"Everything you've told me is very interesting, Mr Robert. But apart from that, what are your values?"

This was the question asked by the AXA recruitment manager after letting me spout off for 20 minutes. The year was 1991, and I was 27 years old, three of which had been professional.

"What kind of question is that? He hasn't said a word the whole interview, so is he just leading me gently toward the exit, or what"

Go for introspection, then: I talk to him about ambition as an individual driving force, about the need for it to converge with a collective goal and therefore about loyalty to the team. And that's when the recruiter comes to life, gives me a boost and challenges me. After 30 minutes of this game, the interview comes to an end.

"We'll keep you posted," he said.

On my way back to the waiting room, I picked up a leaflet about AXA's values. It talked about ambition, team spirit, loyalty and realism.

I thought, "In the end, I didn't do so badly."

A few weeks later, I received a job offer from AXA and another from the No. 2 company in the French market. I remember my meeting with my potential future boss at the other company: He was negotiating my salary demands by telling me about the great rates at the company restaurant!

See also: The Broad Reality of Diversity

So it was AXA, then only the fourth-largest French insurer but with teams united by a common base:

- The tutelary figure: Claude Bébéar ("CB"), who -- with a civil engineering diploma in his pocket -- joined an obscure provincial mutual insurer in the late '50s and rose through the ranks to take over the reins some 15 years later.

- A founding myth: a seminar in the Ténéré desert in 1985, during which the directors of the mutual company decided to create the AXA Group.

- A crazy goal: in 15 years, to turn just another French insurer into a world leader.

- The grit of the challengers: at the beginning of the '90s, to accomplish in less than two years the merger of five insurance organizations with 16,000 employees, to redeploy them by distribution channel, to adopt a single brand whose name means absolutely nothing but can be pronounced in all the countries where the group will be established.

- A decentralized organization, designed for growth: only a few key functions are centralized -- equity, brand, executive management, financial reporting, IT and data infrastructure. The rest is in the hands of the business.

- The logo, in the form of the pin that we wear: It immediately identifies us when we turn up at industry professionals meetings. The "Axiens" (give or take a letter, are they aliens?) hunt in packs.

Why all this? To illustrate that a company's culture is not a collection of mantras to be displayed as posters. Or, to be more precise, while mantras and posters may have their place, they mean nothing if they are not supported by a common DNA.

It's this DNA that moves the lines, not the posters.

"Culture eats strategy for breakfast," Peter Drucker said. The success of a strategy depends on a strong and congruent culture.

It is largely because there was this bond between employees that AXA achieved its ambition.

