Increasingly, we live in a world of now. Instantaneous access to digital real-time data and news has simply become a given. You may be surprised to know that the Federal Reserve has taken notice.

To this point, GDP data from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) has arrived after the fact. From the perspective of a financial market and investors that are always looking ahead, GDP data is “yesterday’s news.” Moreover, revisions to GDP can come to us months or even years later, essentially becoming an afterthought for decision making.

Recently, though, the Atlanta Federal Reserve has developed what it terms a GDPNow model. It essentially mimics the methodology used by the BEA to estimate inflation-adjusted, or real, growth in the U.S. economy. The GDPNow forecast is constructed by aggregating statistical model forecasts of the 13 components that compose the BEA’s GDP calculation.

Private forecasters of GDP, such as the Blue Chip Consensus, use similar approaches. Their forecasts are usually updated monthly or quarterly, but many are not publicly available, and many do not specifically forecast the components of GDP. The Atlanta Fed GDPNow model circumvents these shortcomings, forming a relatively precise estimate of what the BEA will announce for the previous quarter’s GDP. The model is still young, but it is beginning to be discovered more widely among the analytical community.

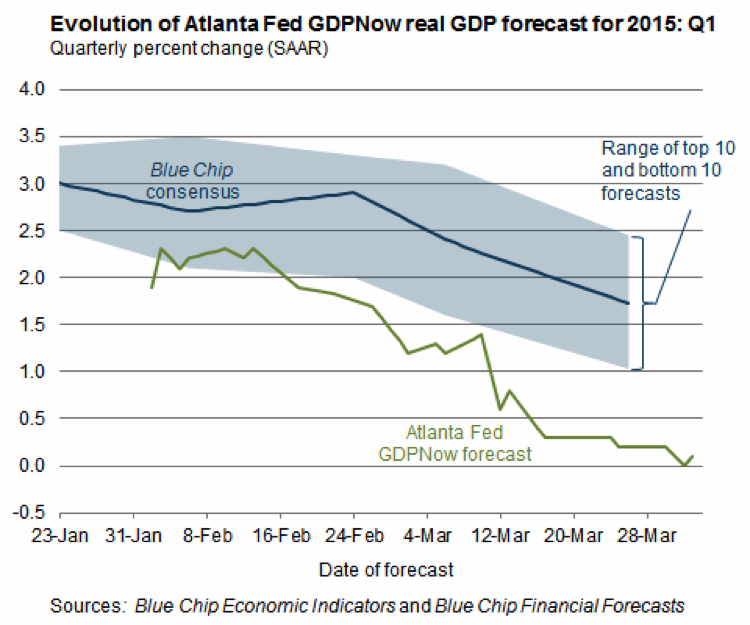

The reason we highlight this new tool is that we’ve incorporated it into our continuing, top-down review of the U.S. economy. More important to our “here and now” thinking is the current reading of this new model. As you can see in the next chart, the forecast by the Atlanta Fed for Q1 2015 U.S. real GDP growth is 0.1%, up from 0% at the end of March. As is also clear from the chart, as of the end of the March, Blue Chip economists were collectively predicting 1.7% growth -- quite a difference.

Chart Source: Atlanta Federal Reserve

Why the drop in the Atlanta Fed real-time forecast for Q1 2015 real GDP? As we look at the underlying numbers in the model, we see recent weakness in personal consumption. Many had predicted an increase in consumption with lower gasoline prices, but that has not played out, at least not yet. Weakness in residential and non-residential construction has also played a part in the downward revision. Weather on the East Coast has not been kind to builders as of late, but that’s a seasonal issue easily overcome by sunshine. Importantly, slowing in U.S. exports and equipment orders meaningfully influenced the March drop in the Atlanta Fed model.

We know global currencies have been weak; the highlight over the last six months has been the euro. With a lower euro, European exports have actually picked up as of late, and the message is clear: The strong dollar is beginning to hurt U.S. exports. We do not see this changing soon. (As you know, the importance of relative global currency movements has been a highlight of our discussions over the past half year.) Finally, durable goods orders (orders for business equipment) have been soft as of late because of slowing in the domestic energy industry. Again, that is a trend that is not about to change in the quarters ahead given dampened global energy prices.

Like any model, the Atlanta Fed GDPNow model is an estimate. Whether Q1 U.S. real GDP comes in near zero growth remains to be seen, but the message is clear, there is downward pressure on U.S. economic growth. This pressure is set against a backdrop of already documented slowing in the non-U.S. global economy. Perhaps most germane to what lies ahead for investors in 2015 is what the U.S. Fed will do in terms of raising interest rates -- or not, if indeed the slowing that the Atlanta Fed model predicts materializes.

