In my past several IIS innovation research articles, I challenged insurers to think big, really big, about how they might innovate with purpose to change the world—and, in doing so, drive tremendous growth. In this article, I address the flipside of that challenge: how to hone too many potentially good ideas into a manageable yet holistic set of innovation investments.

Executives often tell me that their problem is not having too few big ideas, but having too many. Great ideas are purportedly coming at them from every direction. They come from the front lines where the organization interacts with customers and contends with competitors; from technology and marketing wizards keeping a sharp eye on disruptive market trends; from senior executives and board members grappling with issues at the organization’s strategic horizon; and sometimes even from conversations with outside advisers like me.

Peter Drucker offered some of the best advice on how to handle so many potentially great (and possibly awful) ideas:

“Don’t subscribe to romantic theories of innovation that depend on ‘flashes of genius.’ Innovation begins with the analysis of opportunities. The search has to be organized and must be done on a regular, systematic basis.”

In the spirit of Drucker’s advice, here’s a four-step plan insurers can use to initiate a systematic process to uncover, screen, and scale the best ideas using an innovation portfolio approach.

Stimulate and Inventory Opportunities

Start by casting a wide net in the context of your company’s environment, purpose, strategy and capabilities. For example, hold scenario-planning sessions with senior executives and board members to explore continuous and disruptive opportunities and challenges that arise out of key strategic questions. Organize learning workshops to educate and gain insight from the wider organization about potential future scenarios. Engage teams at multiple levels to articulate both desirable and dangerous future histories for the organization. Sponsor innovation contests to uncover both continuous and disruptive ideas.

Continuous innovations offer incremental or faster, better and cheaper-type optimizations, such as shedding costs, reducing cycle times and generating incremental revenue. With sufficient license, numerous continuous innovation ideas can flow out of such discussions. Make sure you capture them.

Disruptive innovations rise to the level of game-changing and world-changing potential. It’s important to create space for these really big ideas. For example, stimulate potential organizational responses to thought questions like these:

- What are the most pressing protection gaps in the communities your company currently serves?

- How might those gaps evolve over the next several decades, especially for those who are the most underserved?

- What evolving technological capabilities might help narrow those gaps, especially as they continue to progress following the Laws of Zero?

- How might you apply these leading edge tools to better expose, model and mitigate meaningful slices of corresponding risks?

- What early lessons from innovators and early adopters around the world might be adapted to your community’s evolving challenges?

- What extreme competitive threats (that is, doomsday scenarios) might new entrants wielding these disruptive solutions pose to your business?