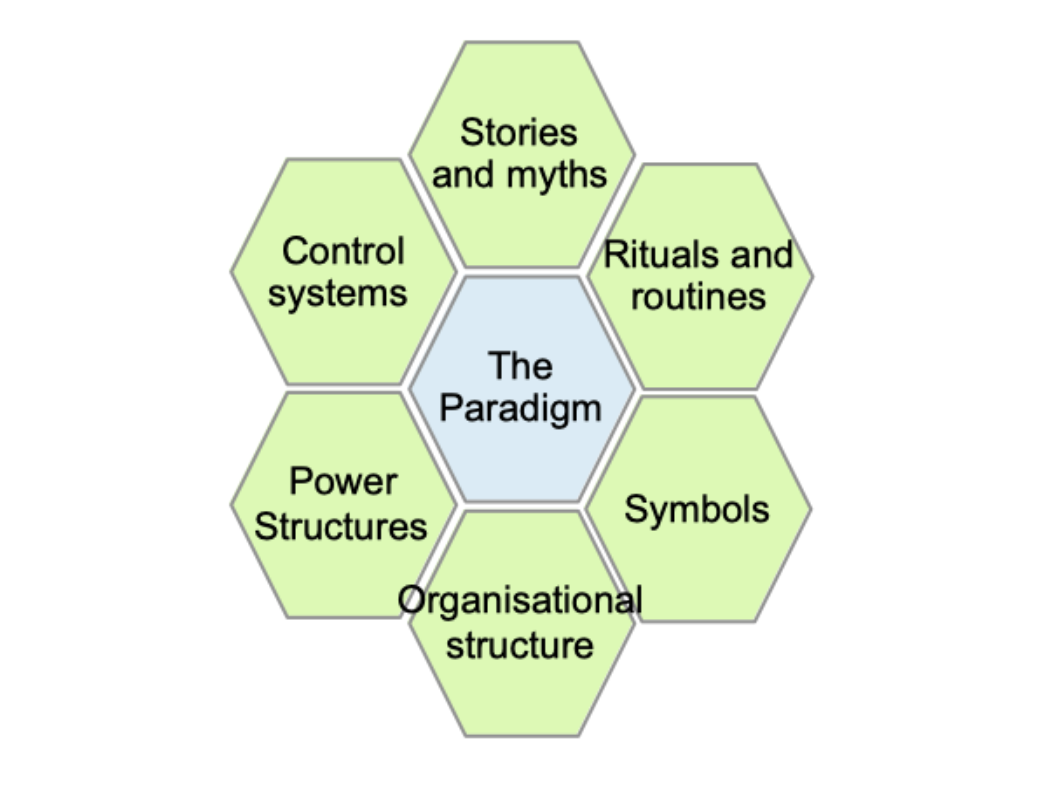

G.Johnson, R.Whittington and K.Scholes have modeled the factors that make up a company's culture, in the service of its purpose (the "paradigm"). Their representation echoes AXA's DNA, as I have just outlined it:

This diagram implies that a culture takes time to build. So how can start-ups claim to be building a solid culture from scratch?

See also: Why Innovation Fails (and How You Can Succeed)

I'm reminded of my first few weeks with Paris-based insurtech ALAN. When we hadn't yet started work on designing our first insurance product, the two founders spent a morning in one-on-one talks. Then they came to see me to submit a first version of what they presented as ALAN's values. I laughed.

"Oh, yeah? You expect to make posters out of the value, like AXA does?!"

Of course not: "We want to offer our customers simple, transparent insurance. We think we'll only be able to do that if we're really simple and transparent in the way we work." Aligning corporate values and value proposition.

For ALAN, the idea is not to focus on the slogans of simplicity and transparency for their own sake, but to apply them to day-to-day operations: decision-making on company priorities, HR policy, communication, etc.

And because ALAN is a start-up, there isn't a question of aligning existing procedures with simplicity and transparency, but of designing a simple and transparent way of working by design. As a result, atypical practices such as the absence of hierarchy, public pay scales, decision-making without meetings, etc. were deployed very early on.

In the end, these practices harmonize behavior before shaping the start-up's culture, which is probably the opposite of what would happen in an established company.

Operating methods also need to be adapted as the company grows and new issues emerge. The challenge is to flesh out the framework of practices by forging their alignment with values. This is how ALAN is now presenting a set of leadership principles, inspired by other fast-growing companies (such as Amazon). What distinguishes these leadership principles from values is that they are more operational than incantatory.

One of the keys to developing a strong culture therefore lies in the adoption of consistent behavior within teams, much more than in posters displayed in meeting rooms.

The question then is how to spread these behaviors throughout the company? This is where the practices of ALAN and AXA can come together.

ALAN breaks down its leadership principles into behavioral traits, which are m easured during the recruitment and individual assessment processes. Clearly, an applicant who does not demonstrate strong alignment (or an employee who deviates from the norm) does not have much of a future at ALAN.

What remains to be managed is the risk of producing an army of clones from recruiting profiles that are too similar. For me, this is a general issue for start-ups, which goes beyond the introduction of behavioral criteria into HR policy.

AXA deployed an original process in the '90s, consisting of training its managers in Model Netics, which illustrate 150 management situations. This approach provides managers with common responses, even though they do not necessarily have an academic background in management literature. It is also a common language, in the primary sense of the term, marking those who use it with the stamp of those in the know. Example: "So, how are you going to get your team on board with this project? It's simple, I've got my recipe: 50% Attitude-stair-steps and 50% Planning-path."

In this case, the focus is on practices rather than behavior, so there is a good fit with the diversity of profiles that make up a mature organization. The question of sustainability may arise (once you've trained the management, what do you do?); in fact, AXA has gradually abandoned this tool.

Which goes to show that you can have a strong culture in a young organization: Culture emerges from shared behaviors that form the backbone that allows the organization to grow.

Which goes to show that, for a mature organization, culture is the bedrock of individual commitment in the service of collective ambition. Otherwise, there's always the "mantras and posters" option!