Apparently, the wellness industry does not have a monopoly on invalid research.

A study came out in

The Lancet–the British equivalent of the

New England Journal of Medicine — finding that the only safe level of alcohol consumption was: none. As the principal investigator said: “Alcohol poses dire ramifications for future population health in the absence of policy action today.” This finding generated myriad headlines like

this one at CNBC:

Or NPR:

Or NPR:

And how often do those

two outlets agree with Fox News?

One thing you learn if you hang around wellness promoters long enough is that oftentimes a close perusal of the study in question shows the opposite of what the authors intended. Or, as we often say: “In wellness, you don’t have to challenge the data to invalidate it. You merely have to read the data. It will invalidate itself.” And the same is true here.

For example, Denmark leads the world in the number of drinkers — and has life expectancy higher than about 90% of the world’s countries. The lowest alcohol consumers? Pakistan — which ranks #130 in life expectancy. You might say: “Wait, aren’t there many other factors involved in life expectancy?” And the answer is, of course there are. None of those were controlled for in any way in this meta-analysis. To begin with, the more people drink, the more other unhealthy habits they are likely to have.

But that’s not the crux of what is wrong with this study. Two other things should lead wellness professionals to the opposite conclusion: that light drinking is perfectly OK. The remainder of this post addresses those.

Absolute risk vs. relative risk

Absolute vs. relative risk is one of our (many) pet peeves. Here are two other examples that we have had to smack down:

- The American Cancer Society warns of a 22% increase in colon cancer among people under 50, but it turns out that absolute rate of colon cancer in younger people is so low that the chances of your life being saved by screening at age 45 are about the same as your chances of being struck by lightning. The media had a field day with that one, too.

- Before that, speaking of colons, a study came out showing that red meat increased risk of dying from colon cancer. Once again, it turned out — using the data right in the study — that more people are killed by lightning than by colon cancer due to eating more red meat than average. Yet, once again, the media had a field day.

From the media’s perspective, this makes sense. After all, who is going to click through on a headline that says: “Low-quality study finds trivial relationship between variables”?

See also: 2 Studies of Why Wellness Fails

In the case of this alcohol study, looking behind the headlines proved equally insightful. (And thank you to Aaron Carroll of The

New York Times‘ Upshot for suggesting it.)

Here is the lead-in:

Alcohol is a leading risk factor for death and disease worldwide, and is associated with nearly one in 10 deaths in people aged 15-49 years old, according to a Global Burden of Disease study published in The Lancet that estimates levels of alcohol use and health effects in 195 countries between 1990 and 2016.

Based on their analysis, the authors suggest that there is no safe level of alcohol as any health benefits of alcohol are outweighed by its adverse effects on other aspects of health, particularly cancers.

Read the first paragraph again. Two observations:

- Almost no one dies between the ages of 15 and 49, so being responsible for “nearly” 10% of those deaths means that alcohol kills about 0.001% of people in that age bracket every year.

- The authors have conflated two things: alcohol and excess alcohol. Virtually all of those deaths in that age bracket were due to the latter, a fact that the authors conveniently overlooked when demonizing any level. of consumption.

Reading a bit further in…

They estimate that, for one year, in people aged 15-95 years, drinking one alcoholic drink a day [1] increases the risk of developing one of the 23 alcohol-related health problems [2] by 0.5%, compared with not drinking at all (from 914 people in 100,000 for one year for non-drinkers aged 15-95 years, to 918 in 100,000 people a year for 15-95 year olds who consume one alcoholic drink a day)

Hello? A 0.5% increase in relative risk? And the increase in absolute risk (not calculated) is four per 100,000 people a year — or 0.004% a year. Even two drinks a day increases absolute risk only by 0.06% a year. (Once you get beyond two drinks a day, the chance of harm accelerates exponentially…but that’s not news.)

What the he** are employees going to consume instead?

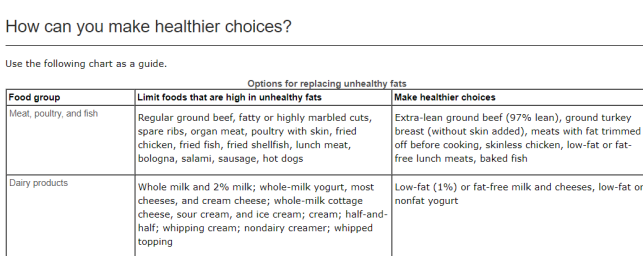

Our biggest beef with this study is the same as with just about every wellness program: Everything is off-limits. Even foods that are OK in moderation for most people — like

full-fat dairy,

salt, oils,

cholesterol/eggs and red meat — are singled out for criticism by health risk assessments. And now alcohol.

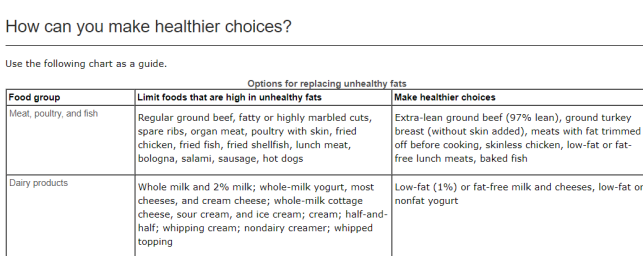

Unfortunately, the more foods you demonize, the less likely it is that any employee will pay any attention to any of your dietary pronouncements. And to the extent they do. well, what are they going to eat instead? Here is Cerner telling people that non-fat yogurt is a “healthier choice.” Trivia question: What added ingredient makes nonfat yogurt taste good?

