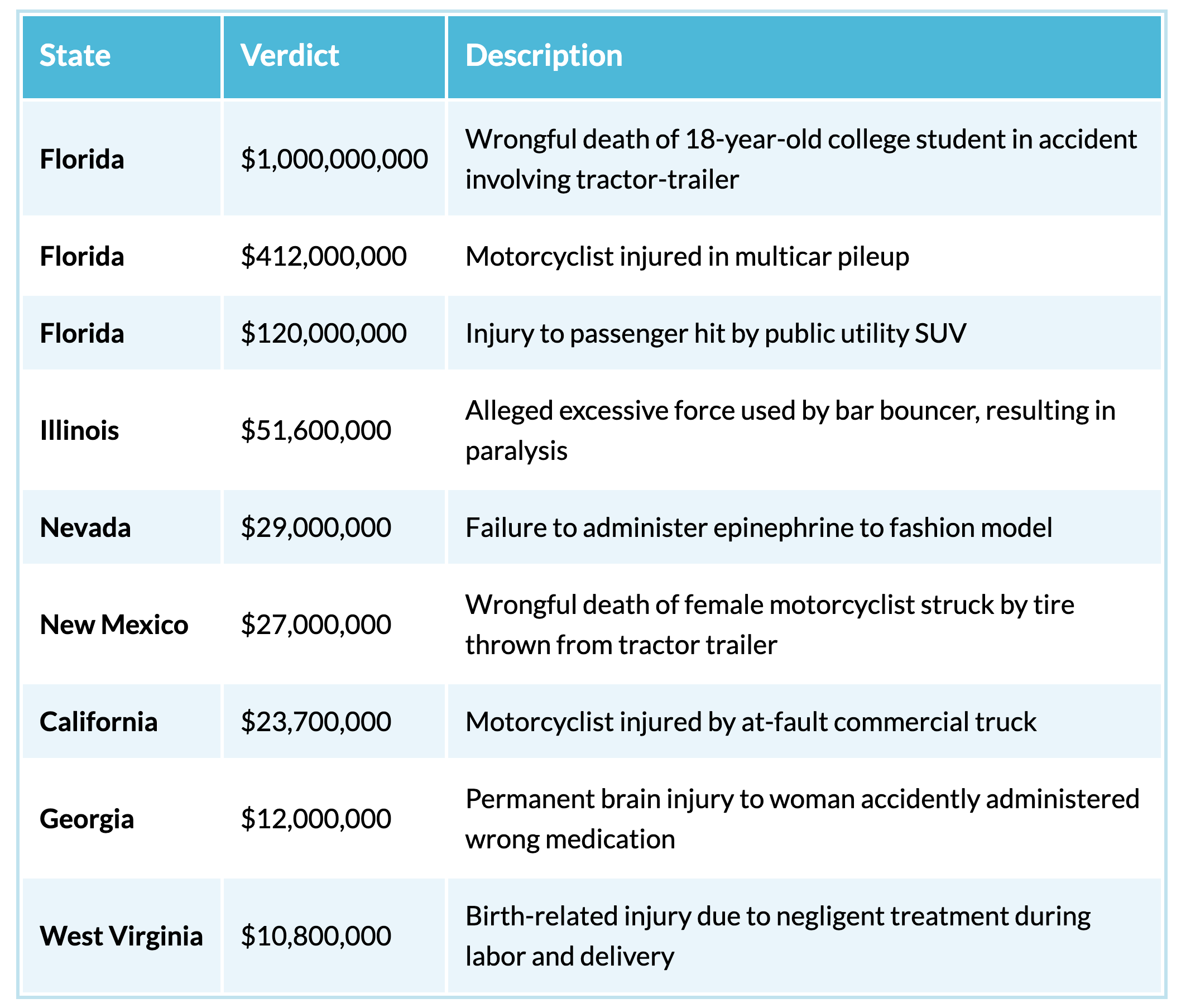

As society continues its halting emergence from the COVID‑19 pandemic, court activity has resumed. With that activity has come a return to the eyebrow-raising verdicts seen pre‑pandemic:

Source: Law 360

Fueling those verdicts are the trends discussed previously in this blog series – changing juror demographics and attitudes, a plaintiffs bar eager to feed juror concerns over personal safety and perceived disenfranchisement, as well as litigation funders seeking to maximize returns in the current low-interest environment.

With preliminary signs indicating that social inflation will continue its seemingly inexorable rise, an obvious question comes to mind: At what point does social inflation severely constrict the availability of certain lines of coverage and thereby give rise to legal remedies, such as tort reform? Are we approaching a precipice?