We believe this slowing will become a real dilemma for the Fed this year and a potential issue for investors. The Fed has been backed into quite the proverbial corner. Whether the U.S. economy is slowing, the Fed is going to need to start raising interest rates for one very important reason.

It just so happens that the end of the second quarter of 2015 will mark an anniversary of sorts. It will be six years since the current economic expansion in the U.S. began. As of July, ours will be tied for the fourth-longest U.S. economic expansion on record (since the Fed began keeping official track in 1945). There have been 11 economic expansions over this period, so this is no minor feat.

The second quarter of this year will also mark the 6 1/2-year point for the U.S. economy operating under the Federal Reserve’s zero interest rate policy. You’ll remember that, during the darker days of late 2008 and early 2009, the Fed introduced 0% interest rates as an emergency monetary measure. That was deemed acceptable as crisis policy. Given that the FED has maintained that policy, it is essentially saying that the current economic cycle has not only been one of the lengthiest on record, but simultaneously is the longest U.S. economic crisis on record.

As we look ahead, the “crisis” in the eyes of the Fed will come to an end as it contemplates higher short-term interest rates.

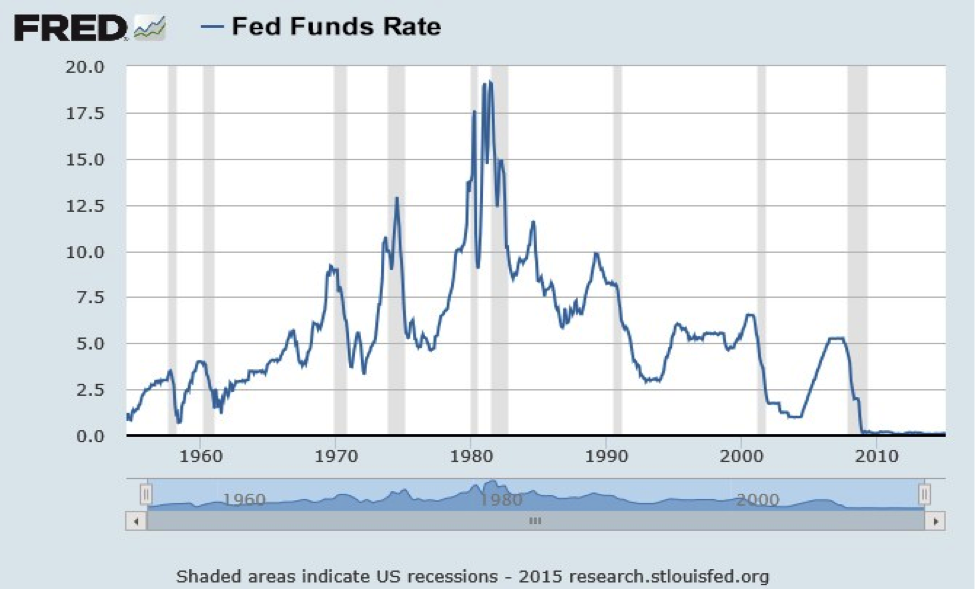

Although it still remains to be seen what the Fed will decide and when, there is one very important consideration that must be entering their interest-rate-policy decision making at this point in the economic cycle -- a consideration they will never speak of publicly. Let’s start with a look at the history of the federal funds rate (the shortest maturity interest rate the Fed directly controls). Alongside the historical rhythm of the funds rate are official U.S. recession periods in the shaded blue bars.

Chart Source: St. Louis Federal Reserve

There is one striking and completely consistent behavior: The Fed has lowered the federal funds rate in every recession since at least 1954. There are no exceptions. You can see the punchline coming, can’t you? Just how does one lower interest rates from zero to stimulate a potential slowdown in the economy?

Of course, in the European banking system and in the European bond market (government and corporate paper), we are witnessing negative yields. Capital is essentially so concerned over principal safety, it is willing to pay to be invested in a perceived safe balance sheet. Will we witness the same phenomenon in the U.S.? A move to negative interest rates in the U.S. would further punish pension funds, which are not only starved for return but are still underfunded despite fantastic returns for financial assets over the past five years -- and Baby Boomers have been rapidly moving into their retirement/pension collection years.

Without venturing into negative-interest-rate territory, the Fed is essentially out of interest rate bullets in its monetary policy arsenal. It’s out of the very ammunition it has employed in each and every recession of the prior six decades. If the U.S. were to enter a recession, the Fed would be unable to act on the interest-rate front, as it has for generations.