Categorize Opportunities Based on Investment Type and Impact

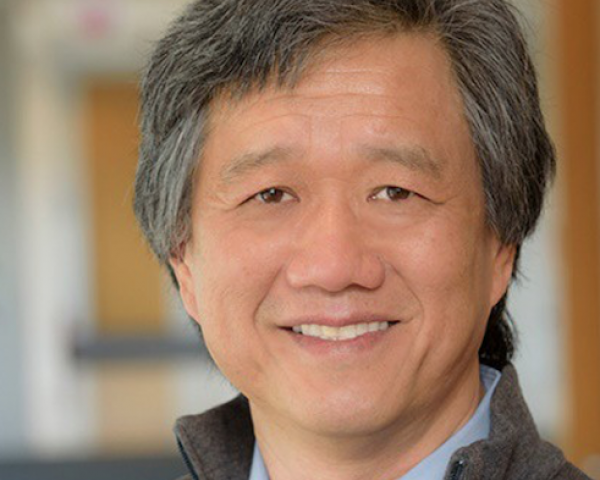

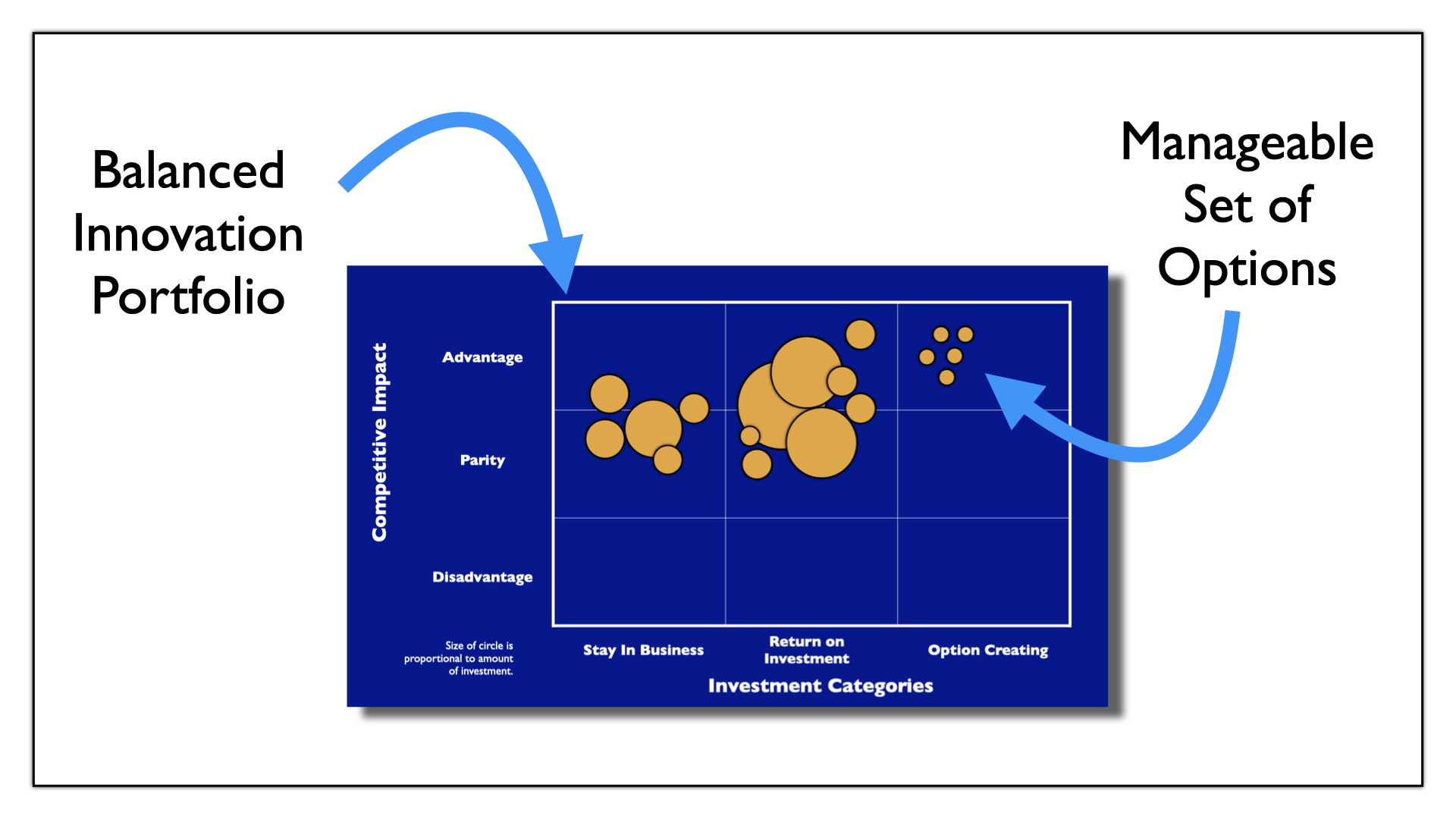

Next, categorize the opportunities according to investment type and a potential competitive impact. This will allow you to array all the ideas in the 3x3 matrix formed by the two categories, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Categorize Ideas Along Two Key Dimensions

Each idea can be categorized as one of three distinct types of investments:

- Stay in business (SIB) investments

- Return on investment (ROI) opportunities

- Option-creating investments (OCIs)

Categorization enables more suitable metrics and better comparative analysis. It also allows for strategic allocation of investment resources across categories based on organizational need.

