The three P&C venture-backed U.S. insurtech start-ups -- Lemonade, Metromile and Root -- finished 2018 with pretty good results. Quarterly growth was the slowest ever, but all three paid out in claims less than they collected in premium. All three start-up carriers have more work to do to achieve sustainable financials.

A year ago, when I started with

my friend Adrian a public conversation about insurtech statutory results, the picture was ugly -- loss ratios well over 100%, an aggressive focus on price and promotional messages on company blogs that dismissed traditional measures of success in insurance.

Since the first post titled "

5 Dispatches From Insurtech Island,” the conversation has shifted dramatically. Fast forward a year, and one founder

said he “messed up an entire quarter” because premium growth turned negative, when in fact the company generated its best quarterly loss ratio ever. In the months since, several start-ups have hired top underwriting talent from their traditional competitors, showing that they increasingly recognize the value of traditional insurance skills.

Skeptics point out that a quarter doesn’t mean much, that there’s a long way to go before reaching sustainability and that each additional point of loss gets harder to take out. True, but the increased focus this year on reducing losses and increasing prices is making a difference.

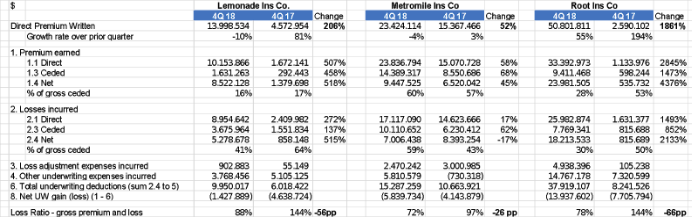

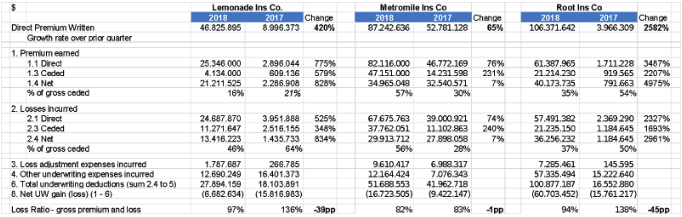

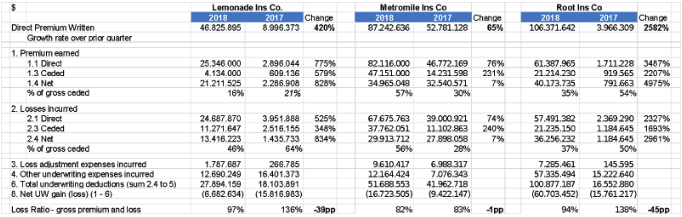

Here are the quarterly results:

I think – as already mentioned in the previous articles - these companies have strong management teams who could ultimately create valuable businesses. This will take several years, but all three companies are well-funded, even if the combination of statutory capital injections and operating losses consumes tens of millions in capital each year. (The Uber/Lyft model of growing rapidly while also incurring large losses is doubly penalized in insurance because carriers have to maintain statutory capital that increases with premium.)

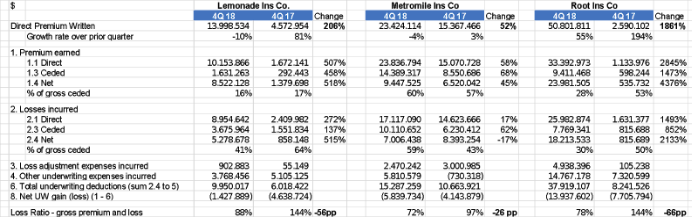

Here is a year-over-year comparison.

The three companies have sold in the last 12 months between $40 million and $110 million, less than some of the early 2017

enthusiastic forecasts that Lemonade (for example) would hit $90 million of premiums by the end of 2017. In auto, I pointed out at my

IoT Insurance Observatory plenary sessions that the pay-as-you-drive telematics approach seems to attract only the niche of customers that rarely use cars – maybe a growing niche, but not a billion-dollar business (in premium at least).

See also: 9 Pitfalls to Avoid in Setting 2019 KPIs

Loss Ratios

Loss ratios have all been below 100%, which is a great improvement from the 2017 performances. The quarterly dynamics show a positive trend, but these loss ratio levels are far from the U.S. market average for home insurance (Lemonade) and auto insurance (Root and Metromile).

While loss ratio is a fundamental insurance number – claims divided by premiums -- I've been asked how to normalize/adjust the loss ratio of a fast-growing insurtech company.

Imagine a fast-growing insurer with the following annual figures:

- Premiums written: $10 million

- Premiums earned: $6 million

- Claims paid: $2 million

- Losses incurred but unpaid: $5 million

Any of the following numbers might be called a “loss ratio”:

- Claims paid divided by premiums written: 20%

- Claims paid divided by premiums earned: 33%

- Claims paid and losses incurred divided by premiums written: 70%

- Claims paid and losses incurred divided by premiums earned: 117%

The least attractive is the right one.

Claims paid and losses incurred divided by premiums earned is the loss ratio, for a fast-growing start-up as for a large incumbent.