Is the U.S. teetering on recession? Not as far as we can see, despite the Atlanta Fed GDPNow model's reading of very close to 0% growth. We need to remember that U.S. GDP growth has been below average in the current cycle and that the cycle is not young. But the time to contemplate questions such as we are posing is well before a recessionary event. If the Fed is going to raise interest rates, it should be while the economy is still growing. Although the Fed will never speak of this publicly, it cannot be trapped at the zero bound (0% interest rates) when the next U.S. recession ultimately arrives.

The proverbial clock of history is ticking just a bit louder as we enter the second quarter of 2015. Is this, perhaps, the key reason the Fed will need to at least begin raising interest rates this year regardless of the near-term tone to the economy?

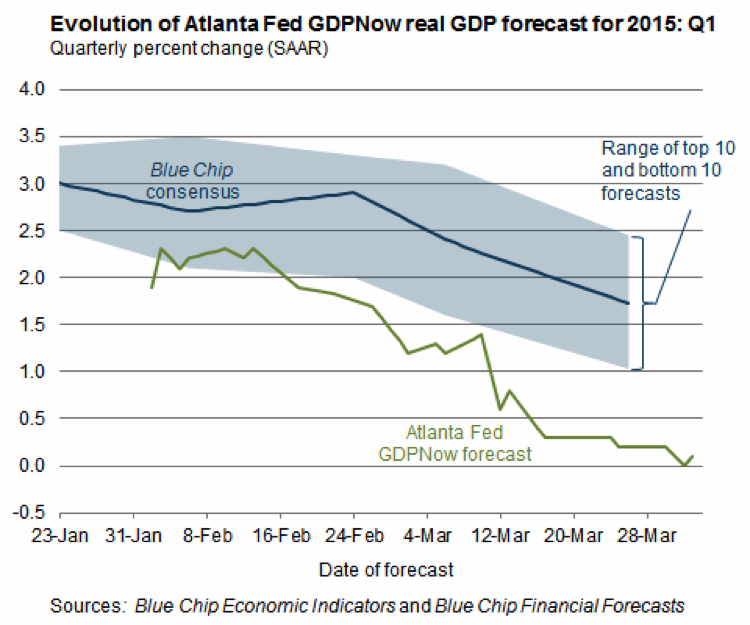

Chart Source: Atlanta Federal Reserve

Why the drop in the Atlanta Fed real-time forecast for Q1 2015 real GDP? As we look at the underlying numbers in the model, we see recent weakness in personal consumption. Many had predicted an increase in consumption with lower gasoline prices, but that has not played out, at least not yet. Weakness in residential and non-residential construction has also played a part in the downward revision. Weather on the East Coast has not been kind to builders as of late, but that’s a seasonal issue easily overcome by sunshine. Importantly, slowing in U.S. exports and equipment orders meaningfully influenced the March drop in the Atlanta Fed model.

We know global currencies have been weak; the highlight over the last six months has been the euro. With a lower euro, European exports have actually picked up as of late, and the message is clear: The strong dollar is beginning to hurt U.S. exports. We do not see this changing soon. (As you know, the importance of relative global currency movements has been a highlight of our discussions over the past half year.) Finally, durable goods orders (orders for business equipment) have been soft as of late because of slowing in the domestic energy industry. Again, that is a trend that is not about to change in the quarters ahead given dampened global energy prices.

Like any model, the Atlanta Fed GDPNow model is an estimate. Whether Q1 U.S. real GDP comes in near zero growth remains to be seen, but the message is clear, there is downward pressure on U.S. economic growth. This pressure is set against a backdrop of already documented slowing in the non-U.S. global economy. Perhaps most germane to what lies ahead for investors in 2015 is what the U.S. Fed will do in terms of raising interest rates -- or not, if indeed the slowing that the Atlanta Fed model predicts materializes.

We believe this slowing will become a real dilemma for the Fed this year and a potential issue for investors. The Fed has been backed into quite the proverbial corner. Whether the U.S. economy is slowing, the Fed is going to need to start raising interest rates for one very important reason.

It just so happens that the end of the second quarter of 2015 will mark an anniversary of sorts. It will be six years since the current economic expansion in the U.S. began. As of July, ours will be tied for the fourth-longest U.S. economic expansion on record (since the Fed began keeping official track in 1945). There have been 11 economic expansions over this period, so this is no minor feat.

The second quarter of this year will also mark the 6 1/2-year point for the U.S. economy operating under the Federal Reserve’s zero interest rate policy. You’ll remember that, during the darker days of late 2008 and early 2009, the Fed introduced 0% interest rates as an emergency monetary measure. That was deemed acceptable as crisis policy. Given that the FED has maintained that policy, it is essentially saying that the current economic cycle has not only been one of the lengthiest on record, but simultaneously is the longest U.S. economic crisis on record.