SIB investments are for basic infrastructure or nondiscretionary requirements. They are common across companies. For example, large investors and regulators are promulgating a range of industry-standard Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG)-related reporting and compliance requirements that most companies will have to follow. The rise in cybersecurity challenges requires significant infrastructure enhancements. COVID-19 has driven significant investments to reconfigure built environments and enable remote work, where possible. SIB investments should be assessed on how adequately they meet regulatory or technical requirements while minimizing risk and cost.

ROI opportunities are company-specific offerings that are pursued for near-term financial returns. Most continuous innovation ideas fall within this category. Standard measures, such as net present value (NPV), return on equity (ROE) or other well-understood metrics are applicable for evaluating ROI opportunities.

OCIs are the earliest stage of innovation initiatives. Companies typically pursue them to explore business opportunities that might yield large returns in the future. They resemble financial options—from which the name is derived—in that they exhibit high risk and offer tremendously high potential returns but do not commit the organization to exercising the option. OCIs do not yield financial returns directly. Instead, they reduce uncertainties and build capabilities and learnings that could be translated into future ROI opportunities, if appropriate. All discontinuous innovation ideas should start as OCIs.

Next, make a high-level assessment of the idea’s future potential competitive impact.

Consider Wayne Gretsky’s adage about skating to where the puck is going, rather than to where it is. This dimension measures differentiation against what competitors will likely have deployed by the time an idea is launched. Once successfully completed, would the innovation have an advantage, be at parity or be at a disadvantage against the competition?

This method addresses two key screening mistakes. The first is evaluating an innovation idea against the organization’s current internal capabilities or product offerings, rather than the alternatives that customers will have in the market. The second mistake is evaluating the idea against current competitive offerings, rather than recognizing that competitors won’t stand still, either.

See also: When Incumbents Downplay Disruption...