Past as Prologue

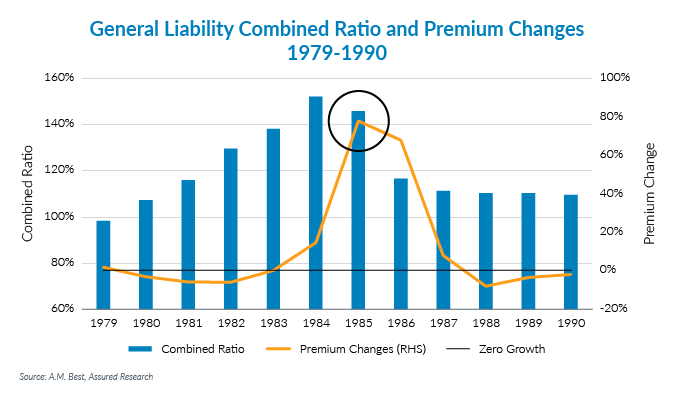

A look backward reveals a time when social inflation ran rampant and caused much consternation among policyholders and carriers alike:

During this period, the liability combined ratio peaked at 151% in 1984. Liability premiums skyrocketed as well, increasing 78% in 1985 and 68% in 1986. Not surprisingly, coverage for certain lines vanished, with specialty lines – such as Medical Malpractice – being particularly hard-hit. Seeking to quell this maelstrom, state legislatures ushered in an unprecedented era of tort reform that resulted in 39 states passing 82 different tort reform measures between 1985 and 1990. The era also spawned creation of well-known advocacy groups, such as the American Tort Reform Association.

By placing caps on noneconomic damages, reducing statutes of limitation and implementing other procedural changes, tort reform stabilized and ultimately reduced liability premiums. However, its full effect proved to be only temporary, as evidenced by a number of successful legal challenges on equal protection and other grounds. Many of the late-20th century tort reform measures remain intact but continue to be under attack.

See also: The Future Isn’t What It Used to Be

Back to the Future?

While social inflation shows signs of someday igniting into a full-blown conflagration, the indications are mixed as to whether that will occur sooner or later. While there are many metrics to consider, industry combined ratios for 2020 remain below 100; moreover, the top eight writers of Personal Auto saw their combined ratio drop to 88 in 2020 from 93 in 2019.

While pandemic-driven lockdowns and working from home likely caused the decline in 2020, the fact remains that combined ratios will need to climb stratospherically before a reprise of the crisis last seen in the 1980s occurs, although even incremental growth has ramifications.

Nevertheless, the social inflation fires could be either fanned or extinguished, at least partially, by a number of cultural factors:

- Individual Perceptions of Risk Tolerance – During this COVID‑19 pandemic, each of us is making personal decisions as to how much – or how little – risk we are willing to tolerate. Do we return to the office? How comfortable are we eating in restaurants? To what degree is out-of-state travel – and by what means – acceptable?

How an individual answers these questions will provide insight as to attitudes toward personal responsibility, risk tolerance and expectations of a corporation or business defending itself in a tort liability lawsuit. - Intergenerational Wealth Disparity/Economic Inequality – Much has been written about increased wealth concentration, the decline of the traditional middle class and the growing number of dislocated workers subsisting on gig or part-time jobs. Similarly, multiple data points suggest that Baby Boomers hold a disproportionately large percentage of the country’s wealth.

Will these economic trends continue to fuel the distrust and resentment that is thought to partially explain the spate of “nuclear” verdicts and out-sized settlements? Or will the promise of an estimated $3 trillion wealth transfer from the Baby Boom generation and hoped-for economic improvement post-COVID bear out and level the economic disparity, and could it restore the societal faith in institutions that once existed? - Impact of Social Media – Twitter, Facebook and LinkedIn are only a few of the tech companies that have enabled people to connect in ways unimaginable a generation ago. However, to varying degrees these platforms have also become fruitful ground for the spread of misinformation – and in some instances outright disinformation campaigns. One commentator suggests conditions are ripe for groups to display what social scientists refer to as “in‑grouping;” that is, a belief that social identity is a source of strength and superiority and that other groups are to be blamed for their problems.

Could this spread of misinformation be influencing juror attitudes and perceptions of certain groups? Do we now have a growing number of Americans living in an alternate reality that does not comport with credible and factual information? Or is the effect too slight to be much of a factor at all? - Insurance Industry Response – As with other industries, insurance will continue to experience significant transition. Over time, the industry’s 2.8 million employees have moved from being managed by Baby Boomers and Gen Xers to Millennials. Filling entry-level underwriting positions are recent Generation Z graduates, with many coming from the growing number of strong risk management and insurance programs that have arisen in the last two decades.

At one level, this transition will entail loss of decades of practical experience. At another, it will represent the career dawn of a workforce more educated and more culturally diverse than its predecessors. Presumably, with their greater educational and cultural diversity will come creative and “out of the box” solutions to vexing industry problems, such as social inflation. As mentioned elsewhere in this series, “big data,” artificial intelligence and predictive modeling hold the key.

Conclusion

Over the past several years social inflation has caused much discussion – and the initiation of exhaustive searches for its causes and potential solutions. This 5‑part blog series has endeavored to contribute to that effort, with perspectives offered from a variety of disciplines. While the journey will continue for many more months and possibly years, with the ultimate solution far from known, the insurance industry has shown itself capable of meeting great challenges, such as the one social inflation represents.

How quickly and effectively the industry meets that challenge rests on the shoulders of the dedicated professionals who have made insurance their chosen career.