As we look ahead, the “crisis” in the eyes of the Fed will come to an end as it contemplates higher short-term interest rates.

Although it still remains to be seen what the Fed will decide and when, there is one very important consideration that must be entering their interest-rate-policy decision making at this point in the economic cycle -- a consideration they will never speak of publicly. Let’s start with a look at the history of the federal funds rate (the shortest maturity interest rate the Fed directly controls). Alongside the historical rhythm of the funds rate are official U.S. recession periods in the shaded blue bars.

Chart Source: Atlanta Federal Reserve

Why the drop in the Atlanta Fed real-time forecast for Q1 2015 real GDP? As we look at the underlying numbers in the model, we see recent weakness in personal consumption. Many had predicted an increase in consumption with lower gasoline prices, but that has not played out, at least not yet. Weakness in residential and non-residential construction has also played a part in the downward revision. Weather on the East Coast has not been kind to builders as of late, but that’s a seasonal issue easily overcome by sunshine. Importantly, slowing in U.S. exports and equipment orders meaningfully influenced the March drop in the Atlanta Fed model.

We know global currencies have been weak; the highlight over the last six months has been the euro. With a lower euro, European exports have actually picked up as of late, and the message is clear: The strong dollar is beginning to hurt U.S. exports. We do not see this changing soon. (As you know, the importance of relative global currency movements has been a highlight of our discussions over the past half year.) Finally, durable goods orders (orders for business equipment) have been soft as of late because of slowing in the domestic energy industry. Again, that is a trend that is not about to change in the quarters ahead given dampened global energy prices.

Like any model, the Atlanta Fed GDPNow model is an estimate. Whether Q1 U.S. real GDP comes in near zero growth remains to be seen, but the message is clear, there is downward pressure on U.S. economic growth. This pressure is set against a backdrop of already documented slowing in the non-U.S. global economy. Perhaps most germane to what lies ahead for investors in 2015 is what the U.S. Fed will do in terms of raising interest rates -- or not, if indeed the slowing that the Atlanta Fed model predicts materializes.

We believe this slowing will become a real dilemma for the Fed this year and a potential issue for investors. The Fed has been backed into quite the proverbial corner. Whether the U.S. economy is slowing, the Fed is going to need to start raising interest rates for one very important reason.

It just so happens that the end of the second quarter of 2015 will mark an anniversary of sorts. It will be six years since the current economic expansion in the U.S. began. As of July, ours will be tied for the fourth-longest U.S. economic expansion on record (since the Fed began keeping official track in 1945). There have been 11 economic expansions over this period, so this is no minor feat.

The second quarter of this year will also mark the 6 1/2-year point for the U.S. economy operating under the Federal Reserve’s zero interest rate policy. You’ll remember that, during the darker days of late 2008 and early 2009, the Fed introduced 0% interest rates as an emergency monetary measure. That was deemed acceptable as crisis policy. Given that the FED has maintained that policy, it is essentially saying that the current economic cycle has not only been one of the lengthiest on record, but simultaneously is the longest U.S. economic crisis on record.

As we look ahead, the “crisis” in the eyes of the Fed will come to an end as it contemplates higher short-term interest rates.