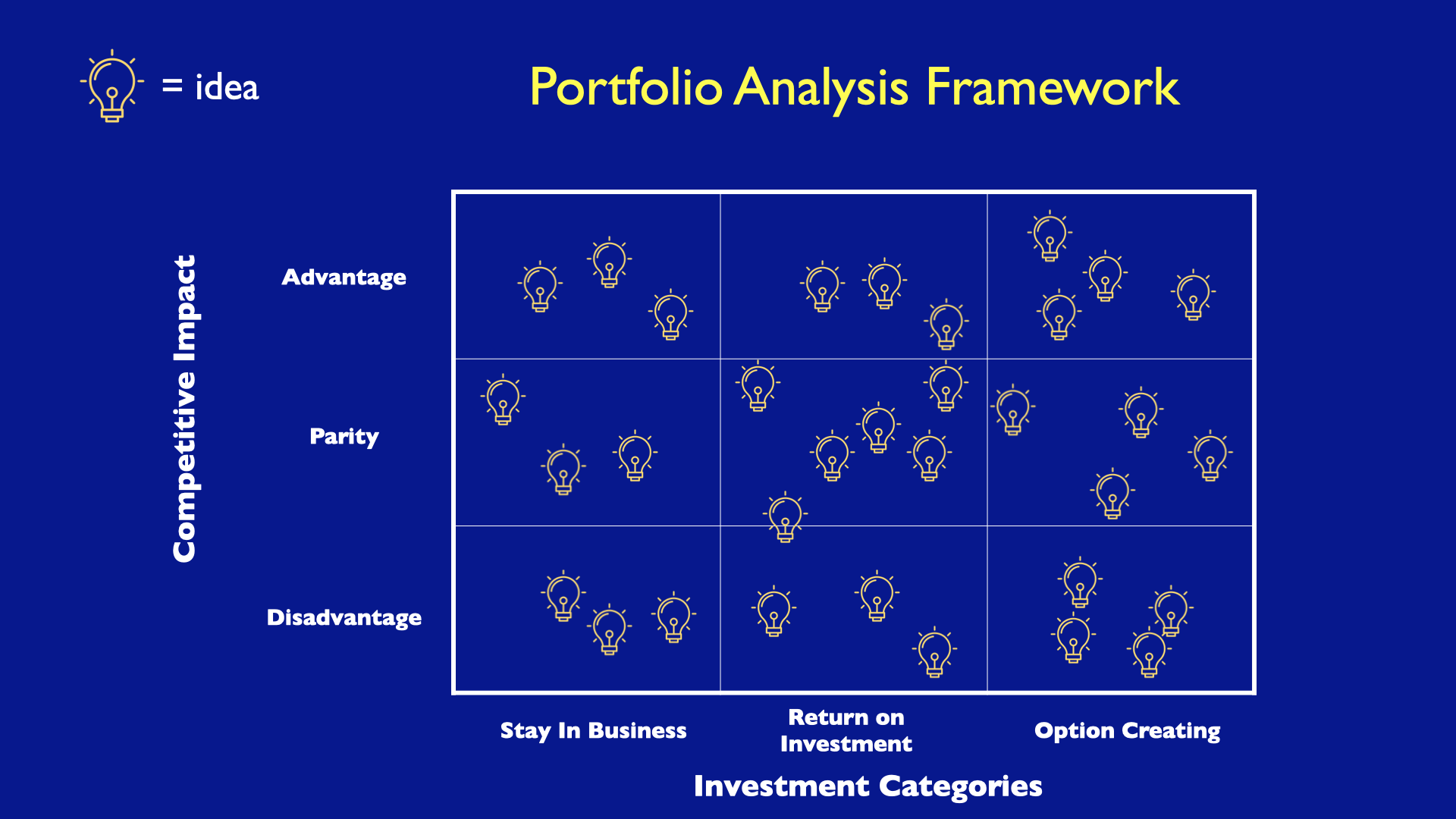

Screen the Opportunities

Arraying opportunities in this analysis framework allows for simple heuristics to eliminate seemingly good ideas that fall outside of acceptable boundaries. For example, companies should not pursue opportunities that, once completed, are already at a disadvantage against the competition—no matter how much they improve upon current internal capabilities. There’s no reason to pursue OCIs that, no matter how advanced they are, would deliver only competitive parity, as new parity offerings would be unlikely to dislodge existing offerings or deliver outsized returns. Figure 2 illustrates how the analysis might look at the end of this stage.

