Violent crime, a major and growing problem in this country, is exacerbated by the fact that many crimes go unreported. But there’s a simple fix to the lack of reporting: Make it easier for people to tip off authorities anonymously.

Developments in communications technology and in social media can play a decisive role in increasing reporting, especially among young people. Once authorities have more information, they can not only track down more criminals but can develop a fuller picture of where and under what conditions violent crimes occur, and can develop better prevention programs.

In California, the Visalia campus of the College of the Sequoias has a program allowing individuals to report suspicious behavior on campus to local police anonymously via text, voice mail or email.

“Our best resource, by far, is the students and faculty right here on campus,” Chief of the Police department Bob Masterson told the student newspaper . “Even if you’re not the victim, you could be a great witness.”

Many students said the program, TipNow, keeps them safer; they also consider it a good idea for all campuses.

Such programs are essential because violent crime remains an unfortunate truth in the U.S. According to the FBI's national crime statistics, 1.2 million violent crimes were committed in the U.S. in 2012, and even seemingly safe, self-contained campus environments like schools, colleges, hotels, hospitals and corporations are not immune.

At U.S. hospitals, the violent crime rate per 100 hospital beds rose 25%, from 2.0 incidents in 2012 to 2.5 incidents last year, according to research released by the IHSS Foundation at the International Association for Healthcare Security and Safety (IAHSS). The rate of disorderly conduct incidents experienced the biggest jump, from 28 per 100 hospital beds in 2012 to 39.2 last year (a rise of 40%). A separate IHSS Foundation study found that 89% of the hospitals surveyed had at least one event of workplace violence in the previous 12 months.

The federal Bureau of Justice Statistics’ National Crime Victimization Survey reported the following statistics for workplace violence between 1993 and 1999:

- While working or on duty, U.S. residents experienced 1.7 million violent victimizations annually, including 1.3 million simple assaults, 325,000 aggravated assaults, 36,500 rapes and sexual assaults, 70,000 robberies and 900 homicides.

- Workplace violence accounted for 18% of all violent crime.

From 1997 through 2009, 335 murders occurred on college campuses, according to data from the U.S. Department of Education (2010). Three-fifths of campus attacks in a 108-year span occurred in the past two decades.

Yet many crimes go unreported to campus authorities. A 1997 study about campus violence by Sloan, Fisher and Cullen found that only 35% of violent crimes on college campuses were reported to authorities.

There are various reasons for not reporting crimes. For example, many may regard a crime as too minor a matter to report or may consider it a private matter. Many studies have shown a reluctance to report crimes or other suspicious activities out of fear of the authorities or of criminal retribution.

For instance, in February 2009 in San Gabriel, Calif., two gunmen opened fire inside a coffee shop, killing one and wounding six others, but police had trouble finding witnesses to what appeared to be a gang-related attack even though the shop was crowded with at least 40 people. Sheriff's spokesman Steve Whitmore was quoted as saying, "We know people saw something, and we need them to come forward and help us solve this crime."

Too many Americans are inculcated with the belief that "the authorities will attend to it" – without considering that, in many cases, the appropriate law enforcement agency is unaware of a danger. Although many domestic terrorist events and campus shootings are committed by those whose previous actions were seen by those around them as odd, or even threatening, too often these observations go unreported.

This is why the concept of anonymous reporting is important: to get more information from the campus community. This anonymity is now possible.

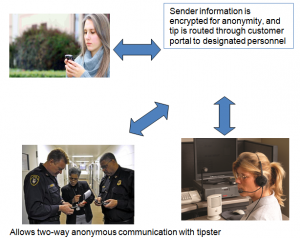

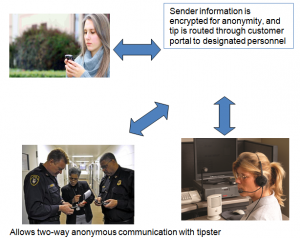

TipNow receives tips via SMS/text, email, voice and mobile-app. When the tips hit the TipNow server, the sender’s information is encrypted. The tip is then disseminated to a pre-defined set of administrators on the system via email and SMS/text. The administrators can ask for more information from the tipster, still anonymously. For extra security, the server will delete all identifying information in 24 to 72 hours.

The system looks like this:

In a recent interview, an anti-terrorism official (name withheld at his request) expressed his view on prevention: "The ability to gather information, sift through it to find what is useful intelligence – and then rapidly get that information to the right people – can and has made the difference between tragedy and that tragedy being averted.”

In a recent interview, an anti-terrorism official (name withheld at his request) expressed his view on prevention: "The ability to gather information, sift through it to find what is useful intelligence – and then rapidly get that information to the right people – can and has made the difference between tragedy and that tragedy being averted.”

In a recent interview, an anti-terrorism official (name withheld at his request) expressed his view on prevention: "The ability to gather information, sift through it to find what is useful intelligence – and then rapidly get that information to the right people – can and has made the difference between tragedy and that tragedy being averted.”