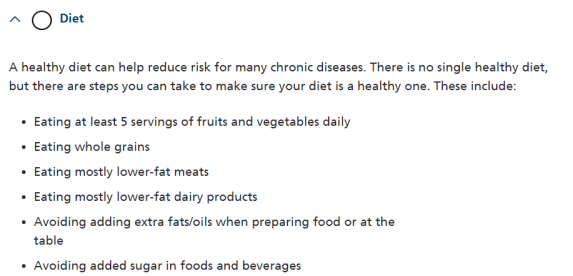

Here is Optum railing against oils:

And Cerner, once again, this time incriminating dietary cholesterol, which of course has no impact on blood cholesterol for most people:

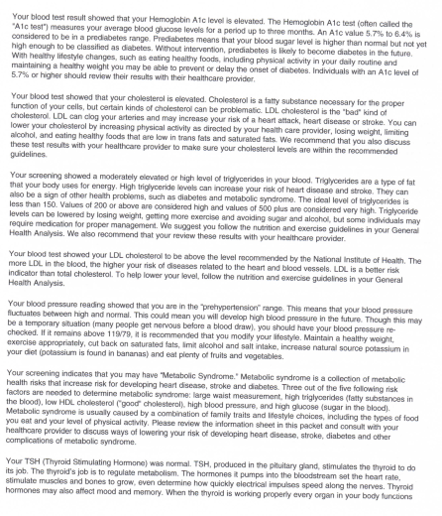

Finally, here is Interactive Health hyperventilating about something-or-other in its HRA feedback to an employee. We don’t know what it is other than, given the provenance, it’s wrong. Fortunately, no employee is going to plow through this anyway.

Conclusion

Conclusion

Treat this alcohol finding the same way you would treat advice from most health risk assessments: ignore it.

Or NPR:

Or NPR:

And how often do those two outlets agree with Fox News?

And how often do those two outlets agree with Fox News?

One thing you learn if you hang around wellness promoters long enough is that oftentimes a close perusal of the study in question shows the opposite of what the authors intended. Or, as we often say: “In wellness, you don’t have to challenge the data to invalidate it. You merely have to read the data. It will invalidate itself.” And the same is true here.

For example, Denmark leads the world in the number of drinkers — and has life expectancy higher than about 90% of the world’s countries. The lowest alcohol consumers? Pakistan — which ranks #130 in life expectancy. You might say: “Wait, aren’t there many other factors involved in life expectancy?” And the answer is, of course there are. None of those were controlled for in any way in this meta-analysis. To begin with, the more people drink, the more other unhealthy habits they are likely to have.

But that’s not the crux of what is wrong with this study. Two other things should lead wellness professionals to the opposite conclusion: that light drinking is perfectly OK. The remainder of this post addresses those.

Absolute risk vs. relative risk

Absolute vs. relative risk is one of our (many) pet peeves. Here are two other examples that we have had to smack down:

One thing you learn if you hang around wellness promoters long enough is that oftentimes a close perusal of the study in question shows the opposite of what the authors intended. Or, as we often say: “In wellness, you don’t have to challenge the data to invalidate it. You merely have to read the data. It will invalidate itself.” And the same is true here.

For example, Denmark leads the world in the number of drinkers — and has life expectancy higher than about 90% of the world’s countries. The lowest alcohol consumers? Pakistan — which ranks #130 in life expectancy. You might say: “Wait, aren’t there many other factors involved in life expectancy?” And the answer is, of course there are. None of those were controlled for in any way in this meta-analysis. To begin with, the more people drink, the more other unhealthy habits they are likely to have.

But that’s not the crux of what is wrong with this study. Two other things should lead wellness professionals to the opposite conclusion: that light drinking is perfectly OK. The remainder of this post addresses those.

Absolute risk vs. relative risk

Absolute vs. relative risk is one of our (many) pet peeves. Here are two other examples that we have had to smack down:

Here is Optum railing against oils:

Here is Optum railing against oils:

And Cerner, once again, this time incriminating dietary cholesterol, which of course has no impact on blood cholesterol for most people:

And Cerner, once again, this time incriminating dietary cholesterol, which of course has no impact on blood cholesterol for most people:

Finally, here is Interactive Health hyperventilating about something-or-other in its HRA feedback to an employee. We don’t know what it is other than, given the provenance, it’s wrong. Fortunately, no employee is going to plow through this anyway.

Finally, here is Interactive Health hyperventilating about something-or-other in its HRA feedback to an employee. We don’t know what it is other than, given the provenance, it’s wrong. Fortunately, no employee is going to plow through this anyway.

Conclusion

Treat this alcohol finding the same way you would treat advice from most health risk assessments: ignore it.

Conclusion

Treat this alcohol finding the same way you would treat advice from most health risk assessments: ignore it.