Figure 2: Initial Screening

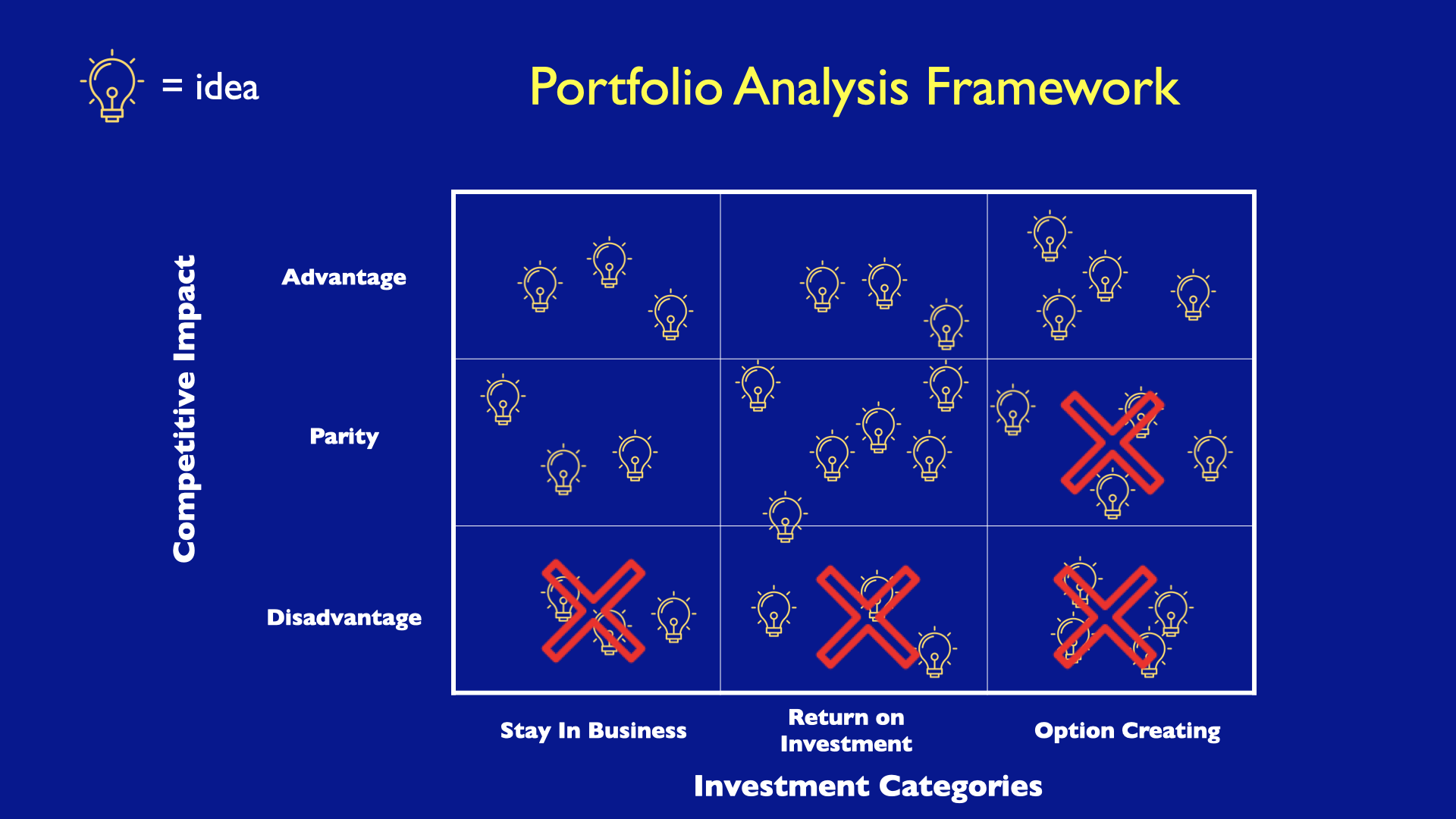

For the remaining opportunities, develop an initial sizing of investment levels and potential benefits according to each investment category. This allows for another level of screening, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Additional Screening Based on High-Level Sizing

For example, eliminate ROI opportunities that do not meet standard corporate hurdle rates. Eliminate OCI opportunities that do not exhibit extraordinary option value or require relatively significant upfront investments. Eliminate SIB ideas that do not adequately minimize cost and risk—be very skeptical of SIB opportunities justified by predicted ROI or OCI benefits.

Rebalance the Innovation Portfolio

No new set of innovation initiatives, no matter how potentially great, can be considered in isolation from continuing innovation programs. The final step of the screening process is to evaluate both existing and potential initiatives in the context of the overall innovation portfolio, and to rebalance that portfolio as appropriate.