The others are only “exotic loss ratios.”

I’ve heard people say that accounting rules cause the loss ratio to be overstated based on the following unlucky scenario:

There is a book of business done by a one-year homeowner’s policy sold for $730. This policy will earn $2 of premium each day. If a $100 claim (net of the deductible) is received on that first day, the loss ratio is 5,000%. That’s how it works, but is it overstated? Well, as long as premium is being earned, more claims could arrive and the loss ratio could go even higher still.

Obviously, you expect the following 364 days to be less unlucky for this portfolio. But I don’t think there is any need to adjust that loss ratio…only to know that is not (statistically) relevant.

The analyzed start-ups have portfolios of more than 100,000 policies, so the bad luck can’t be accountable for eventual unfavorable loss ratios.

It could be that some approaches are specially targeted for fraud, and it only takes a few fraudsters to cause big problems in the loss ratio on a small book, as the above illustration shows. Some start-ups have advertised how quickly they pay claims, sometimes not even having a human review them, which invites unsavory people to pay a small amount to start a policy then “lose” a valuable item. Early on, when less premium has been earned, this fraud has a particularly great impact on the loss ratio. Over time, in a bigger and more balanced book, fraud gets tempered by the law of large numbers.

Additionally, some start-ups have offered large new-business discounts. If they can retain customers, reducing the premium leakage, their second-year loss ratios should be more reasonable, but the overall loss ratio will be elevated for however long they are acquiring customers with aggressive discounts.

Expense Ratios

I would love to discuss also the other lines of the income statements, but unfortunately they are not meaningful or comparable any more, because companies now move expenses among their entities not represented in the yellow books. The cost amounts represented in the yellow books are only a part of the real costs necessary to run the insurance business.

The statutory information I’m commenting on is reported only for insurance companies, not agencies, brokers or service companies. The term “insurance company” or “insurer” has a very

specific meaning: “the person who undertakes to indemnify another by insurance.” Within an insurance holding company, it is typical to have an insurer and an affiliated agency, and sometimes other affiliates such as claims administrator. The insurer pays the agency to produce policies. This may feel like moving money from one pocket to another, but there would be reasons for it -- which I won’t get into now.

The point for commentators and investors is to beware of this: If an insurer (for whom the public receives financial data) pays an affiliate 25% of its premiums to provide certain services, then the insurer’s expenses (which are reported in the yellow book) are set at (or close to) 25% of their premiums, regardless of what they actually are.

Major investors are typically privy to large amounts of information and can disentangle the back-and-forth between the insurer, agency and holding company. For smaller investors, or those who simply pick up a statutory filing, it is easy to be misled.

At the beginning of 2018, Lemonade was no longer consolidating its parent and affiliate expenses into Lemonade Insurance Co., its statutory entity. Lemonade’s CEO commented that this change was at the request of its home state regulator. Root followed suit in October 2018, so the 4Q18 expense ratio is moved to 28% from the 70% in the 3Q18. So the “new” expense ratios (and therefore combined ratios) are artificial and not comparable with the previous ones or with competitors'.

While regulators may have reasons for their actions, it is better for students of insurance innovation to know the full, real financials, so as to determine if the start-ups are ever able to “walk the talk” of better expense efficiency from “being built on a digital substrate.” Unfortunately, bloggers are not the main audience of statutory filings. Nonetheless, innovation cheerleaders, investors and journalists …please pay attention to these accounting differences before commenting the performances.

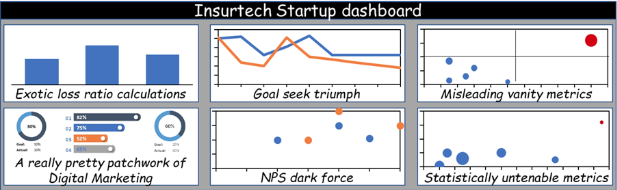

Since the beginning of the quarterly discussion of U.S.-based insurtech carriers’ financials based on their public filings, many have responded that these players needed to be evaluated on other metrics, too. I agree, so let’s look at one of those measures and talk about some questions to determine whether the measure really stacks up.

Misleading vanity metrics

The insurance value chain is complex and difficult to compare across models. This can lead to comparisons between very different companies. Take these two hypothetical companies:

- Company A — flashy Start-up Insurance Co. uses outsourced call centers, bots, incessant Instagram ads, comparison rater websites, third-party claims administrators and a slick app. It sells one line of insurance, only personal, with low limits, and has no complicated old claims (yet). If your house burns down, you open an app and wait. The company has a low expense ratio, high acquisition costs and a high loss ratio.

- Company B — old Traditional Insurance Co. uses a mix of direct sales, captive agents and independent agents. Claims are handled mostly by agents and in-house staff. If your house burns down, your agent turns up with a reservation for a nearby hotel, billed directly to the insurer. The company sells 12 lines of insurance, including small commercial, and a wide range of products within each line, with bundling encouraged. The company has a high expense ratio, high acquisition costs, strong customer loyalty and losses less than the industry average.

