Policymakers in many states increasingly enact medical fee schedules in the quest to limit the growth of hospital costs. They often seek a reference point or benchmark to which they can tie reimbursement rates. Usually, that benchmark is either Medicare rates in the state or some measure of historic charges by the hospitals. Medicare rates are usually seen by healthcare providers as unreasonably low; charge-based fee schedules are often seen by payers as unnecessarily high.

This study examines an alternative benchmark for workers’ compensation fee schedules—prices paid by group health insurers. In concept, this benchmark has certain advantages. Unlike Medicare, the group health rates are not the result of political decisions driven by the exigencies of the federal budget. Rather, these rates are the result of negotiations between the payers and the providers. Unlike a charge-based benchmark, group health rates are what is actually paid to providers. This is important given the growing public attention to the arbitrariness of many hospital charges.

The major limitation of using group health prices paid as a benchmark for workers’ compensation fee schedules is that these prices are seen by group health insurers as proprietary. However, one state, Montana, has adopted a fee schedule based on group health prices paid and implemented relatively straightforward processes to balance the need for a fee schedule and the need to protect the proprietary information of the group health insurers.

This article does the following: (1) describes the major findings of the study, (2) suggests a framework for thinking about whether prices paid by workers’ compensation payers are too high or too low, and (3) discusses the Montana approach.

Major FindingsWhat do we find when we compare the prices paid to hospital outpatient departments by group health and workers’ compensation payers? Among the major findings of this study are:

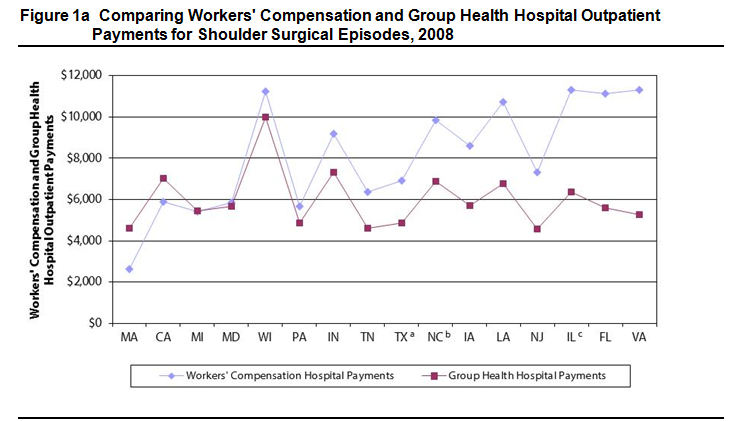

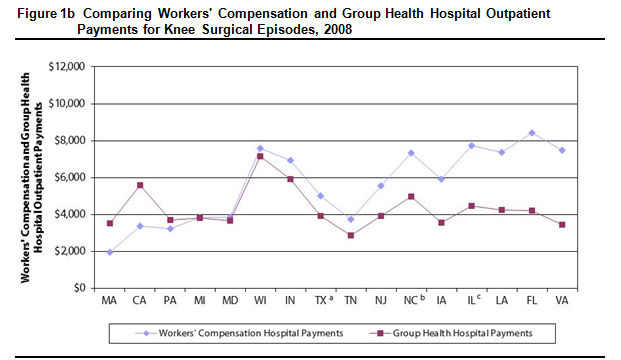

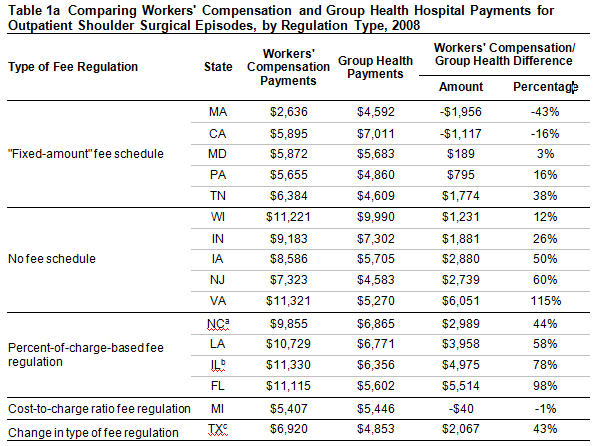

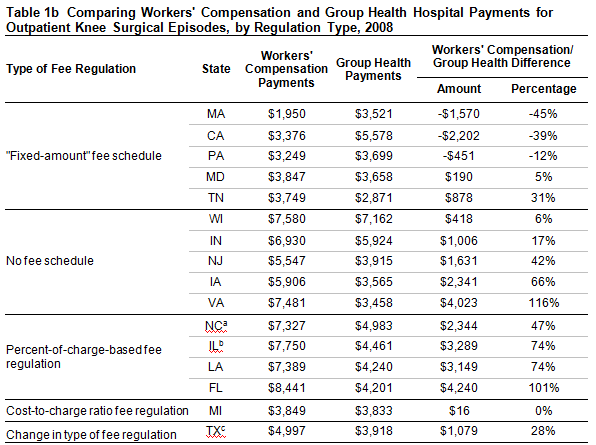

- In many study states, workers’ compensation hospital outpatient payments for common surgical episodes were higher, and often much higher, than those paid by group health. For example, in half of the study states, workers’ compensation paid at least $2,000 (43%) more for a common shoulder surgery (see Figures 1a and 1b).