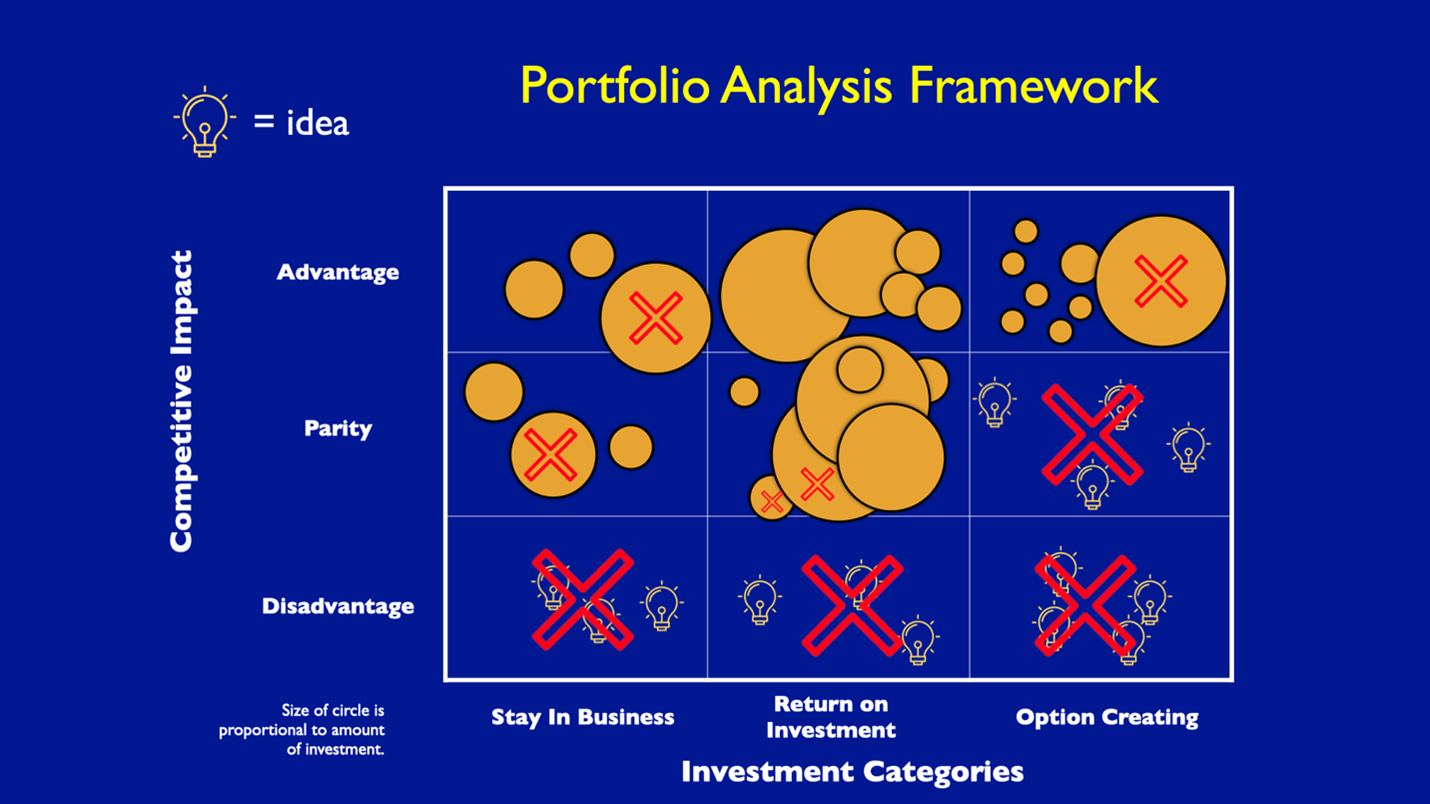

The right prioritization and allocation across the portfolio depends on a company’s investment capabilities, competitive circumstances and strategic aspirations. For example, as shown in Figure 4, a market leader could gear its portfolio toward aggressive growth by enhancing its infrastructure, investing heavily in near-term profitable opportunities and developing a small number of disruptive options for furthering its competitive advantage.

Figure 4: A Market Leader’s Balanced Portfolio

In my experience, the right number of disruptive options is on the low end of the magic seven, plus or minus two. That’s because the limiting factor is senior executive attention, not investment dollars. Market leaders have a lot of money to invest, but no project with truly disruptive innovation can succeed without significant senior executive attention. At the same time, astute companies will not place “all their eggs in one basket” by having only one or two future-looking disruptive options. Instead, they hedge their bets by having multiple bets in place.