A “vanity measure” could easily make one of these companies look better than the other.

The start-up, for example, may claim performance several times better than the incumbent on a “policy per human” KPI,

considering in the count of “humans” agents and brokers. Why does a policy-per-human number matter at all? And why is more policies per human better than fewer?

See also: Insurtech: Mo’ Premiums, Mo’ Losses

Company A and Company B are two different business models, with two opposite approaches about humans -- neither of which is necessarily better. Steve Anderson and I wrote a

heartfelt defense of the model based on agents, brokers and other distribution partners a few months ago.

To measure efficiency, I prefer to use the two traditional components of the expense ratio:

- General operating expense ratio = general operating expenses ÷ earned premiums

- Acquisition ratio = total acquisition expenses divided by the earned premiums (for high growth companies, it’s acceptable to do the division by written premium). This metric includes advertising, other marketing expenses, commissions and other distribution expenses. However, this number (like CAC) can be difficult to compare - for example, are fixed marketing expenses included or excluded? And the economics of customer loyalty are different between direct (where initial CAC is high but renewal is low) and agent sales (where initial CAC is lower and variable but renewal commissions are significant).

*****

I love numbers and – as shared in an interview with Carrier Management - the absence of quantitative elements in self-promoting website articles, conference keynotes, whitepapers and social media exchanges have been one of the reasons for starting the publication of articles about the full stack U.S. insurtech start-ups.

Although I’m sometimes described as “critic” or “cynic” about insurtech companies, I’m only critical of the misuse of numbers and am a big fan of those who get the old school insurance KPI right. I’d love to see innovation succeed in the insurance sector, and I wish all the best to these three players and their investors. Skeptics point out that a quarter doesn’t mean much, that there’s a long way to go before reaching sustainability and that each additional point of loss gets harder to take out. True, but the increased focus this year on reducing losses and increasing prices is making a difference.

Here are the quarterly results:

Skeptics point out that a quarter doesn’t mean much, that there’s a long way to go before reaching sustainability and that each additional point of loss gets harder to take out. True, but the increased focus this year on reducing losses and increasing prices is making a difference.

Here are the quarterly results:

I think – as already mentioned in the previous articles - these companies have strong management teams who could ultimately create valuable businesses. This will take several years, but all three companies are well-funded, even if the combination of statutory capital injections and operating losses consumes tens of millions in capital each year. (The Uber/Lyft model of growing rapidly while also incurring large losses is doubly penalized in insurance because carriers have to maintain statutory capital that increases with premium.)

Here is a year-over-year comparison.

I think – as already mentioned in the previous articles - these companies have strong management teams who could ultimately create valuable businesses. This will take several years, but all three companies are well-funded, even if the combination of statutory capital injections and operating losses consumes tens of millions in capital each year. (The Uber/Lyft model of growing rapidly while also incurring large losses is doubly penalized in insurance because carriers have to maintain statutory capital that increases with premium.)

Here is a year-over-year comparison.

The three companies have sold in the last 12 months between $40 million and $110 million, less than some of the early 2017 enthusiastic forecasts that Lemonade (for example) would hit $90 million of premiums by the end of 2017. In auto, I pointed out at my IoT Insurance Observatory plenary sessions that the pay-as-you-drive telematics approach seems to attract only the niche of customers that rarely use cars – maybe a growing niche, but not a billion-dollar business (in premium at least).

See also: 9 Pitfalls to Avoid in Setting 2019 KPIs

Loss Ratios

Loss ratios have all been below 100%, which is a great improvement from the 2017 performances. The quarterly dynamics show a positive trend, but these loss ratio levels are far from the U.S. market average for home insurance (Lemonade) and auto insurance (Root and Metromile).

While loss ratio is a fundamental insurance number – claims divided by premiums -- I've been asked how to normalize/adjust the loss ratio of a fast-growing insurtech company.

Imagine a fast-growing insurer with the following annual figures:

The three companies have sold in the last 12 months between $40 million and $110 million, less than some of the early 2017 enthusiastic forecasts that Lemonade (for example) would hit $90 million of premiums by the end of 2017. In auto, I pointed out at my IoT Insurance Observatory plenary sessions that the pay-as-you-drive telematics approach seems to attract only the niche of customers that rarely use cars – maybe a growing niche, but not a billion-dollar business (in premium at least).

See also: 9 Pitfalls to Avoid in Setting 2019 KPIs

Loss Ratios

Loss ratios have all been below 100%, which is a great improvement from the 2017 performances. The quarterly dynamics show a positive trend, but these loss ratio levels are far from the U.S. market average for home insurance (Lemonade) and auto insurance (Root and Metromile).

While loss ratio is a fundamental insurance number – claims divided by premiums -- I've been asked how to normalize/adjust the loss ratio of a fast-growing insurtech company.

Imagine a fast-growing insurer with the following annual figures:

To measure efficiency, I prefer to use the two traditional components of the expense ratio:

To measure efficiency, I prefer to use the two traditional components of the expense ratio: