Cyber attacks were once on the periphery of American business consciousness. That mindset changed over the past two years. A series of devastating events, including the 2014 cyber attack against Sony, catapulted cyber liability concerns from an IT department issue to a major priority for boardrooms across America. As U.S. government officials concluded that North Korea was behind the attack, many C-suite executives suddenly found themselves asking questions. Is this the start of a cyber war? Could we be the next victim? If we are, how will it affect our operations and our bottom line? Do our insurance policies cover any of these costs?

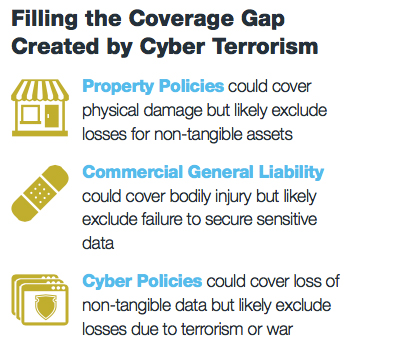

Today, many insurance buyers look to their cyber insurance policies to fill coverage gaps that often exist in other policies. For example, a property policy may respond to physical damage from a named peril, but it will likely exclude loss for non-tangible assets as a result of a cyber attack. Similarly, a commercial general liability policy will likely provide liability coverage for causing bodily injury because of negligence but exclude coverage for liability because of a failure to secure sensitive data from hackers.

Many policyholders may be unaware that some, though not all, of these cyber policies contain specific terrorism and war exclusions. As a result, gaps in cyber insurance coverage can exist in cases like the Sony breach, where government agencies, like the FBI, conclude that a foreign government or terrorist organization is responsible for the attack.

Is a Cyber Attack "Terrorism" or "War"?

Immediately following the Sony attack, President Obama referred to it by saying, "I don’t think it was an act of war . . . but cyber vandalism." Then, on April 1, 2015, President Obama signed the Executive Order on Cybersecurity with the goal of protecting the private sector against hackers and thereby bolstering national security. The order seeks to identify and punish individuals behind attacks, but it could also lead some to categorize an apparent hacking event or act of cyber terrorism as an "act of war."

Changes in government definitions trickle down into coverage disputes because many policies that exclude or include "war," "terrorism" or "cyber terrorism" either fail to define those terms or define them by referring to standard government definitions.

Government Definitions of Terrorism, Cyber Terrorism and War

THE TERRORISM RISK INSURANCE ACT (TRIA)

"Act of terrorism" is defined as any act certified by the secretary of the Treasury in concurrence with the secretary of State and the attorney general of the U.S. to be:

» an act of terrorism

» a violent act or an act that is dangerous to human life, property or infrastructure

» an act resulting in damage within the United States or Outside (on a U.S.-flagged vessel, aircraft or U.S. mission)

» an act committed by an individual or individuals acting on behalf of any foreign person or foreign interest, as part of an effort to coerce the civilian population, U.S. policy or the U.S. government.

The secretary of the Treasury may not delegate his certification authority, and his decision to certify an act or not is not subject to judicial review.

DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE (DOD)

The DOD defines "terrorism" as "the unlawful use of violence or threat of violence, often motivated by religious, political or other ideological beliefs, to instill fear and coerce governments or societies in pursuit of goals that are usually political." The term "act of war" is understood to mean "a use of force [that may] invoke a state's inherent right to lawful self-defense."

DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE (DOJ)/FEDERAL BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION (FBI)

The FBI defines "cyber terrorism" as "the premeditated, politically motivated attack against information, computer systems, computer programs and data [that] results in violence against non-combatant targets by subnational groups or clandestine agents."

DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY (DHS)

The National Infrastructure Protection Center (NIPC), (formally a branch of DHS), defines "cyber terrorism" as "a criminal act perpetrated through computers resulting in violence, death and/or destruction and creating terror for the purpose of coercing a government to change its policies."

