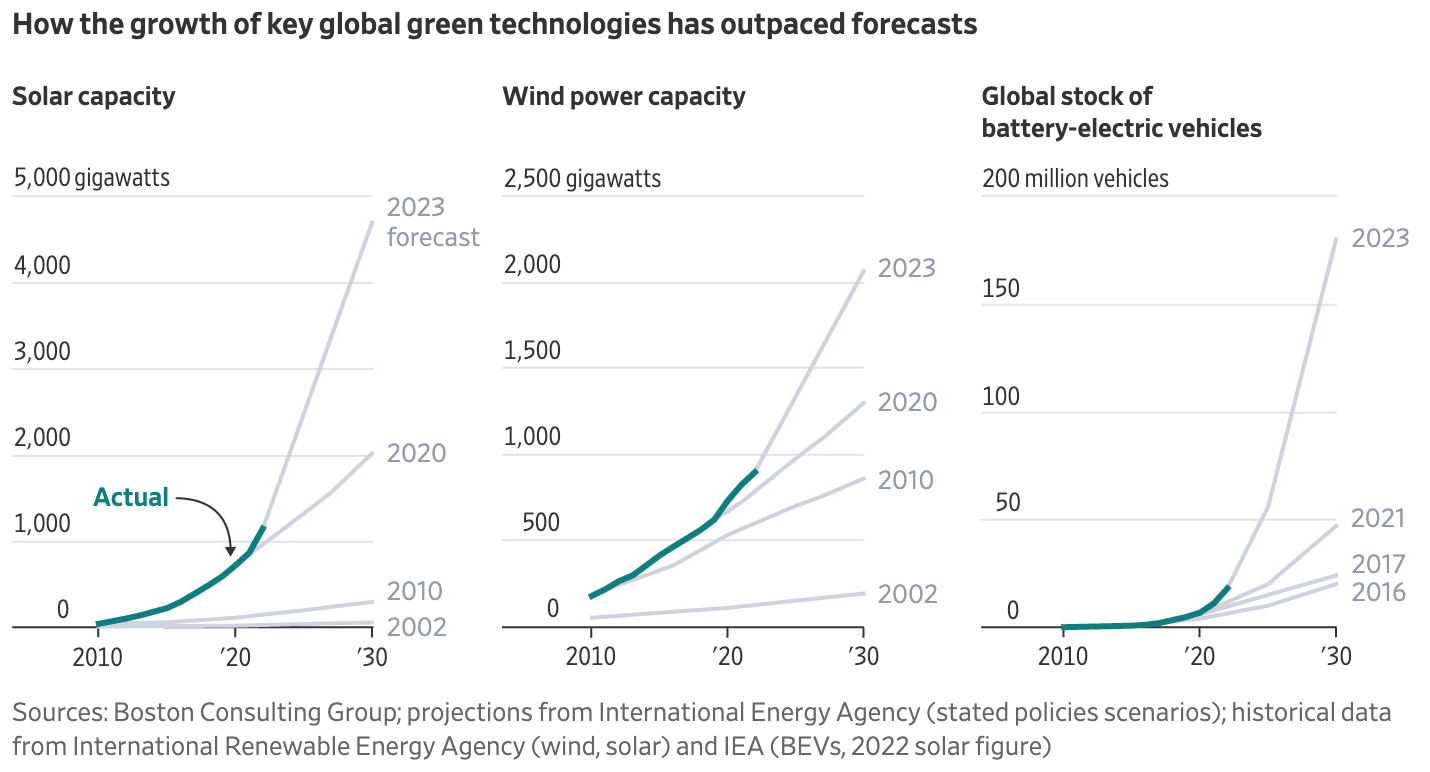

This chart from a recent article in the Wall Street Journal pretty much says it all:

You can see, in particular, how installations of solar power have consistently exceeded expectations -- by a lot. The 2002 projection the WSJ cites showed almost no adoption of solar by now in the grid because costs were expected to be higher than for alternative sources. Even in 2010, projections were for almost no use of solar in the grid by now. By 2020, the picture had totally changed -- but even that projection was far less optimistic than the current one. The 2023 prediction shows a full-on hockey stick of the sort that makes investors salivate.

The reason? Technology has cut costs far faster than expected.

I have a personal point of reference here. I was part of a SWAT team at the Department of Energy in 2010 (led by Matt Rogers) that was investing $37.5 billion of Stimulus Act money to nurture innovation in a whole range of energy technologies, including solar, wind, batteries and electric vehicles. We took what seemed like a very aggressive view at the time about what technology could do and projected roughly a 60% decline in the cost of solar by 2020 -- while the WSJ article says costs fell fully 90% between 2009 and today.

The cost of onshore wind power has declined by two-thirds over the same period, the article says, and there's every reason to think costs will continue to decline for both it and for solar. Not only will the technology keep improving, but costs steadily fall as manufacturing scales up.

In fact, the New York Times ran a story yesterday about concerns that solar prices are falling TOO fast. The main concern addressed in the article is political: Falling prices might undercut profitability and lead to job cuts in Georgia, where production has boomed because of the clean energy push by President Biden and where any disruption might cost him in the 2024 presidential election. However the politics play out, a plunge in prices will only accelerate adoption.

Solar and wind already have reached a tipping point: The WSJ article says four-fifths of global power capacity added last year uses renewables.

There has been some concern recently about the adoption rate for electric vehicles. While Tesla has had to cut prices on its EVs to maintain momentum, Toyota, which has resisted the move to EVs, has been taking a victory lap because its sales of hybrids have soared this year. The CEO of Mazda, Masahiro Moro, told Fortune the other day that, “we have not put a goal on [the move to EVs]. We will move as fast as the customer. We never want to surprise them with new technology.”

Still, the "disappointing" numbers for EV sales showed a 51% increase for the first three quarters of this year in the U.S. And the chart from the WSJ shows that expectations for growth remain stratospheric, as charging infrastructure will be built out and "range anxiety" will diminish.

The WSJ article says total cost of ownership for small and midsized EVs has dropped below that of cars with internal combustion engines in China and Europe and may cross that dividing line in the U.S. next year. (While EVs cost more up-front, they require far less maintenance, and electricity typically costs much less per mile than gasoline.)

As with solar and wind, costs for EVs will continue to drop as production scales up, and the technology will continue to improve. In fact, battery costs are projected to reach territory by 2025 that we would have considered the Holy Grail during my stint at the Department of Energy: Goldman Sachs predicts that the average cost for an EV battery will fall below $100 per kilowatt hour. That would be down more than 93% since 2008 and a 40% decline just since 2022. Goldman Sachs projects that prices will keep falling 11% a year through 2030.

Of course, the context for all this improvement is a climate that is continuing to heat up. At this point, we're just trying to slow the rate of deterioration and minimize the increase in storms and wildfires that are devastating so many people and, in the process, generating massive insurance claims.

But we have to start somewhere.

Cheers,

Paul

P.S. As I said last week, I encourage you to attend the Town Hall being held on Thursday in Washington, DC, by my colleagues at the Insurance Information Institute. It will bring insurance executives and policy makers together to focus on how to attack the climate crisis. There are more details here, including a discount code. I hope to see you there.