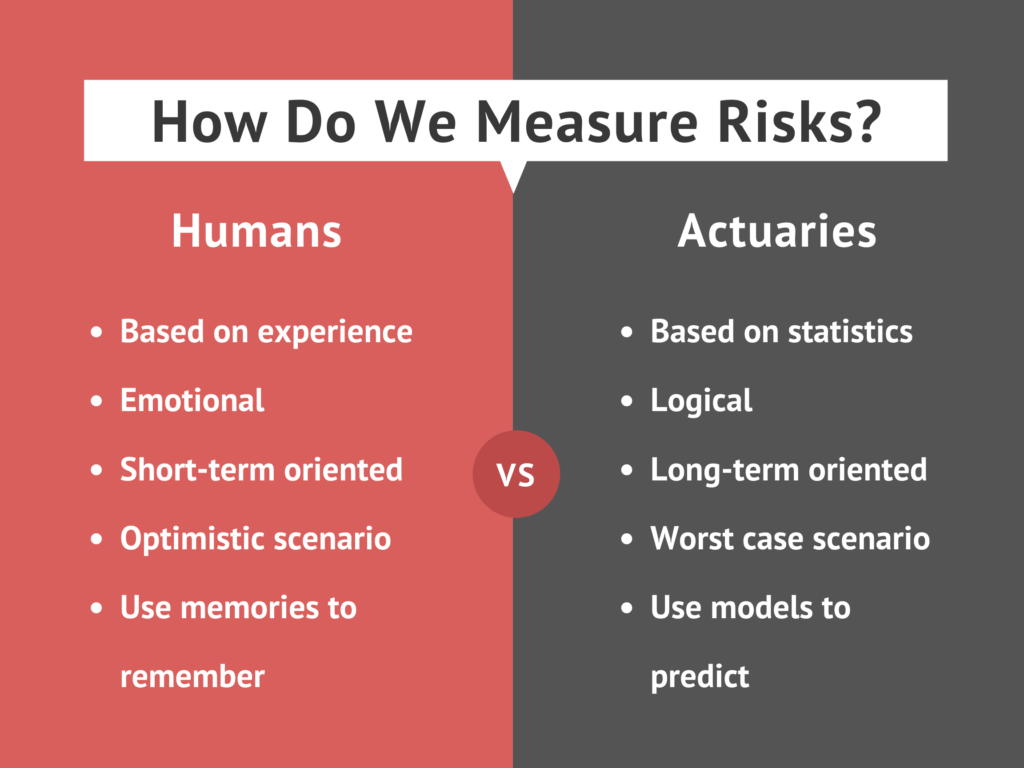

Although risk is at the center of insurance, there is a question that is not asked enough: How do we measure risks?

When you ask an actuary to measure the likelihood of occurrence for a specific risk in a year, (s)he uses models based on various data sets. However, none of us use actuarial models in our daily life to measure risk (including actuaries). We simply tap our memories about that risk. If memories are vivid, we think that risk is higher.

Using memories does not sound like the best way to measure a risk, so why are we so simple and superficial in our daily lives?

Contrary to popular belief, our brains often mislead us, and the problems also affect hard missions like measuring the probability of an event occurrence. Here are seven cognitive bias and shortcuts that lead us to make wrong decisions about risks.

1. Availability Heuristic

The stronger our memories, the stronger our emotions. While measuring the probability of a risk, we check our memories based on:

- Recent events

- Frequent events

- Tragic events

- Unexpected events

Negative events are easier to remember. It is quite possible that we exaggerate risks in such cases. For this reason, car insurance, which has high loss frequency, is one of the biggest lines.

2. Myopia

No matter how healthy our eyes are, our brains have trouble seeing the distant future. Because our most basic instant is survival, we focus too much on today and do not pay attention to risks in the future.

Even if we do not save enough today for retirement, we do not think that we will face income problems. This explains why people tend to buy mobile phones instead of life insurance.

3. Amnesia

Even as we exaggerate recent events, we forget them quickly. Insurance penetration increases rapidly after a natural disaster but declines to the previous level in few years.

After Hurricane Katrina, the number of flood insurance policies in the U.S. grew by 14%, which is three to four times the growth rates observed in previous years. Policy numbers dropped to pre-Katrina levels in just three years.

4. Overconfidence

Another bias is the tendency to exaggerate our talent and performance. Self-confidence is usually a good thing, but having too much of it can cause us to underestimate the risks.

Among car drivers in the U.S., 90% said they were better than average.

5. Illusion of Control

Thinking we have full control in our lives can make us insensitive to risks. There are people who afraid to travel by plane on one side, and people who drive motorcycles on the other…. Sometimes one person can belong to both groups.

Being injured or dying while riding a motorcycle is much more likely than an airplane crash, but we might take that risk because we have the illusion of control.

See also: COVID-19: Actuaries Now All Wrong

6. Optimism

Being optimistic about the future is one of the most beneficial features of humankind. Based on optimism, we make long-term investments, have children and go to work every day. But when it comes to risk management, being optimistic can be misleading.

People are more balanced when considering good things and bad things in their past. But while thinking about the future we generally give weight to good things. This optimism might prevent us from seeing possible risks.

7. Black Swans

All swans were thought to be white until the Australian continent was discovered. Black swans appeared on the continent, and this term is used as a metaphor for hard-to-predict, tragic and rare events: 9/11 attacks, the 2008 economic crisis and now COVID-19.

Black swans are ignored until they happen. After thatm the effects are highly exaggerated. Finally, at some point, they are ignored again. That means today's black swan COVID-19 is a great opportunity for the insurance industry, at least for the next 10 years, just as the terror insurance market was in the U.S. after the 9/11 attacks.

Behavioral Insurance

To provide an insurance service based on consumers' needs, we should stop for a bit and try to understand deeply how they measure risks. As the gap increases between insurers' and consumers' considerations about risks, it becomes much more difficult to meet their expectations.

Behavioral economic theories can help insurers in many areas, from product development to pricing, from marketing to claim managements. It is time to meet with the “behavioral insurance” approach beyond the traditional insurance practice based on statistics and calculations.