Cyber Terrorism and the 'Act of War' Exclusion

Cyber policies are relatively new and manuscript products; as such, the wording varies significantly. Many policies contain a standard exclusion for "war, invasion, acts of foreign enemies, hostilities (whether war is declared or not), civil war, rebellion, revolution, insurrection, military or usurped power, confiscation, nationalization, requisition, or destruction of, or damage to, property by or under the order of any government, public or local authority..." An attack by the Taliban, for example, would probably fit within the exclusion as an act sponsored by a "public or local authority."

Traditionally, war exclusions were relatively narrow; they required an actual war or, at the very least, "warlike operations"; "for there to be a 'war,' a sovereign or quasi-sovereign must engage in hostilities." Pan Am. World Airways, Inc. v. Aetna Cas. & Sur. Co., 505 F.2d 989, 1005 (2d Cir. 1974) (finding that a Jordanian terrorist group that hijacked a plane was not a de facto government for the purposes of applying the war exception).

However, the events of Sept. 11, 2001, changed the way certain events and groups were perceived and classified, ultimately leading many to label the 2014 cyber attack on Sony an "act of war."

Litigation surrounding the Sept. 11 attacks led directly to an expanded view of the war exclusion. For one thing, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the attacks were an "act of war." In re Sept. 11 Litig., 931 F. Supp. 2d 496, 512 (S.D.N.Y. 2013), an owner of a building near the site of the World Trade Center attacks sought to recover cleanup and abatement expenses for removing pulverized dust that infiltrated into the owner's building after the collapse of the Twin Towers. He sued under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act [CERCLA], which allows strict liability claims in pollution cases, but the court applied CERCLA's "act of war" exception to strict liability.

In concluding that the attacks were an act of war, the court commented that "Al Qaeda's leadership declared war on the United States, and organized a sophisticated, coordinated, and well-financed set of attacks intended to bring down the leading commercial and political institutions of the United States," id. at 509, and that "as we learned in the twentieth century, and as has been true throughout history, war can take on a formal structure of armies in contrasting uniforms confronting each other on battlefields, and war can persist for years, fought by irregular, insurgent forces and capable of causing extraordinary damage," id. at 511.

This expansion of the legal definition of "act of war" to include acts by "irregular, insurgent forces and capable of causing extraordinary damage" could lead to attacks by hacktivist groups or foreign intelligence services being considered acts of war and therefore excluded from cyber policies.

Cyber Insurance and TRIA

The Terrorism Risk Insurance Act (TRIA) is a government program designed to provide a backstop for reinsurers in the event of large terrorism-related losses (more than $100 million). There is debate over whether TRIA applies to cyber policies at all. TRIA applies to commercial property and casualty insurance coverage, but some cyber policies are written as another line of coverage, such as professional liability, which is not included in TRIA.

Even assuming that TRIA would apply to cyber insurance, for TRIA coverage to be in effect, (1) there must be losses, resulting from property damage, exceeding $100 million; and (2) they must be caused by a certified terrorism event:

(1) Property Damage: For TRIA to apply, physical property damage must occur, and what constitutes "physical damage" in the context of a cyber attack remains an open question. What we do know is that TRIA will probably not cover business interruption or reductions in business income absent some physical loss or property damage. Many cyber attacks do not involve any physical damage, which would exclude TRIA coverage.

(2) A Certified Terrorism Event: For TRIA to apply to any event, the event would need to be certified as an act of terrorism. This onerous and political certification process requires the secretary of the Treasury, secretary of State and attorney general to agree that an incident was an "act of terrorism." Many political and economic issues factor into certifying a terrorism event, which can lead to counterintuitive results. For instance, as of the date of this publication, the April 2013 Boston Marathon bombing has not been certified as a terrorist act.

Conclusion

To ensure coverage for cyber terrorism and cyber warfare, buyers of cyber insurance will need to seek out a cyber risk insurance policy that explicitly includes this coverage in the broadest terms possible. As more insurance carriers enter the cyber insurance market, one must be wary that policy terms will vary from one policy form to the next, and some will have coverage terms superior to others.