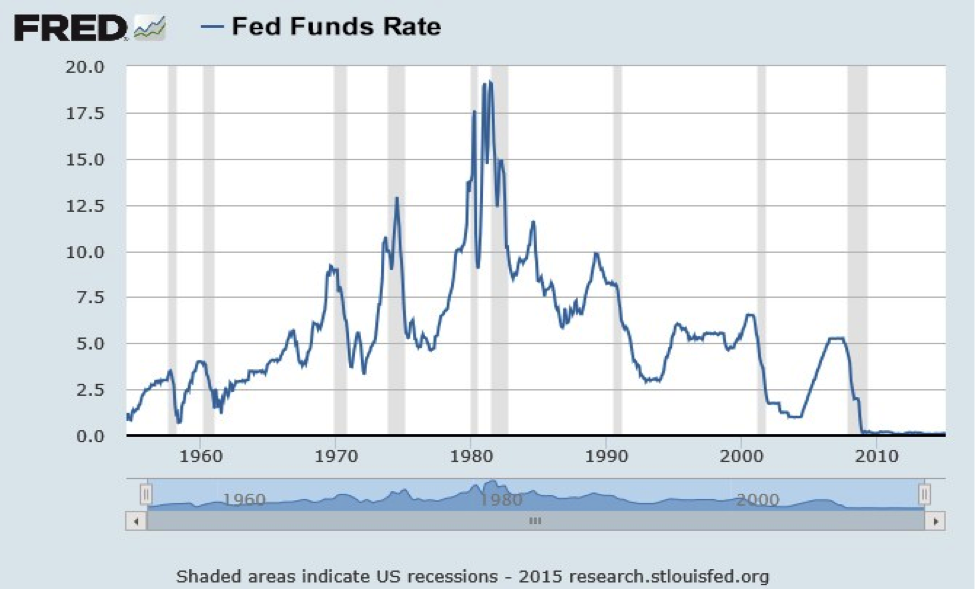

Although it still remains to be seen what the Fed will decide and when, there is one very important consideration that must be entering their interest-rate-policy decision making at this point in the economic cycle -- a consideration they will never speak of publicly. Let’s start with a look at the history of the federal funds rate (the shortest maturity interest rate the Fed directly controls). Alongside the historical rhythm of the funds rate are official U.S. recession periods in the shaded blue bars.

Chart Source: St. Louis Federal Reserve

There is one striking and completely consistent behavior: The Fed has lowered the federal funds rate in every recession since at least 1954. There are no exceptions. You can see the punchline coming, can’t you? Just how does one lower interest rates from zero to stimulate a potential slowdown in the economy?

Of course, in the European banking system and in the European bond market (government and corporate paper), we are witnessing negative yields. Capital is essentially so concerned over principal safety, it is willing to pay to be invested in a perceived safe balance sheet. Will we witness the same phenomenon in the U.S.? A move to negative interest rates in the U.S. would further punish pension funds, which are not only starved for return but are still underfunded despite fantastic returns for financial assets over the past five years -- and Baby Boomers have been rapidly moving into their retirement/pension collection years.

Without venturing into negative-interest-rate territory, the Fed is essentially out of interest rate bullets in its monetary policy arsenal. It’s out of the very ammunition it has employed in each and every recession of the prior six decades. If the U.S. were to enter a recession, the Fed would be unable to act on the interest-rate front, as it has for generations.

Is the U.S. teetering on recession? Not as far as we can see, despite the Atlanta Fed GDPNow model's reading of very close to 0% growth. We need to remember that U.S. GDP growth has been below average in the current cycle and that the cycle is not young. But the time to contemplate questions such as we are posing is well before a recessionary event. If the Fed is going to raise interest rates, it should be while the economy is still growing. Although the Fed will never speak of this publicly, it cannot be trapped at the zero bound (0% interest rates) when the next U.S. recession ultimately arrives.

The proverbial clock of history is ticking just a bit louder as we enter the second quarter of 2015. Is this, perhaps, the key reason the Fed will need to at least begin raising interest rates this year regardless of the near-term tone to the economy?

Chart Source: St. Louis Federal Reserve

There is one striking and completely consistent behavior: The Fed has lowered the federal funds rate in every recession since at least 1954. There are no exceptions. You can see the punchline coming, can’t you? Just how does one lower interest rates from zero to stimulate a potential slowdown in the economy?

Of course, in the European banking system and in the European bond market (government and corporate paper), we are witnessing negative yields. Capital is essentially so concerned over principal safety, it is willing to pay to be invested in a perceived safe balance sheet. Will we witness the same phenomenon in the U.S.? A move to negative interest rates in the U.S. would further punish pension funds, which are not only starved for return but are still underfunded despite fantastic returns for financial assets over the past five years -- and Baby Boomers have been rapidly moving into their retirement/pension collection years.

Without venturing into negative-interest-rate territory, the Fed is essentially out of interest rate bullets in its monetary policy arsenal. It’s out of the very ammunition it has employed in each and every recession of the prior six decades. If the U.S. were to enter a recession, the Fed would be unable to act on the interest-rate front, as it has for generations.

Is the U.S. teetering on recession? Not as far as we can see, despite the Atlanta Fed GDPNow model's reading of very close to 0% growth. We need to remember that U.S. GDP growth has been below average in the current cycle and that the cycle is not young. But the time to contemplate questions such as we are posing is well before a recessionary event. If the Fed is going to raise interest rates, it should be while the economy is still growing. Although the Fed will never speak of this publicly, it cannot be trapped at the zero bound (0% interest rates) when the next U.S. recession ultimately arrives.

The proverbial clock of history is ticking just a bit louder as we enter the second quarter of 2015. Is this, perhaps, the key reason the Fed will need to at least begin raising interest rates this year regardless of the near-term tone to the economy?