- The amount by which workers’ compensation payments exceeded group health payments (“the workers’ compensation premium”) was highest in the study states with either no fee schedule or a charge-based fee schedule (Tables 1a and 1b).

Are Prices Paid By Workers’ Compensation Payers Too Low or Too High?

Are Prices Paid By Workers’ Compensation Payers Too Low or Too High?

The comparison of workers’ compensation and group health hospital outpatient payments raises the question in many states as to whether workers’ compensation hospital outpatient rates are higher than necessary to ensure injured workers access to good quality care. For example, in Indiana, hospital outpatient services associated with shoulder surgery were, on average, reimbursed $9,183 by workers’ compensation as compared with $7,302 by group health. Is this differential of $1,881 necessary to induce hospital outpatient departments to provide facilities, supplies and staff to treat injured workers in an appropriate and timely manner?

Consider the following framework for analyzing the question. If hospital outpatient departments were willing to provide timely and good-quality care to group health patients at the prices paid by group health insurers, then two questions should be answered by policymakers:

- What is the rationale for requiring workers’ compensation payers to pay more to hospital outpatient departments than group health insurers pay for the same treatments?

- If there is such rationale for higher payment, is a large price differential necessary to get hospital outpatient departments to treat injured workers?

In addressing the first question, let’s say that the hospital outpatient department provided identical treatment for a group health patient and a workers’ compensation patient. If the care was identical—same facilities, supplies and staff—and workers’ compensation imposed no unique added costs on the hospital outpatient department, then there is little rationale for workers’ compensation payers to pay more than the group health payers.

Healthcare providers often cite a special “hassle factor” in workers’ compensation that does not exist in treating or billing for the group health patient. Common examples of the alleged hassle factor include longer payment delays, higher nonpayment rates (where the compensability was contested or where care given was not deemed appropriate), more paperwork, more missed appointments, lower patient compliance with provider instructions and so on. If these hassles are unique to workers’ compensation patients, then this forms a potential rationale for workers’ compensation paying higher prices than group health, for the same care. Let’s assume that this accurately describes the real world.

Then the question becomes: Are the unique costs imposed on hospital outpatient departments large enough to justify workers’ compensation payers having to pay $2,000-$4,000 more per surgical episode than group health payers pay for the same care? If the costs of these hassles total less than, say, $2,000, then workers’ compensation fee schedules could be lowered without adverse effects on access to care for injured workers. In other words, the large price differentials observed in this study can only be justified by the large costs of these hassles that are unique to workers’ compensation.

In applying this framework to different types of providers, where these hassles exist, some types will be larger for some kinds of providers than for others. For example, the first doctor who treats may be more exposed to nonpayment risk than other providers who treat later in the claim; or the hospital outpatient departments’ use of the operating and recovery rooms would be less affected by paperwork but exposed to payment delays. Because the majority of payments to hospital outpatient departments are for physical facilities (e.g., recovery room), equipment (e.g., the MRI machine but not the radiologists’ professional services) and supplies (e.g., crutches), it is more likely that hospital outpatient departments are more exposed to billing delays, nonpayment risk (at emergency rooms for initial care) or canceled appointments and less exposed to time-consuming paperwork hassles or patient compliance issues.

Moreover, if the additional burden that the workers’ compensation system places on hospital providers (e.g., additional paperwork, delays and uncertainty in reimbursements, formal adjudication and special focus on timely return to work) is sizable, policymakers have two choices. The first is to adopt a higher-than-typical fee schedule that embraces large costs for the hassle factor. The alternative is to identify and remediate the causes of the larger-than-typical hassles -- especially where these are rooted in statutory or regulatory requirements.

The Montana ApproachThe major limitation of group health as a benchmark for workers’ compensation is that the group health rates are the proprietary competitive information of commercial insurers. The Montana legislature found a way to use group health prices as a benchmark for its workers’ compensation fee schedule while respecting the confidentiality of the commercial insurers’ price information. The approach used is to obtain the price information (conversion factor) from each of the five largest commercial insurers and group health third-party administrators (TPAs) in the state and compute an average. The average masks the prices paid by any individual commercial insurer or TPA. In addition, the statute guarantees the confidentiality of the individual insurers’ information.

ConclusionThis study raises a number of concerns about whether fee schedules are too high or too low. There are two key pieces of information needed to address this -- (1) how much other payers in the state are paying, and (2) whether there is a unique workers’ compensation hassle factor.

This study addresses the first question for common surgeries done at hospital outpatient departments. A related WCRI study does the same for professional fees paid to surgeons and primary-care physicians.

Quantifying the presence and magnitude of any unique workers’ compensation hassle factor remains to be done. However, in some states, these studies show that workers’ compensation prices were below those paid by group health. For those states, policymakers may want to inquire about access-to-care concerns, especially for primary care. For other states, the workers’ compensation prices paid were so much higher than prices paid by group health insurers that policymakers should ask if the large differences are really necessary to ensure quality care to injured workers.

One way of framing that question using the results of the WCRI studies is as follows: “Workers’ compensation pays $10,000 to hospital outpatient departments for a shoulder surgery on an injured worker, and group health pays $6,000 for the same services. Does it make sense that if workers’ compensation paid $9,000 that hospital outpatient departments would no longer treat injured workers—preferring to treat group health patients at $6,000, or Medicare patients at a fraction of the group health price, or Medicaid patients at prices lower than Medicare?”