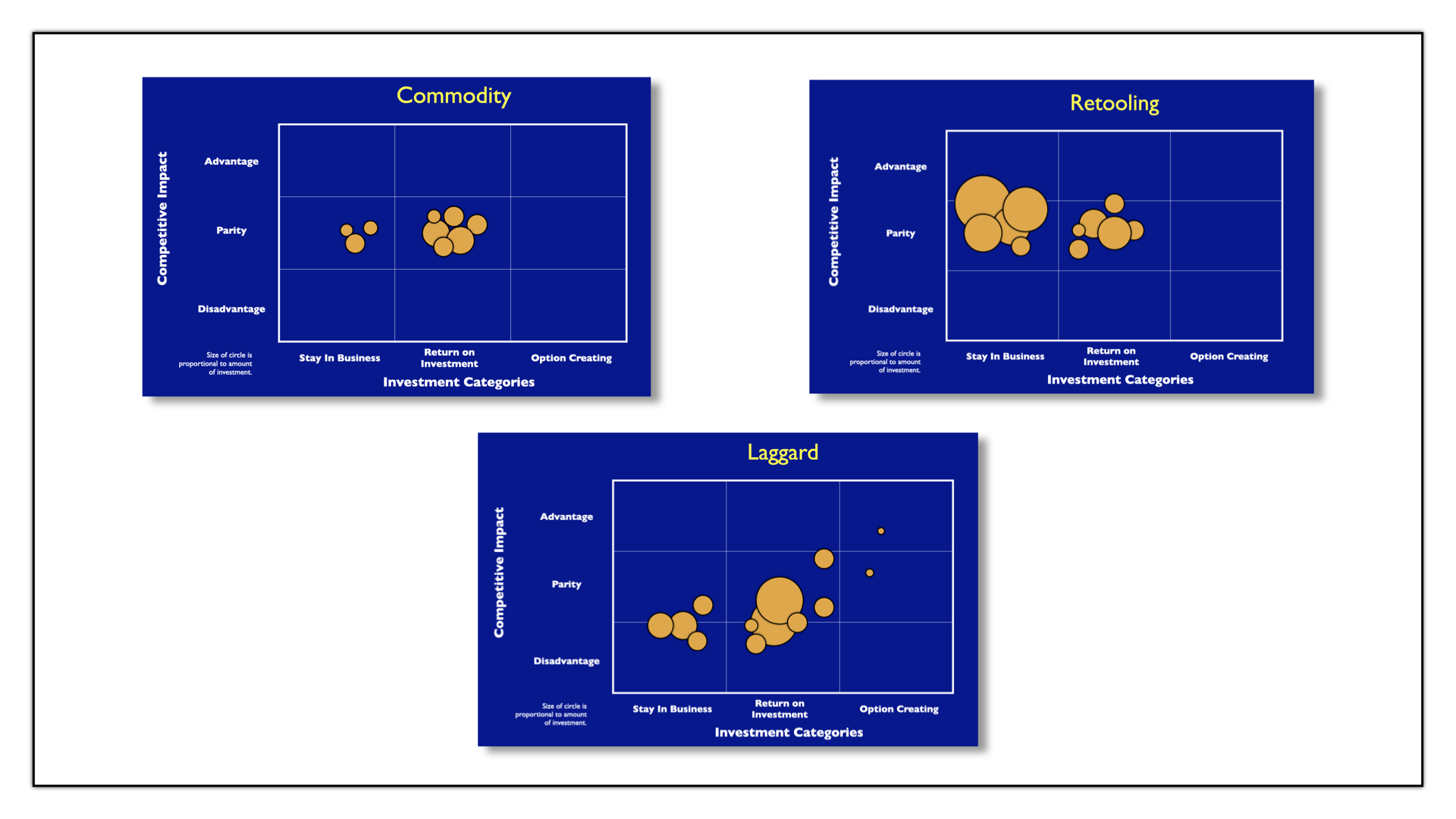

Other illustrative portfolio profiles are shown in Figure 5. Commodity businesses tend to minimize SIB investments and OCIs. Companies that are retooling might emphasize infrastructure and near-term investments and only minimally invest in future options. Underperforming companies tend to invest in programs that barely achieve competitive parity or worse and do little to prepare for the future in any of the three investment categories.

Figure 5: Other Illustrative Portfolio Profiles

***

At the end of this four-step process, companies should have a prioritized and staged investment plan that represents a coordinated enterprise innovation strategy and follows a think-big, start–small, learn-fast innovation roadmap.

Achieving an adequate understanding of the entire landscape of possibilities facilitates and encourages thinking big. Management of the innovation portfolio provides clear criteria for evaluating other big ideas as they come up. It also demands the discipline of starting small and learning fast in the pursuit of disruptive innovations that will shape the company’s future history.