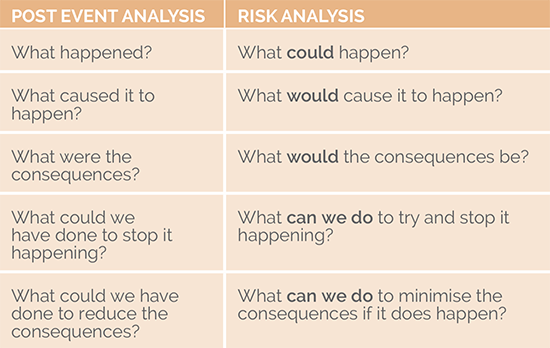

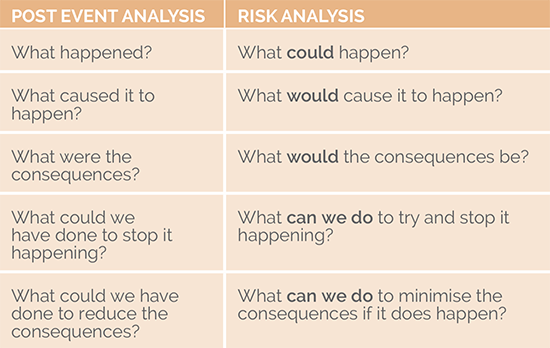

To that end, risk analysis can be viewed as post-event analysis before the event's occurring.

The rule of thumb I use is that if the risk in your register could not have a post-event analysis conducted on it if it happened – then it is not a risk!

If you apply this approach to your list of risks events, you will:

• Reduce the number of risks in your risk register considerably; and (more importantly)

• Make it a lot easier to manage those risks.

Try it with your risk register and see what results you get.

A Risk Is a Risk

Commonly, people talk of different types of risk: strategic risk, operational risk, security risk, safety risk, project risk, etc. Segregating these risks and managing them separately can actually diminish your risk-management efforts.

What you need to understand about risk and risk management is that a risk is a risk is a risk -- the only thing that differs is the context within which you manage that risk.

All risks are events, and each has a range of consequences that need to be identified and analyzed to gain a full understanding. For example;

You have a group identifying hazard risks, isolated from the risk-management team (a common occurrence), and they tend to look at possible consequences in one dimension only – the harm that may be caused. Decisions on how to handle the risk will be made based on this assessment. What hasn’t been done, however, is to assess the consequence against all of the organizational impact areas that you find in your consequence matrix. As a result, the assessment of that risk may not be correct; for instance, there may be significant consequences in terms of compliance that don't show up as an issue in terms of safety.

If you only look at risk in one dimension, you may make a decision that creates a downstream risk that is worse than the event you're trying to prevent. For instance, you may mitigate a safety-related risk but create an even greater security risk.

The moral of the story: Managing risk in silos will diminish risk management within your organization.

In about 80% of cases, you can’t do anything about the consequences of the event; what you are trying to do is stop the event from happening in the first place.

To that end, risk analysis can be viewed as post-event analysis before the event's occurring.

The rule of thumb I use is that if the risk in your register could not have a post-event analysis conducted on it if it happened – then it is not a risk!

If you apply this approach to your list of risks events, you will:

• Reduce the number of risks in your risk register considerably; and (more importantly)

• Make it a lot easier to manage those risks.

Try it with your risk register and see what results you get.

A Risk Is a Risk

Commonly, people talk of different types of risk: strategic risk, operational risk, security risk, safety risk, project risk, etc. Segregating these risks and managing them separately can actually diminish your risk-management efforts.

What you need to understand about risk and risk management is that a risk is a risk is a risk -- the only thing that differs is the context within which you manage that risk.

All risks are events, and each has a range of consequences that need to be identified and analyzed to gain a full understanding. For example;

You have a group identifying hazard risks, isolated from the risk-management team (a common occurrence), and they tend to look at possible consequences in one dimension only – the harm that may be caused. Decisions on how to handle the risk will be made based on this assessment. What hasn’t been done, however, is to assess the consequence against all of the organizational impact areas that you find in your consequence matrix. As a result, the assessment of that risk may not be correct; for instance, there may be significant consequences in terms of compliance that don't show up as an issue in terms of safety.

If you only look at risk in one dimension, you may make a decision that creates a downstream risk that is worse than the event you're trying to prevent. For instance, you may mitigate a safety-related risk but create an even greater security risk.

The moral of the story: Managing risk in silos will diminish risk management within your organization.

In about 80% of cases, you can’t do anything about the consequences of the event; what you are trying to do is stop the event from happening in the first place.The Right Way to Enumerate Risks

Managers often think about risks too broadly, when they need to focus on specific events they hope to prevent.

To that end, risk analysis can be viewed as post-event analysis before the event's occurring.

The rule of thumb I use is that if the risk in your register could not have a post-event analysis conducted on it if it happened – then it is not a risk!

If you apply this approach to your list of risks events, you will:

• Reduce the number of risks in your risk register considerably; and (more importantly)

• Make it a lot easier to manage those risks.

Try it with your risk register and see what results you get.

A Risk Is a Risk

Commonly, people talk of different types of risk: strategic risk, operational risk, security risk, safety risk, project risk, etc. Segregating these risks and managing them separately can actually diminish your risk-management efforts.

What you need to understand about risk and risk management is that a risk is a risk is a risk -- the only thing that differs is the context within which you manage that risk.

All risks are events, and each has a range of consequences that need to be identified and analyzed to gain a full understanding. For example;

You have a group identifying hazard risks, isolated from the risk-management team (a common occurrence), and they tend to look at possible consequences in one dimension only – the harm that may be caused. Decisions on how to handle the risk will be made based on this assessment. What hasn’t been done, however, is to assess the consequence against all of the organizational impact areas that you find in your consequence matrix. As a result, the assessment of that risk may not be correct; for instance, there may be significant consequences in terms of compliance that don't show up as an issue in terms of safety.

If you only look at risk in one dimension, you may make a decision that creates a downstream risk that is worse than the event you're trying to prevent. For instance, you may mitigate a safety-related risk but create an even greater security risk.

The moral of the story: Managing risk in silos will diminish risk management within your organization.

In about 80% of cases, you can’t do anything about the consequences of the event; what you are trying to do is stop the event from happening in the first place.

To that end, risk analysis can be viewed as post-event analysis before the event's occurring.

The rule of thumb I use is that if the risk in your register could not have a post-event analysis conducted on it if it happened – then it is not a risk!

If you apply this approach to your list of risks events, you will:

• Reduce the number of risks in your risk register considerably; and (more importantly)

• Make it a lot easier to manage those risks.

Try it with your risk register and see what results you get.

A Risk Is a Risk

Commonly, people talk of different types of risk: strategic risk, operational risk, security risk, safety risk, project risk, etc. Segregating these risks and managing them separately can actually diminish your risk-management efforts.

What you need to understand about risk and risk management is that a risk is a risk is a risk -- the only thing that differs is the context within which you manage that risk.

All risks are events, and each has a range of consequences that need to be identified and analyzed to gain a full understanding. For example;

You have a group identifying hazard risks, isolated from the risk-management team (a common occurrence), and they tend to look at possible consequences in one dimension only – the harm that may be caused. Decisions on how to handle the risk will be made based on this assessment. What hasn’t been done, however, is to assess the consequence against all of the organizational impact areas that you find in your consequence matrix. As a result, the assessment of that risk may not be correct; for instance, there may be significant consequences in terms of compliance that don't show up as an issue in terms of safety.

If you only look at risk in one dimension, you may make a decision that creates a downstream risk that is worse than the event you're trying to prevent. For instance, you may mitigate a safety-related risk but create an even greater security risk.

The moral of the story: Managing risk in silos will diminish risk management within your organization.

In about 80% of cases, you can’t do anything about the consequences of the event; what you are trying to do is stop the event from happening in the first place.